Kerry James Marshall, Many Mansions, 1994.

Founded in 1879, the Art Institute of Chicago is one of the world’s largest and oldest art museums. Located in Chicago’s Grant Park, the museum houses the works of some of the nation’s most prominent artists, such as Georgia O’Keeffe (1887-1986) and Archibald Motley (1891-1981). The museum’s collection also includes the works of many stalwarts of the Western canon beyond the U.S. such as Édouard Manet (1832-1883), Vincent van Gogh (1853-1890), and Pablo Picasso (1881-1973).

Comprising roughly 300,000 works, the museum's collection spans contemporary painting and sculpture to Ancient Egyptian artifacts. Established as a research institution, the Art Institute of Chicago not only holds five conservation laboratories but is also home to the revered Ryerson and Burnham Libraries, one of the largest art history and architecture research libraries in the nation. Ranked among the top 20 most visited museums in the United States in 2022 by The Art Newspaper's annual survey of museum attendance (and 51st globally), the Institute welcomes over one million visitors annually.

Kerry James Marshall (1955 - ) is known for his large-scale paintings, and sculptures that explore African-American culture and history. Many Mansions (1994) is the first in his series of five works called Garden Project, which depict housing projects in Chicago and Los Angeles, in this case Stateway Gardens. “They look like everything else but a garden….” Marshall has said about the contradictions inherent in these settings. “Was there a trend once to name housing projects as garden spots? Isn’t there an irony there?”

In this work, Marshall juxtaposes the bright colors and artificially joyful manicured trees with the forlorn weathered signage and ebony-skinned figures who are planting a garden, emphasizing the contrast between utopian ideals and actual jarring reality.

Born in Birmingham, Alabama, Marshall moved with his family to Los Angeles when he was eight years old. There, they lived in a housing project called Nickerson Gardens. His upbringing in the Watts neighborhood of Los Angeles had a huge impact on his work. About this influence, he has said, ‘You can’t be born in Birmingham, Alabama, in 1955, and grow up in South Central [Los Angeles] near the Black Panthers headquarters, and not feel like you’ve got some kind of social responsibility.”

Symbolizing the mysticism of Catholicism, the religion under which artist Katharina Fritsch (1956-) was raised, Monk (Mönch), Fritsch's work from 1997-1999, is a dark ashen figure with his eyes closed as if in meditation.

Monk is one in a series of three figures by Fritsch that represent the apocalypse, the other two being a white skeletal doctor and a menacing red art dealer. Each of these life-size sculptures acts as a modern interpretation of the Knight, Death, and the Devil from Albrecht Dürer’s 1513 engraving of the same name.

Fritsch has been creating such lifelike mythical figures since the early 1980s. Cast in polyester, Monk represents the artist’s fascination with the mysteries of Medieval Europe, as well as German culture and folklore.

The Girl by the Window (1893) by Edvard Munch (1863-1944) is, according to the Art Institute of Chicago, representative of the artist’s experimentation with Impressionism and Symbolism. This work is, however, truer to Munch’s Norwegian roots since it embraces the Romanticism of Northern European art in the late nineteenth century.

Created the same year as Munch's most well-known work, The Scream, The Girl by the Window follows themes of anxiety and sadness arguably often represented in Munch’s use of color and subject matter; the girl, in this work, is separated from the outside world by the physical barrier of the window. Munch’s use of color underscore these themes in this work, with the violets and blues further communicating feelings of isolation and melancholy.

The Awakening of the Forest (1939) stands as an example of the fantastical childhood realm that Paul Delvaux (1897-1994) often explored in his work. The Awakening of the Forest is one of the most prominent works Delvaux created after embracing Surrealism; the piece transforms a passage from Jules Verne’s novel Journey to the Center of the Earth (1864) where two of the main characters, Professor Otto Lidenbrock and his nephew Axel, shown on the far left of the composition, wander into a prehistoric forest that lies deep within the earth. In the forest, under a full moon, are a phalanx of nude women entranced in an automaton-like state. The painting also features two women in Victorian dress. Beyond the apparent observations, the piece holds very little further context, which adds to its mystery.

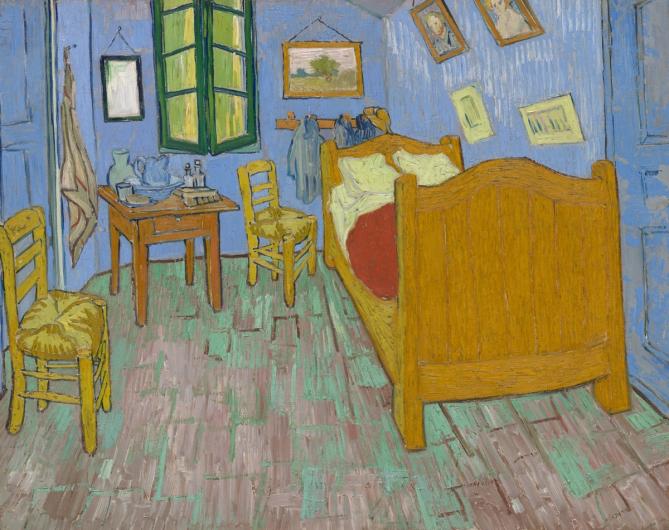

The Bedroom (1889) by Vincent van Gogh (1853-1890) is one of three paintings of the artist’s bedroom. The first of these bedroom works was painted shortly after he moved into his house in Arles, France in 1888, inspiring the artist to fervently decorate and furnish his first home. The artist painted many canvases to fill up his blank walls. He painted so many that he became exhausted and spent over two days in bed recovering. This recovery period inspired the first Bedroom, which van Gogh described to his brother in a letter as an expression of relaxation in the clashing vibrant colors, which to the viewer, have the opposite effect of communicating stress and anxiety.

Venus de Milo with Drawers (1936) by Salvador Dalí is a half-size rendition of the ancient Greek sculpture of the goddess, Venus de Milo (130-120 BC). Somewhat in line with the concept of the readymade, popularized by Marcel Duchamp (1887-1968), this sculpture is “completely useless” in the words of Dalí.

Readymades consisted of existing materials and objects, usually mass-produced, that were then ascribed new meanings in the context of the ideas that were imposed upon them by the artist. Of readymades, Dalí stated that they were a great way of revolutionizing consciousness by affixing fantastical and even fetishized ideas onto something meaningless. Venus de Milo with Drawers specifically acts as a reflection of Dalí’s sexual subconscious, with the cabinet on the figure of a woman acting as an “anthropomorphic cabinet”. Considering this, the sculpture further represents Dalí’s exploration into the psychology of sex and desire, supported by the Ancient Roman goddess of love.

Weaving (1936) by Diego Rivera (1886-1957) features Luz Jiménez, master weaver, Indigenous artist, and cultural historian of the Nahua, Mexico’s largest Indigenous community. Weaving follows a theme of celebrating Mexican national identity by honoring the country's Indigenous communities and folk cultures rather than celebrating a whitewashed colonized version. Weaving captures Jiménez in practice of a traditional weaving technique taught to her by her mother, celebrating Nahua customs and practices. At the same time, the piece acts as a quiet rebellion against colonial Spanish culture in Mexico. Alongside Rivera, Jiménez was an active figure in the Mexican Revolution and became an Indigenous Mexican cultural icon.

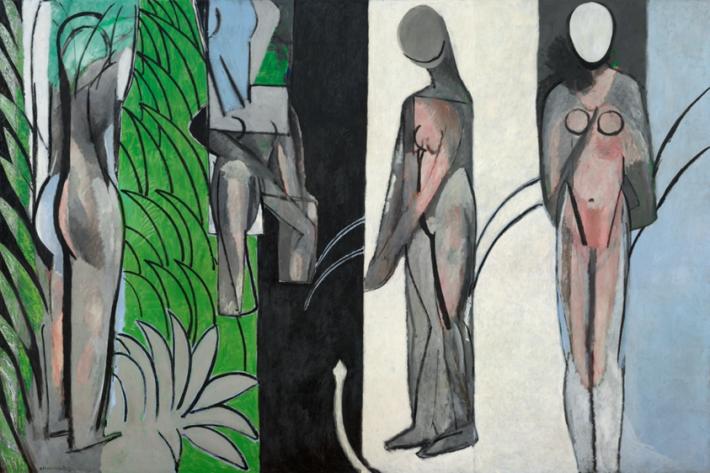

Bathers by a River (1909-1917) marks the stylistic evolution of French painter Henri Matisse (1869-1954). Among a series of three works that Matisse was commissioned to paint for Russian art collector Sergei Shchukin, who later rejected the work, and only accepted its two counterparts. Originally, it depicted a realistic pastoral scene, which Matisse transformed into a masterpiece of Cubism. Matisse took his original figures and altered their proportions, making them oval and faceless. The painting continued changing as Matisse altered it over the years, dividing the composition into four distinct sections and changing elements such as a blue river into a thick, black vertical line. The piece is intended to depict the war-torn state of Europe during WWI.

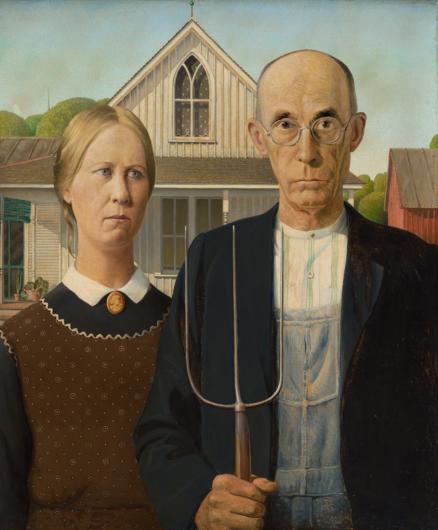

American Gothic (1930) depicts a return to tradition as painted by Grant Wood (1891-1942). The piece, which has been widely interpreted as a satire of Midwestern Americans and their outdated culture and ideals, is intended to depict a return to the simplicity of older generations, communicating wisdom during the Great Depression. During the Depression, Wood saw reassurance in the ideals and lifestyle of rural Americans and their self-sufficient lifestyle. Despite this misconception, American Gothic stands as one of the twentieth century’s most iconic paintings. Depicting a father and his daughter, both dressed in outdated clothing and posed awkwardly, the painting mimics tintype family photographs of the mid-to-late nineteenth century.

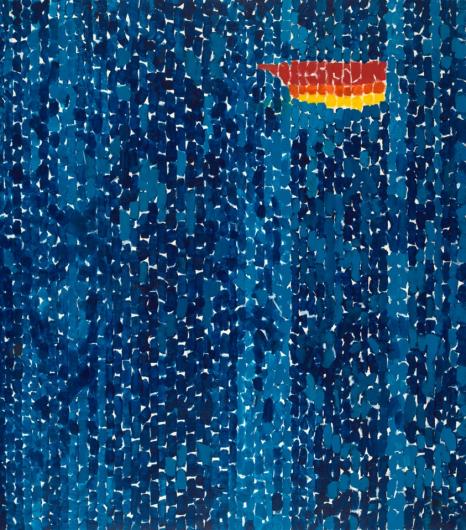

Alma Thomas (1891-1978) transitioned from a representational painter to a lover of abstraction in the 1970s, with most of her work, such as Starry Night and the Astronauts (1972), featuring mosaic-like natural scenes. Inspired by the appearance of the world from the window of an airplane, having a bird’s eye view changed how Thomas approached color and form. Starry Night and the Astronauts features a wide and expansive view of the night sky and our solar system’s celestial bodies, despite the ability for it to also look like reflections in a body of water. Thomas’ process leaves the piece almost backlit by slivers of blank canvas, reflecting her unique relationship with color and light. “Color is life, and light is the mother of color," Thomas wrote. Thomas was the first Black woman to have a solo exhibition at the Whitney Museum of American Art. The show was in 1972 when the artist was 81.

Effie Jackson

Effie Jackson is a contributing writer for Art & Object and graduated from UNC Asheville with a BA in Art History, where she received the University Research Scholar award in recognition for her undergraduate thesis. She is currently pursuing her MBA at Meredith College in preparation for a career in gallery/museum administration. When she is not working or studying, she loves doing yoga and playing with the family pup.