Also involved in contentious lawsuits was the estate of Robert Indiana (1928-2018), best known for his popular LOVE sculptures (the suit was settled recently), while that of Vito Acconci (1940-2017), in another messy situation, declared bankruptcy after being sued by his landlord of decades for unpaid studio rent. One major issue is that Acconci had compiled an encyclopedic archive of life in the New York avant-garde that he intended to be kept together and housed in his Dumbo studio, but with no artworks approved for sale, there are no funds to maintain the estate. The tale of Scott Burton (1939-1989) was different, but the results were similar. An acclaimed sculptor in great demand at the time of his death from AIDS-related causes, he left his estate to the Museum of Modern Art, its future seemingly assured. That proved not to be the case, primarily because MoMA, as a museum, proved unable to perform the tasks appropriate to an estate, including finding a dealer to foster a market for the artist’s work. As a result, Burton virtually disappeared and is only now being reintroduced to the public by a group of highly motivated curators, artists, and scholars.

Still, there are success stories. The Adolph and Esther Gottlieb Foundation, one of the first artist-endowed foundations, has endured for nearly 50 years, awarding over $22 million in grants to date. When the organization was established in 1976, there were no others like it, and its founders were not at all sure how long they could keep it going. It was structured as a nonprofit to benefit mature artists while preserving Gottlieb’s legacy. Sanford Hirsch, an artist close to the Gottliebs, became its first executive director and has remained in that position, working with Pace Gallery over the years. His advice to artists? Document everything. Make clear plans. Find someone you trust to carry out your wishes. Beyond that, he admits, there’s no easy formula. “I wish there were,” he says.

Saul Ostrow, a critic and curator who has become a sort of legacy whisperer, noted that there is a surge of interest in estates beyond those of celebrated artists. He credits this to the rewriting of the canonical history of Modernism that created a vigorous new market for once-marginalized artists, especially artists of color and women artists. He offers the same advice as Hirsch: write a will, appoint a knowledgeable executor (which often excludes family members), and document the work. Trusts are something Ostrow also recommends. Since no individual person inherits the artwork and all proceeds go to the trust, it is essentially a tax-free solution. More artists, he says, are recognizing the importance of taking control of their legacies. Otherwise, what was once a successful career can vanish when the artist is gone, and the work can be forgotten. Yet resistance persists. Artists, notoriously averse to paperwork, often put it off—some out of procrastination, others out of a deeper reluctance to confront their mortality. “Realistically,” Ostrow concludes, “the artist needs to have a career to begin with. You can’t bank on being rediscovered if you’ve never been discovered.”

Other estates and foundations which were fortunate in their advocates include the Jay DeFeo (1929-1989) Foundation, astutely steered from its inception by Leah Levy, a close friend of DeFeo’s who saved from obscurity an art practice that consisted of far more than the incomparable, legendary Rose. Margaret Mathews-Berenson did the same for the bold, laser-edged abstractions of her friend Deborah Remington (1930-2010), with the same unshakeable belief. Choreographer and dancer Muna Tseng has been the force behind Tseng Kwong-Chi’s (1950-1990) estate ever since her brother’s death. He is best known for his East Meets West (Expeditionary Self-Portraits) photographic series, as well as images documenting the New York downtown scene in its 1980s heyday, particularly the barrage of photographs of his close friend Keith Haring joyfully painting his way through New York City. Before Tseng died of complications from AIDS at the age of 39, he asked his sister to take care of his work, regretting that he had so little time to make all that he wanted to make. She says, “He knew I would be diligent.” Now included in major exhibitions and museum and private collections, he has been discovered by a younger generation of artists, and curators, writers, galleries, and collectors are coming to the estate. “I don’t need to knock on doors anymore,” Muna says with a smile.

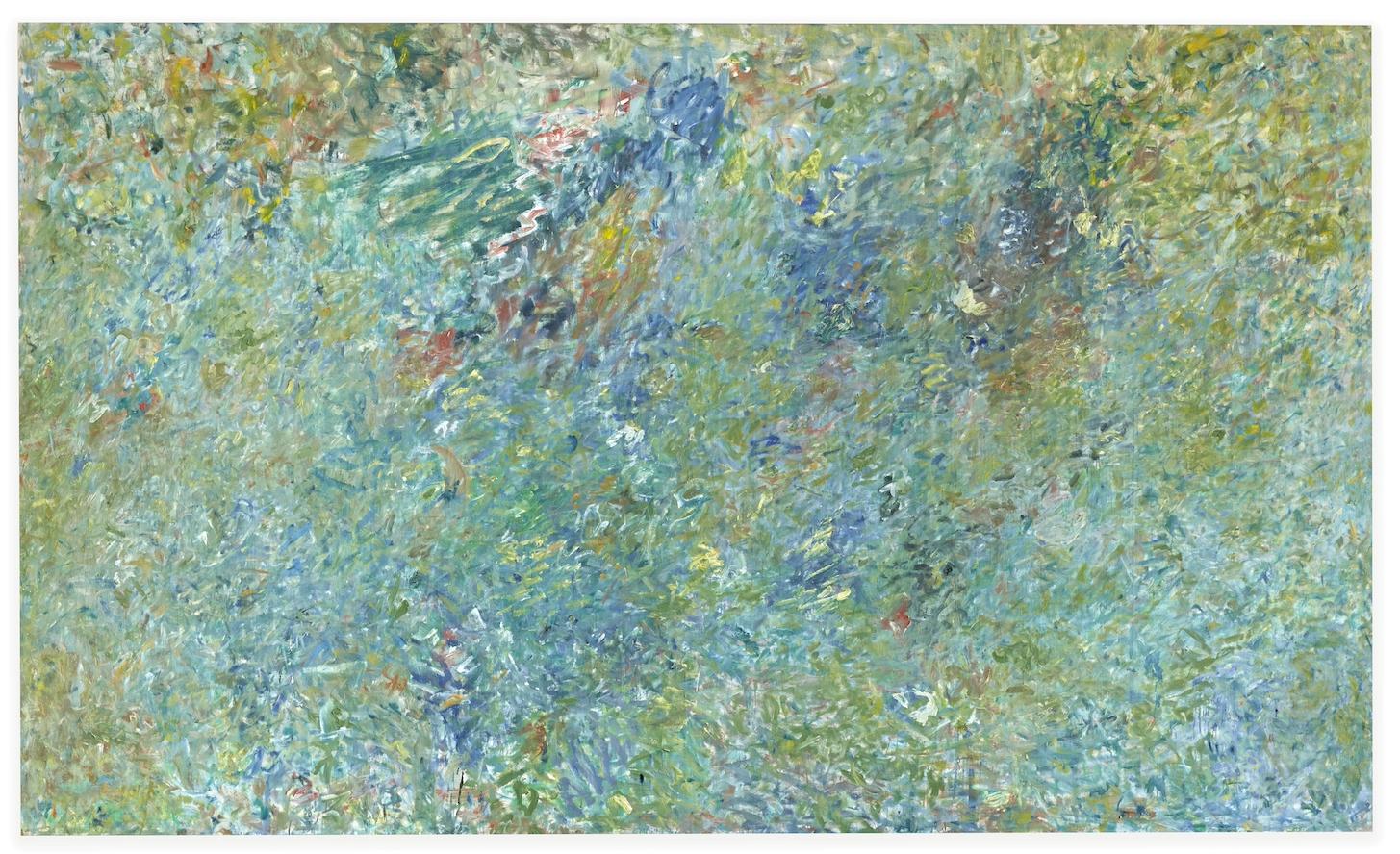

Another rescue mission focused on Mildred Thompson (1936-2003). Curator Melissa Messina, a former student of this pioneering but under-known artist, felt a profound responsibility to preserve her legacy after Thompson died. She founded the Mildred Thompson Estate and the Mildred Thompson Legacy, a nonprofit headquartered in Thompson’s house with plans to support artists that include a residency program. Placing the work of a Black, queer, female abstract painter into the mainstream was immensely challenging, but Messina saw opportunity for Thompson in the growing calls for diversity. Another crucial turning point came when Mary Sabbatino of Galerie Lelong agreed to represent Thompson’s work, despite her lack of a sales record, after seeing her painting at the New Orleans Museum of Art. “I couldn’t get it out of my mind,” she told Messina. For Sabbatino, representing such an “estate offers the incredible opportunity to rediscover and recontextualize an artist’s work for a new generation.”

Like the others, Messina understands that there is no one formula, but without a gallery to provide visibility and context and procure sales, “nothing will happen.” Nonetheless, she also believes it is essential to have someone on board who was personally involved with the artist and has an unwavering belief in the artist’s work.

To underscore that point, how many people ask how Vincent van Gogh became Vincent van Gogh? When he died, he was a complete unknown, and no one was interested in his art, but thanks in no small part to the crusade of Jo van Gogh-Bongers, the determined young widow of his brother Theo and his legacy’s unlikely guardian angel, he became the most famous artist in the world. As the artist Geoffrey Dorfman put it, saluting his wife, the artist Tracey Jones, for sorting out the chaos of the estate of the abstract painters Milton Resnick (1914-2004) and his wife, Pat Passlof (1928-2011), “Everyone needs a champion.”