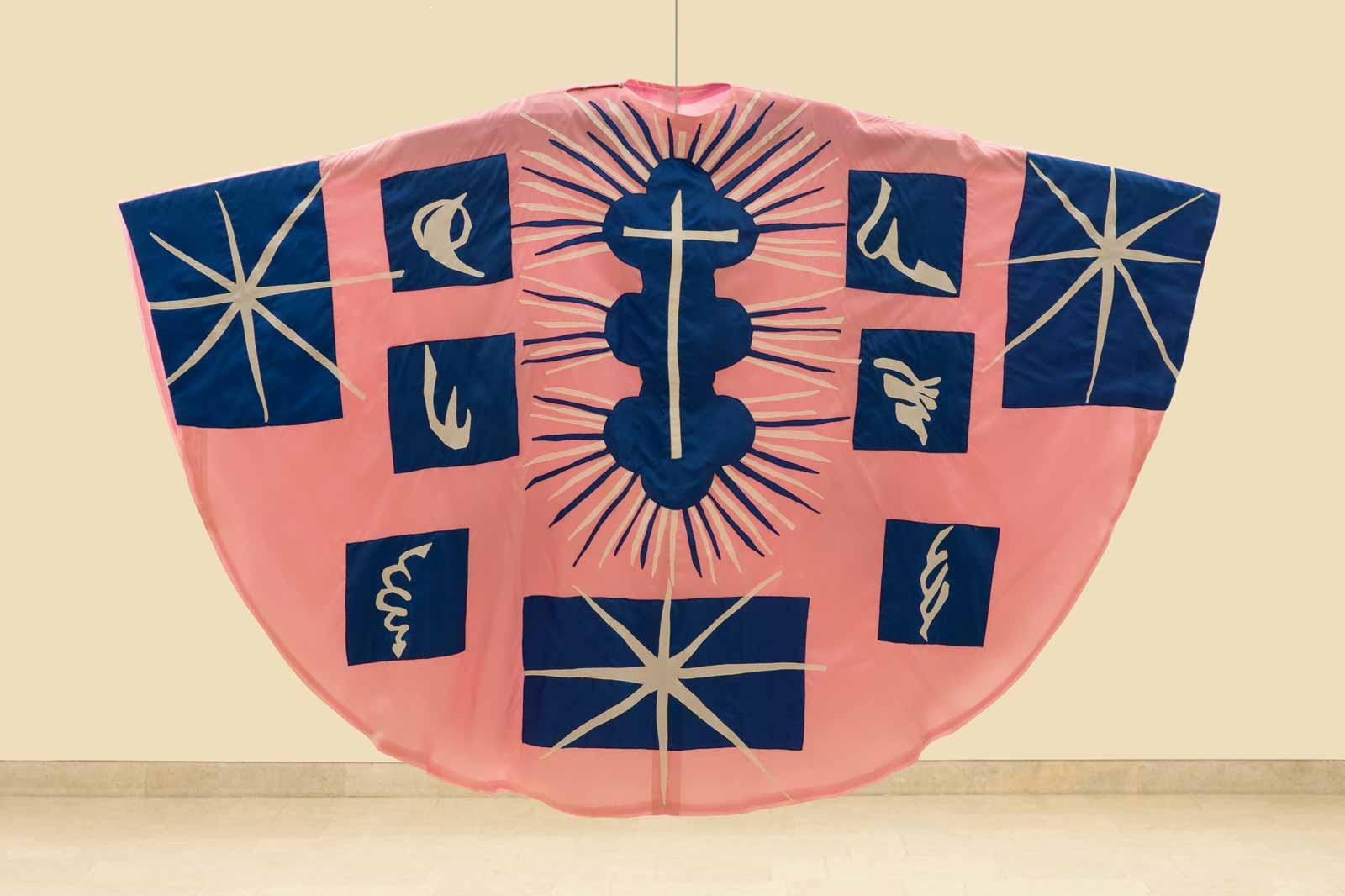

A pink, blue, and white chasuble floats in the middle of the exhibition’s first gallery. Matisse designed several of these vestments for the Our Lady of the Rosary Chapel in Vence, France between 1949 and 1951. The rose chasuble is only used twice in the whole liturgical calendar year, and is associated with joy and expectation during the somber days of Lent and Advent. With its overlapping shapes and vibrant blocks of color, the chasuble is clearly from Matisse’s paper cutting phase, but this time the piece is made of embroidered silk instead of layered paper. While it does contain crosses and a crown of thorns, the chasuble is also graced by starbursts and squiggles that look more botanical than liturgical. Matisse was baptized Catholic, but was ardently atheist as an adult. However, this chasuble and its accompanying chalice veil, maniple, and burse offer ample space for the artist’s playful, cheerful hand.

Henri Matisse, Rose Colored Chasuble, 1951. Embroidered silk. 130 x 200 cm. Col. Chapelle Matisse, Dominicaines, Vence.

During World War II, a nursing student named Monique Bourgeois answered an ad placed by Henri Matisse, who needed assistance after an intestinal cancer surgery. The two became friends, and once he recovered, Matisse made portraits of the young woman in his studio. In 1946, Bourgeois entered a convent, much to the secular painter’s chagrin. Soon after, Matisse began to design a chapel for Bourgeois’s order, the Dominican sisters of Vence. It was Matisse’s last major project, and he considered it his masterpiece. When Bourgeois, now known as Sister Jacques-Marie, asked Matisse if his work was inspired by God, the artist replied, “Yes, but that god is me.”

Closeness to God is at the core of Playing Before God. Art and Liturgy at the Arpad Szenes-Vieira Da Silva Museum in Lisbon. The exhibition features works that Matisse, Maria Helena Vieira da Silva, and Lourdes Castro made for religious spaces, and for use during worship. It’s a rare opportunity to experience these works outside of their respective religious contexts, and seen together, they form a dynamic exploration of light, color, and material. But Playing Before God also raises questions about the status of objects made by artists for the church. Curator Paulo Pires do Vale asks, are these pieces artworks, or something else entirely?

Vieira da Silva, Panel for the sacristy of the Palácio de Santos Chapel, 1983. Oil on wood. 100 x 81 cm. Col. Fundação Arpad Szenes–Vieira da Silva.

Henri Matisse, Rose Colored Chasuble, 1951. Embroidered silk. 130 x 200 cm. Col. Chapelle Matisse, Dominicaines, Vence.

In the second gallery, a projector flips through photographs of the stained glass windows at the Church of Saint-Jacques in Reims, France. The windows were designed in 1966 by Vieira da Silva, a Portuguese abstract painter who, aside from a period of exile in Brazil during World War II, spent the majority of her career in Paris. Though they’re clearly transparent, the windows hold none of the Christian content we might expect to see in a 12th century Gothic church: there’s no storytelling or moralizing, no saints or Stations of the Cross. Instead, Vieira da Silva’s windows are very much like her paintings: full of agitated textures, irregular forms, and stacked segments of grey and red. The artist’s busy rearranging and filtering of light produces an ambiguity and openness akin to the large, dark canvasses of the Rothko Chapel at Houston’s Menil Collection.

Vieira da Silva, Veni Sancte, 1981. Oil on canvas. 105 x 102cm. Col. Comité Arpad Szenes–Vieira da Silva, Paris.

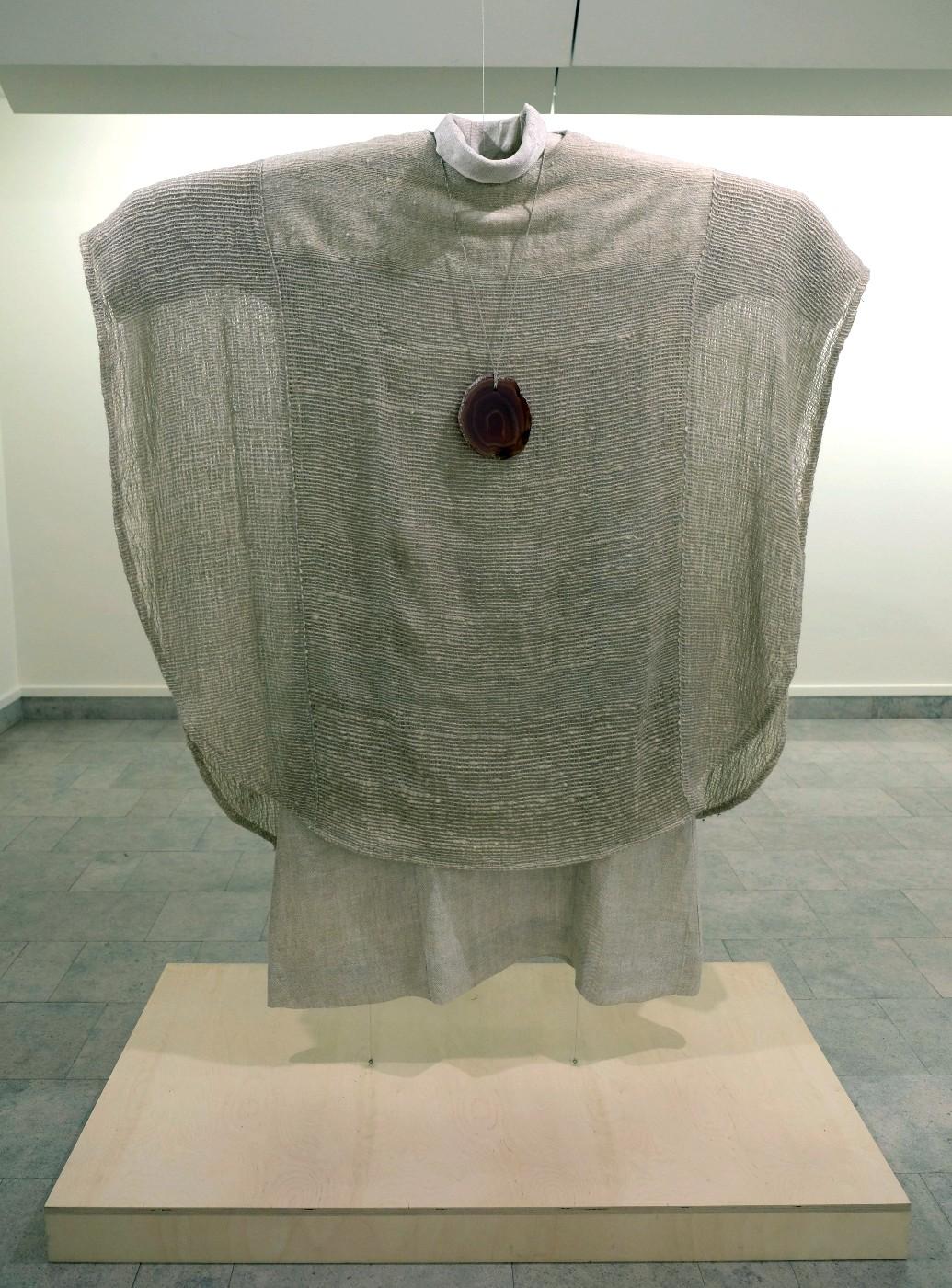

The rest of the exhibition is dedicated to Lourdes Castro, one of Portugal’s most renowned living artists. Here, vestments created by Castro for the Tree of Life Chapel at the Braga Seminary (2012-2015) are on public display for the first time, along with a small model of the church and her preparatory sketches and letters. Made from undyed cotton, linen, silk, and wool, Castro’s earthy chasubles are a striking counterpoint to Matisse’s exuberant, jewel-toned garments. The word chasuble comes from the Latin casula, or “house.” The Greeks and Romans wore the garment to protect against bad weather, but Castro’s vestments are made with a delicate open weave, and are permeable and nearly transparent. In 2015, Castro said, “the spirit, and spirituality is what is called the invisible. The transcendent is the invisible. It attracts me. It helps me a lot.” Castro’s vestments allow the light and spirit in.

Lourdes Castro, Agate disk, chasuble and alb from natural fibers, 2012-2016. Agate, traditional Portuguese 2 thread weaving, linen fibers. Col. Seminário Conciliar de S. Pedro e S. Paulo de Braga

Artists have long been at the service of the church. Some of the most memorable works in Western art history have Christian content. The 20th and 21st centuries present new obstacles to this historic relationship, but the artists in this exhibition form a through-line of successive inspiration that is creative, if not faithful. After all, ‘liturgy’ comes from the Greek words leitos and ergos, meaning ‘public service’ and ‘worship of the gods.’