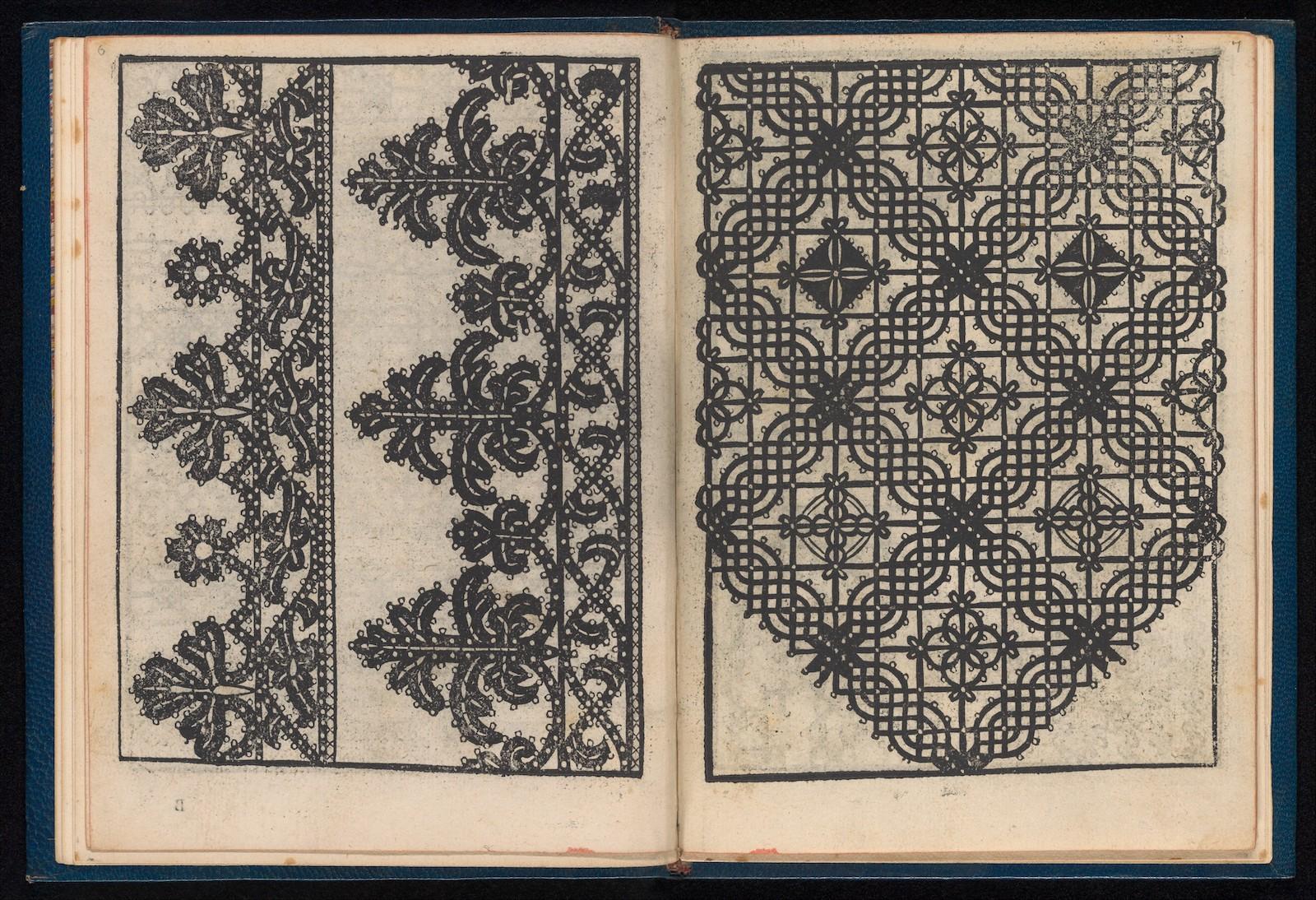

Evolving from other domestic fiber art such as embroidery and cutwork, the two distinct lace techniques—needle lace and bobbin lace—emerged simultaneously.

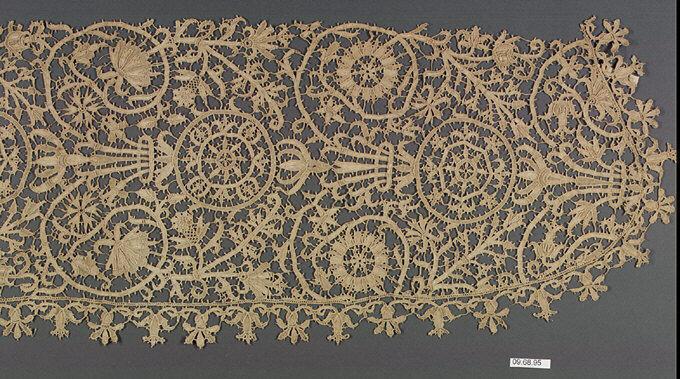

In the simplest of terms, needle lace is constructed by using a single needle, thread, and hundreds, if not thousands, of small stitches to develop the desired design. Punto in aria, or stitch in air, was the earliest form of needle lace with the woven web of thread having the capacity to be snipped from the baseted fabric or parchment.

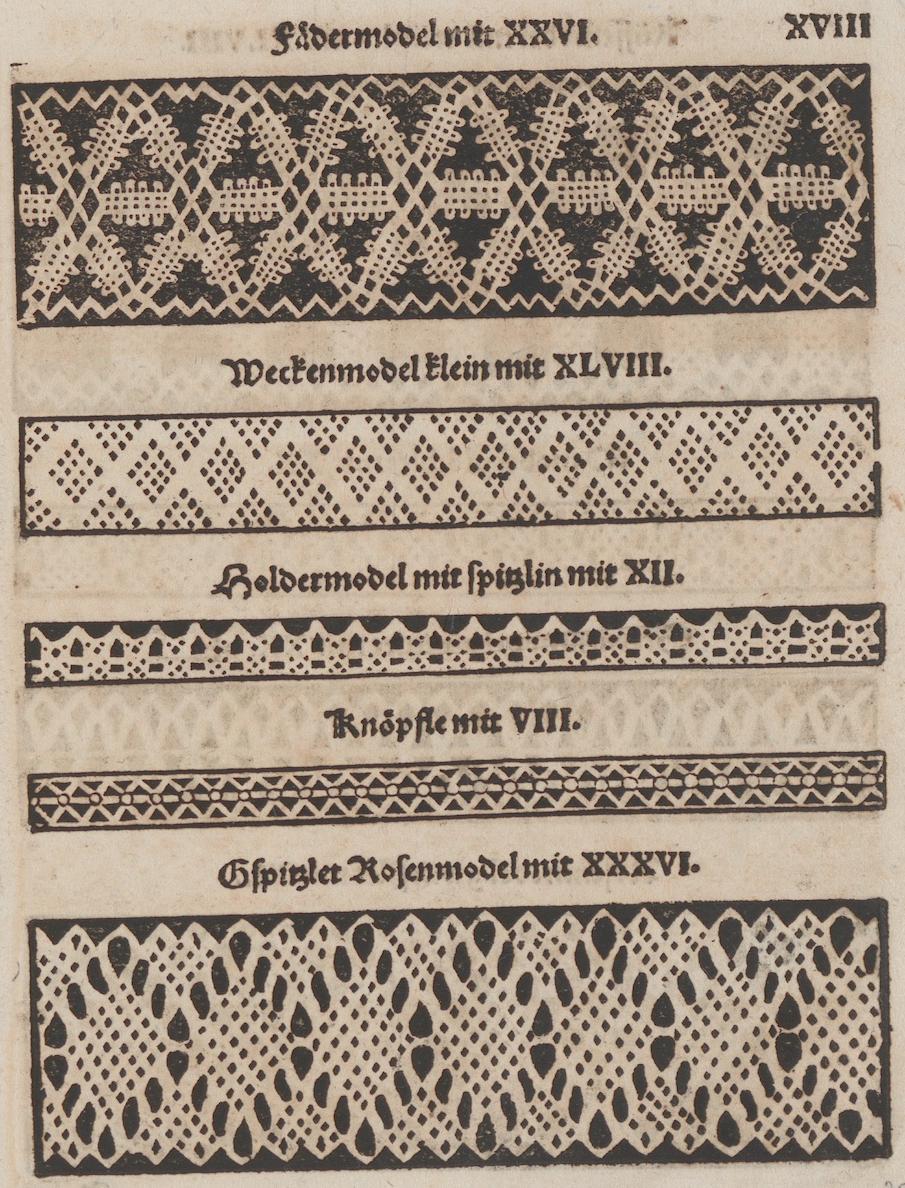

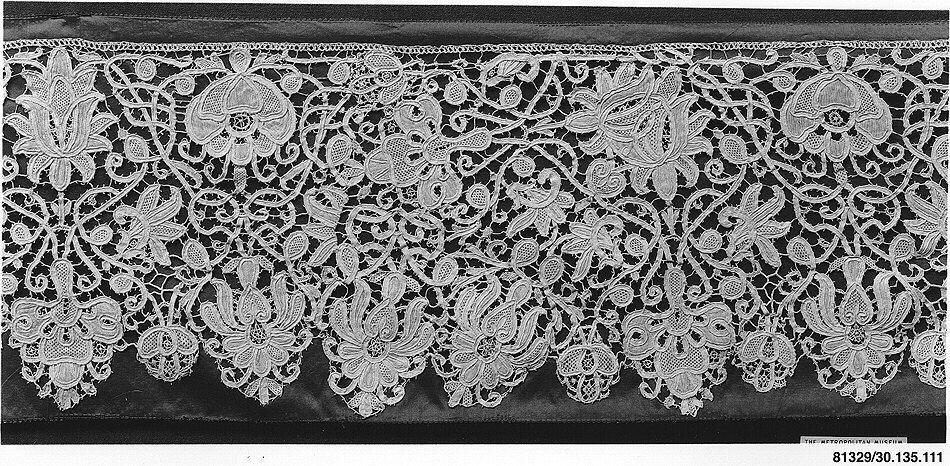

Bobbin lace utilizes a pillow, thread, countless pins, and dozens of bobbins; plaiting and twisting the many threads to intertwine its intricate pattern. Most techniques and styles for the lace are named after the cities of their inception, such as Chantilly, Mechlin, Brussels, and Honiton. However, with the growing consumer demand for innovative motifs and quality, the production of city-specific laces could be manufactured in varying regions thanks in part to the accessibility of lace pattern books.