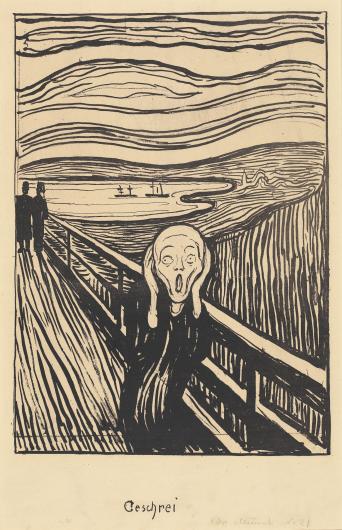

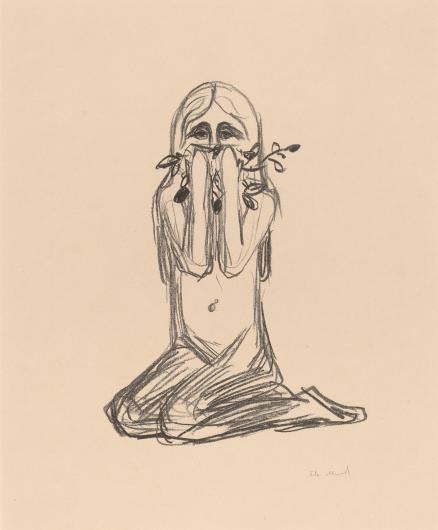

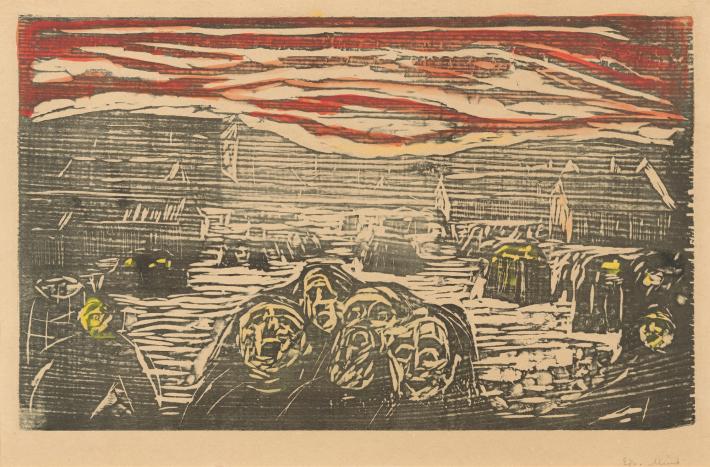

It may not come as a surprise that Edvard Munch (1863–1944), the painter of one of the most iconic paintings in the world, The Scream, lead a troubled life. The powerful image of a twisted figure crying out, set against a tumultuous bright red sky, evokes the depths of human despair, or as Munch described it, the “scream heard through all nature.”

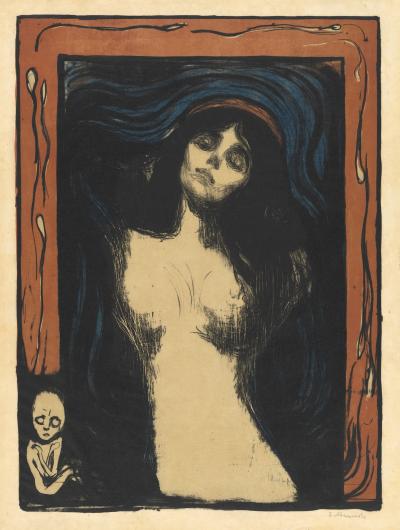

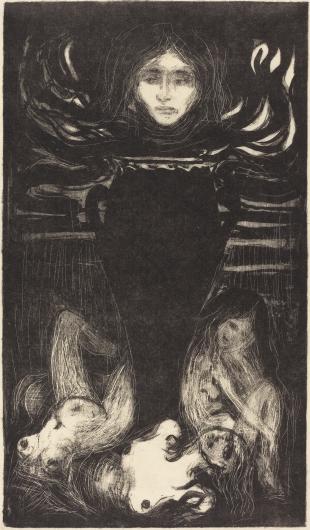

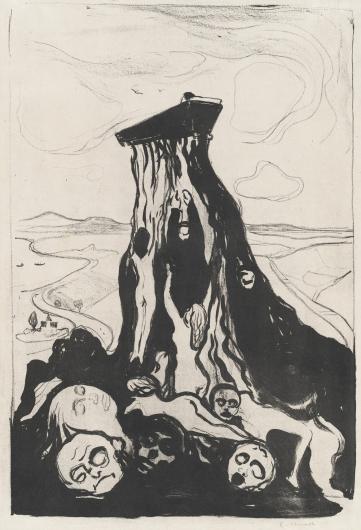

The fact that Munch was able to so beautifully channel a universal feeling of anguish is due to his skill as an artist, and his own experience with grief and mental illness. An exhibition of fifty Munch prints, on view through September 6, 2020, at the Chrysler Museum of Art, Edvard Munch and the Cycle of Life: Prints from the National Gallery of Art, explores how Munch used his art to work through his pain. According to Chrysler Chief Curator Lloyd DeWitt, Ph.D., "The work of the Norwegian artist has come to symbolize the crisis of modern life. The Chrysler’s exhibition is an original concept that focuses on Munch’s career-long obsession with the theme of the cycle of life, from the seeds of love and the passing of love to anxiety and death."