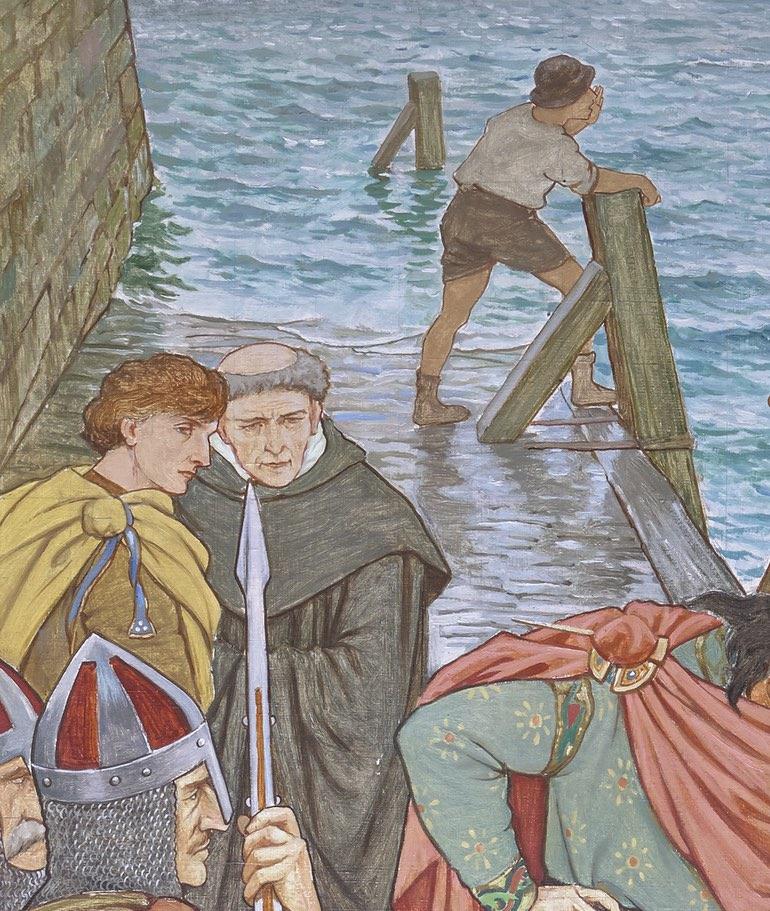

The artist created The Landing of St. Margaret at Queensferry, A.D. 1068, in 1899, in a highly detailed style with numerous figures and copious colors and details. It is no wonder that Hole is majorly responsible for the animated style being used in illustrated children’s Bibles even today.

Born circa 1045 to a family that valued her education, Margaret married King Malcolm Canmore of Scotland who, records indicate, was attracted to both her intellect and her intelligence. She was twenty-four when they married, this late age for the time seems to indicate her father was waiting for a good fit for his daughter.