Venus of Willendorf as seen from all four sides. As shown at the Naturhistorisches Museum in Vienna, Austria, in January 2020.

The history of the female nude is complex and profoundly entangled with women’s rights. The subject matter and the manner in which it appears through the ages is sometimes academic, often objectifying, and occasionally empowering.

This list spans approximately 25,000 years of art-making and is by no means comprehensive. Rather, it serves as a highlight reel of particularly fascinating instances in which an artist rendered the female form in a manner that additionally captured some aspect of the concurrent culture. It should also be noted that this list is exclusively focused on Western art history.

Special Note: October is Breast Cancer Awareness Month. Click here for information and resources.

Unknown, Woman of Willendorf, 30,000 - 25,000 BCE.

This sculpture, which is small enough to fit in the palm of one’s hand, is one of the oldest artworks ever recovered. Found in Willendorf, Austria in the early twentieth century, its purpose has long been a source of debate. An initial, popular theory suggested that the statue was prehistoric pornography. Today, it is commonly believed that it is either a fertility token—due to the exaggerated rendering of the figure’s vulva and breasts—or a self-portrait—made as the artist looked down at their own body. This last theory is also supported by the lack of facial features.

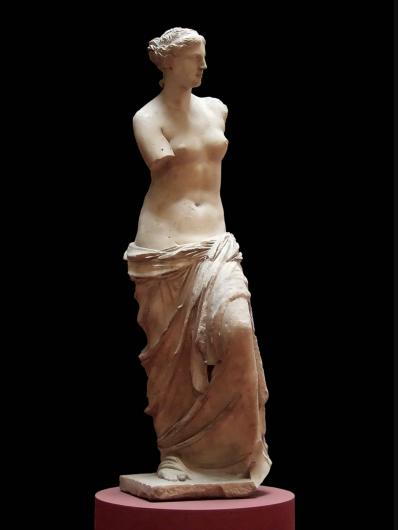

Alexandros of Antioch, Venus de Milo, 130 BC.

The Venus de Milo is characteristic of the Greek understanding of the human body in general rather than of the female form in particular. Still, this sculpture is one of the most famous depictions of the nude body and is therefore a vital piece of this list. Greek artists placed an emphasis on perfection, athleticism, and symmetry. Statues such as this Venus were never based on one specific model. Rather, artists would observe the most so-called perfect aspects of several models and combine them to create the ultimate example of a human figure.

Giorgione (likely completed by Titian), Sleeping Venus, 1510.

For centuries, artists have returned to this pose and composition for inspiration and to create artwork that exists in dialogue with it. Although a 1499 woodcut has been presented as a possible inspiration for this pose, the nude figure's scale and the artist's singular focus on her were unprecedented. The composition has since remained influential. One need only look to Titian’s Venus of Urbino, Manet’s Olympia, Picasso’s Reclining Nude, and countless others.

François Boucher, Jupiter, in the Guise of Diana, and Callisto, 1763.

The story of Jupiter’s seduction of Callisto, achieved while the god was disguised as Diana, has long been used by artists as a sort of excuse to create a scene of sapphic intimacy that could still technically qualify as heterosexual. Additionally—within the context of the female nude—this allowed artists to create a sensual scene featuring two, rather than one, scantily clad women. Boucher, the ultimate Rococo artist, surely delighted in the production of such an artwork.

Elisabeth Louise Vigée Le Brun, Marie Antoinette en Chemise, 1783.

This painting, created by one of only fourteen women admitted to the Académie royale de peinture et de sculpture, is a genius example of an artist’s ability to create a revolutionary statement through art. This portrait of a French queen is unique in its total lack of any reference to the king. Marie Antoinette is presented as an individual, rather than as an asset. Though the Queen may appear dressed to a modern audience, contemporaneous audiences—and the general public in particular—were scandalized by her lack of clothing. These two factors, unfortunately, led to the forced removal of the painting at Vigée Le Brun’s first Salon exhibition.

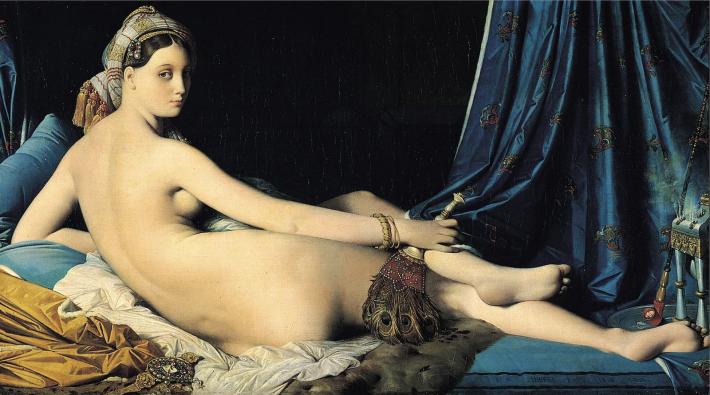

Jean Dominique Ingres, La Grande Odalisque, 1814.

This painting, though beautiful in its own right, dabbles in several deeply problematic traditions including the diminishing, exoticizing, and sexualizing of non-white individuals as well as cultural appropriation. Although the woman’s skin tone and features are heavily Westernized, her body is elongated to manufacture a sense of otherness. She even appears to have extra vertebrae. Lastly, the central figure is surrounded by objects—a fan, a pipe, and so on—that are meant to situate her within a harem and mark the artwork as Orientalist.

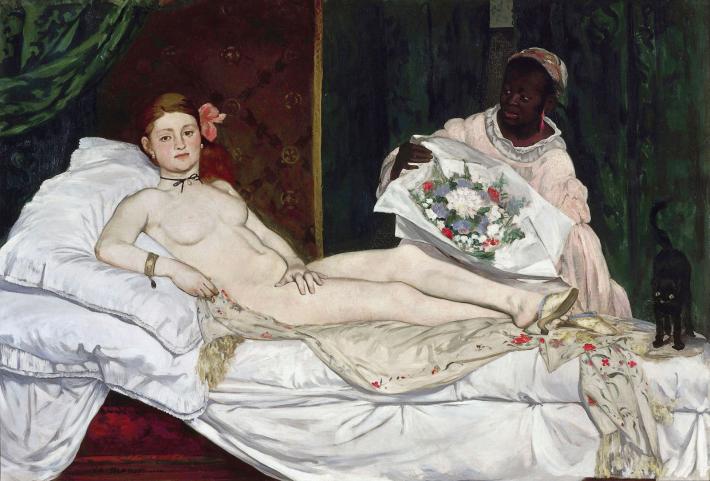

Édouard Manet, Olympia, 1865.

Though the painting's composition was clearly meant to fall into the academic and historical tradition of the reclining, female nude, Édouard Manet also chose to include several details—her jewelry, the flower in her hair, and the cat by her foot—in this painting which identify the central woman as a prostitute. This identity in combination with the subject's so-called confrontational gaze was entirely scandalous to audiences at the time. Today, many academics are more interested in the maid—based on the model Laure—and what her portrayal can tell viewers about racism, beauty, and autonomy.

A photograph of Marilyn Monroe featured in Playboy. Published in 1953. Taken in 1949.

Hollywood starlet Marilyn Monroe—long deemed pop-cultural icon by Andy Warhol and countless others—was also the first Playboy centerfold and the first-ever ‘Sweetheart of the Month,’ a precursory title to the eventual ‘Playmate of the Month.’ It is important to note that the star never agreed to be featured in the magazine. The iconic centerfold image was captured four years before the inaugural edition, when the not-yet-famous Monroe was struggling for cash. Hugh Hefner purchased the centerfold image, taken by Tom Kelley, from the John Baumgarth Calendar Company.

Today

A censored, nude selfie taken by Kardashian and posted to Instagram on March 7, 2016.

Kim Kardashian’s name is synonymous with many pop-culture topics including the selfie. She came into the public consciousness in 2007, when an ex-boyfriend released their sex tape. According to the star, this was done without her consent. Before the release of Selfish, a coffee table book of selfies, Kardashian was hacked by an unknown entity who threatened to release unseen private photos. The star chose to publish the hijacked images in a centerfold series of the book. Though many see Kardashian as an airhead perpetuator of sex-obsession and the objectification of women, one cannot deny the relative autonomy that her nude images possess. For centuries, the most culturally relevant images of the female body were painted, sculpted, and captured by and for men.

Ivy Pratt

Ivy Pratt is a regular contributor to Art & Object.