Biographical texts about Vincent van Gogh tend to stress the relationship between Vincent and his brother, Theo. Their correspondence, which Theo kept filed in a large armoire, details the highs and lows of their relationship—and, more broadly, illuminates a very deep familial bond. The loving salutations and valedictions that bookended their letters—“my dear Theo,” “your loving brother, Vincent,”—have often been quoted as evidence of a seemingly singular attachment. Although their relationship has been rightfully emphasized, their brotherly bond has overshadowed the fact that Vincent also had three sisters and another brother. His sisters, like Theo, shaped his worldview, were important correspondents, and, like all siblings, were sources of tension for the artist.

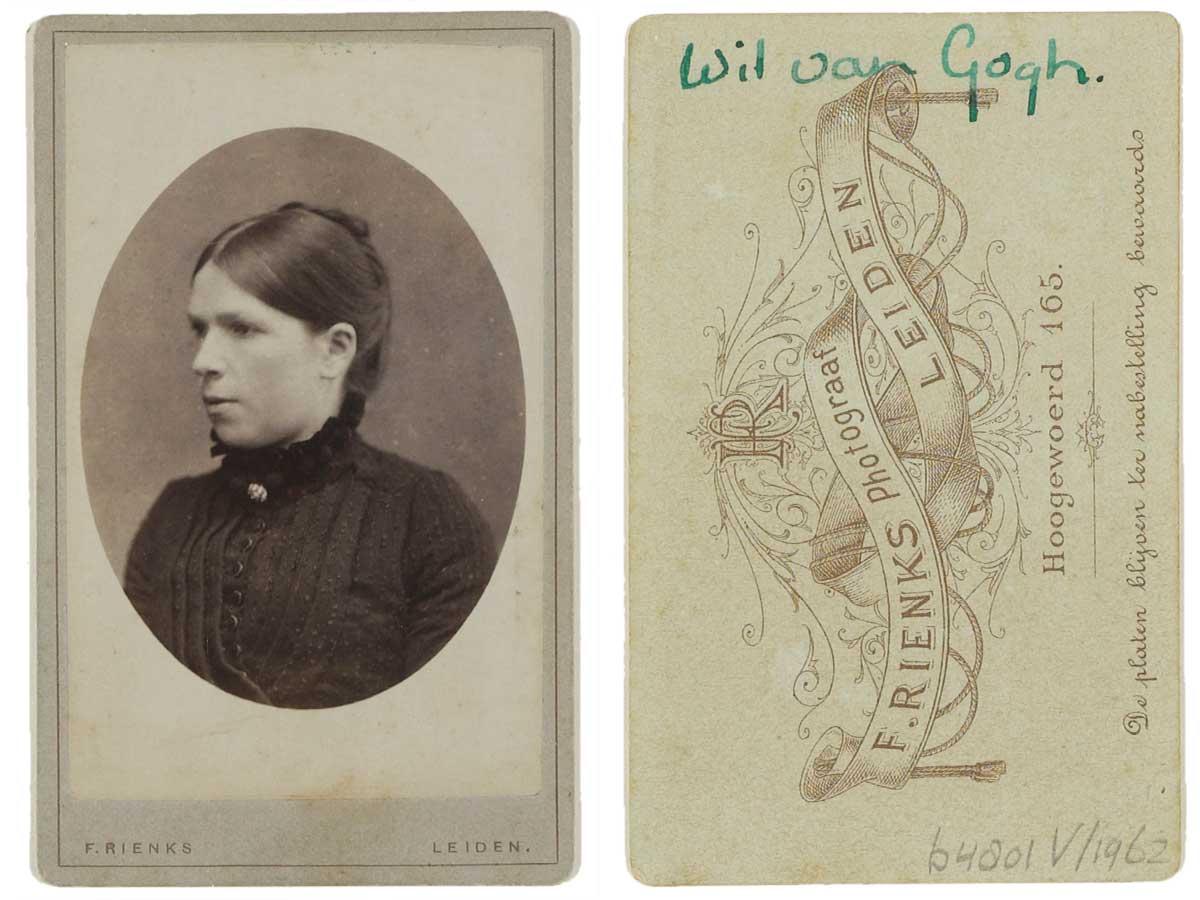

Long overlooked, the sisters—Anna, Elisabeth (Lies), and Willemien (Wil)—are now the subjects of a book, The Van Gogh Sisters by Van Gogh scholar Willem-Jan Verlinden. “You lift one thing, and then other things come up,” explains Verlinden over Zoom. Verlinden first began looking into the sisters when he was researching his 2013 book focused on Van Gogh’s London years. “I said to myself, ‘if the sisters are only half as well documented as Vincent is, then there should be a book in there,’” he recalls. Verlinden decided to spend six weeks investigating the sisters, which turned into three, then four years. “That was the book,” he says, “You have all different possibilities, following different lines, but what I'd wanted to do is tell the unknown story and by doing so, paint the larger picture of the family.”

As was Verlinden’s ambition, The Van Gogh Sisters traces the lives of the different Van Gogh children, set within the larger familial dynamics and against the backdrop of a changing nineteenth-century Europe. Rather than focusing on the siblings individually, Verlinden demonstrates the ways in which their lives were entwined. The siblings, in addition to supporting and living with each other at home and abroad, also saw themselves in relation to each other. While Lies was away at boarding school, she wrote in a letter, “we are all so of one mind, except perhaps for Vincent.”

For context, Dorus van Gogh, Vincent’s father, was a minister and like his wife, Anna (later called Moe) came from an upper-middle-class family. As his employment changed, the family was relocated to parsonages throughout the Netherlands—and a persistent issue was the perception of the family to the villages where they lived. Verlinden highlights that Vincent loved his father and “actually wanted to be the father. That couldn't be. And that's one of the main questions in this whole story.” One of the central sibling conflicts was about who hewed to the norm and who strayed—and the burdens placed on the family by those who forged their own paths.