One of the original HEAR Act’s more prominent success stories was the recovery of two drawings by Egon Schiele to the family of an Austrian Jewish cabaret performer who died in 1941 at the Dachau concentration camp. The New York State Supreme Court’s 2018 ruling restored Woman in a Black Pinafore and Woman Hiding Her Face to his heirs. Both drawings were in the possession of a London art dealer who purchased them several years earlier from a gallery in Switzerland.

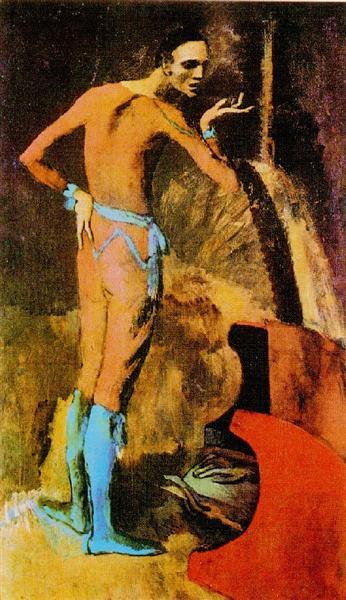

Less successful was a bid to return Pablo Picasso’s The Actor to the great-grandniece of a German Jewish businessman who sold it under duress after fleeing the Nazis to Italy. While a lower court ruled that heirs failed to prove duress, the appeals court upheld the dismissal on different grounds, citing unreasonable delay in filing the lawsuit since the painting had been in the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s possession since 1952. Amendments to the HEAR Act make that argument invalid if used in courts today.