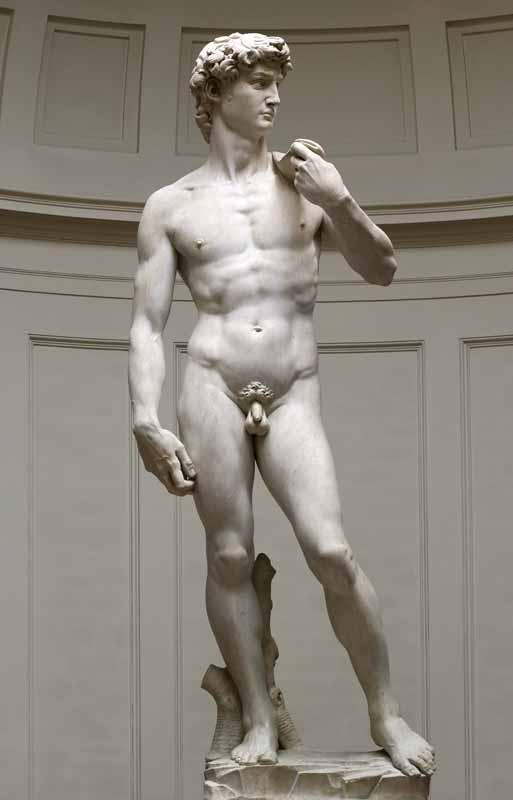

Pioneered by the Greeks in the fifth century BCE, it evolved during the Hellenistic era to include a visible movement in the torso. Michelangelo brought the contrapposto to its zenith, moving the different muscle masses on different axes. His David, while more static than his other nudes, is a famous example of this, and, in all, his work influenced baroque sculptors such as Bernini, who would also include torsion and twist in his nudes.

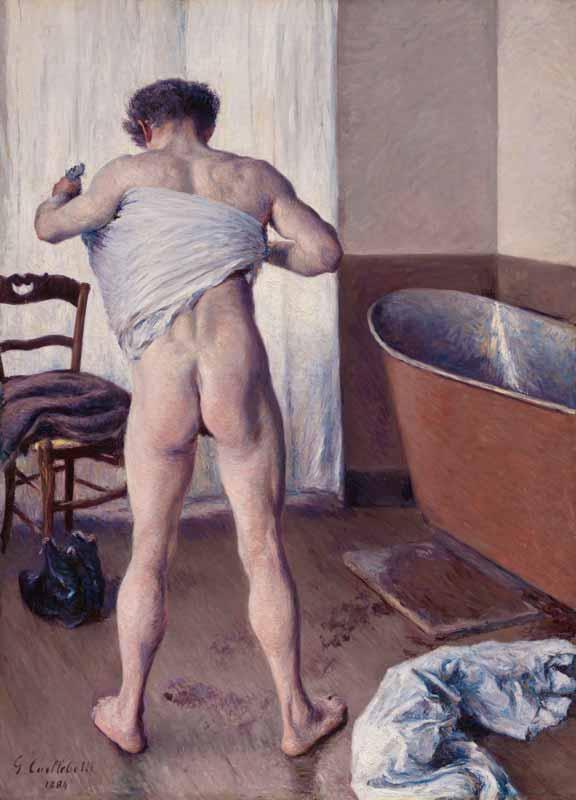

What’s more, from the Renaissance onwards, it is common to see a heroic nude in an “arm akimbo” pose coupled with the bodyweight resting on the opposite leg. This, in Rubin’s words, exemplifies “an enduring iconographic association of the angled elbow with manly vigor, fearless self-possession, and even defiance.” Both of Donatello’s representations of David, the first, in marble, dated 1409-1409 and the second in bronze, dated 1435-40, display this pose, which, coupled with the statues’ distinctive boyish charm, signifies the defiance of David, the Israelites, and the Florentines against their seemingly overpowering tyrants. Benvenuto Cellini’s Apollo and Hyacinth has the god posed with arm akimbo. It was not only the pose of mythological, or biblical heroes, though. It was given to soldiers, prosperous merchants, aristocrats, gentry, and all kinds of gentlemen, whether naked or clothed. “There is a functional aspect to putting hand on hip,” writes Rubin in Seen from Behind: Perspectives on the Male Body and Renaissance Art. “In representation as in reality, it can balance or counterbalance a heavy load.”