1. The Louvre was Once a Fortress and Royal Residence

Though it’s now known for its renowned art collection, the Louvre began its life as a fortress in the 12th century designed to protect what was then the western edge of Paris. Built by Philip II, the medieval fortress featured a 98-foot tall keep and a moat. It was used to defend the city until Paris grew and other defensive structures were built on the new outskirts of the city in the 14th century.

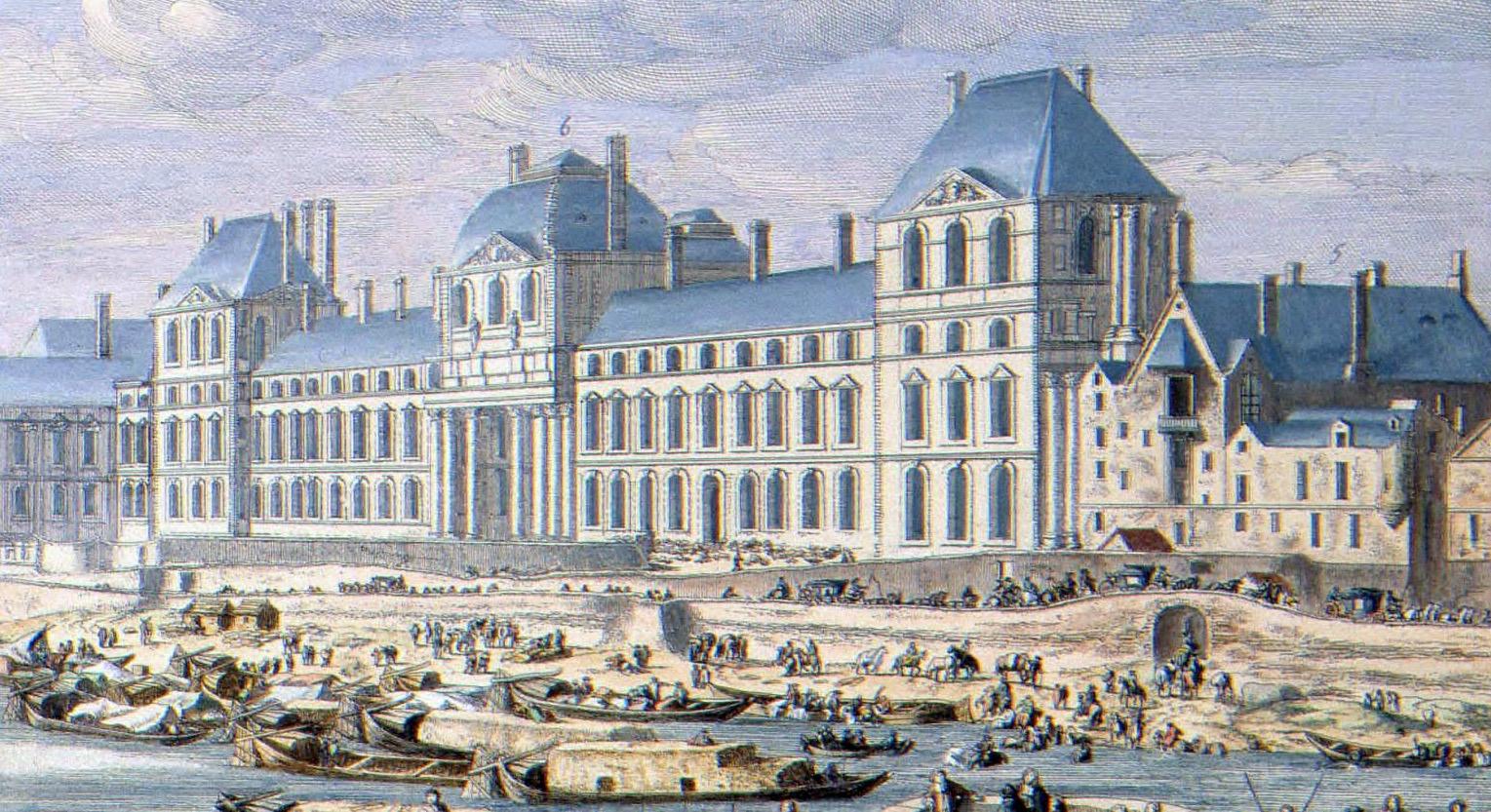

In the 16th century, however, Francis I demolished the original fortress and rebuilt the Louvre as a Renaissance-style royal residence. It continued to house the royal family until 1682 when Louis XIV built the Palace of Versailles.

Part of the medieval structure can still be seen today in the Louvre’s Salle Basse, built in the 13th century.