Envy, lust, love, anger, happiness, sadness, fear, jealousy. In one word: Feelings. Some say they are what make us human, others spend their lives learning not to be dominated by them. Whether you side with the former or the latter, it is undeniable that feelings are one of the most fascinating aspects of life. How do we, as humans, express them? Thanks to the forty-two muscles in our faces, we can convey an incredible number of emotions—more than 10,000.

And yet, researchers estimate that there are only six universally recognized facial expressions: fear, anger, disgust, happiness, and sadness. Recent studies—such as those conducted by the American sociologist Arlie R. Hochschild—illustrate that emotions are social products. This means that each culture will have its own variations and blueprints to guide how we manage and express feelings within our own communities.

From the Mesopotamian and Egyptian statues of gods with impassive and dignified expressions to Caravaggio’s drama, artists have long been exploring human feelings through a variety of media and different perspectives.

Love and anger, opposite as well as complementary forces, provide us with some of the most captivating examples of the representation of emotions through art.

LOVE

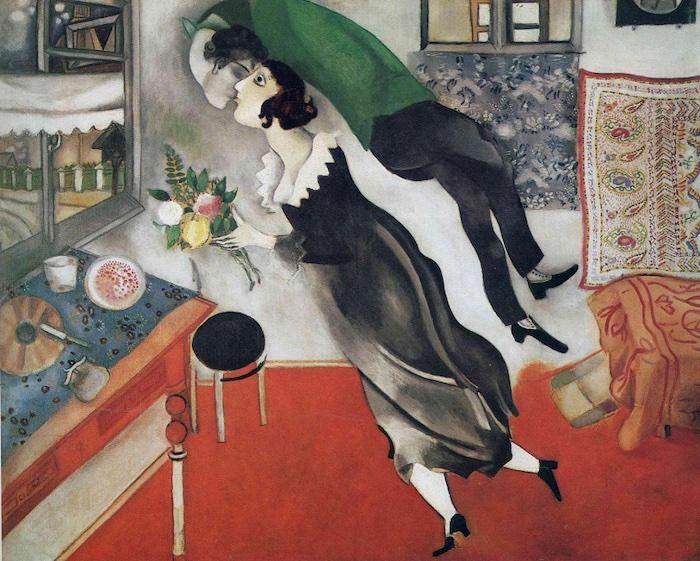

Love can take many forms: it can be the affection between parents and children, the passion of two lovers, or, for those who believe, it can take the form of faith. Among the most famous paintings on love is Birthday by the early Modernist Marc Chagall (1887-1985).