As a part of this imperial process, goods and people began moving around the Mediterranean basin and beyond at unprecedented rates and volume– including art and artists. Roman elites developed a rabid appetite for foreign art that was entering Italy from conquered territories, especially from Greece; their villas and gardens quickly filled with sculptures, paintings, and other decorative objects. Art soon became a commodity for socio-economic exhibitionism in a way that it had not been so before.

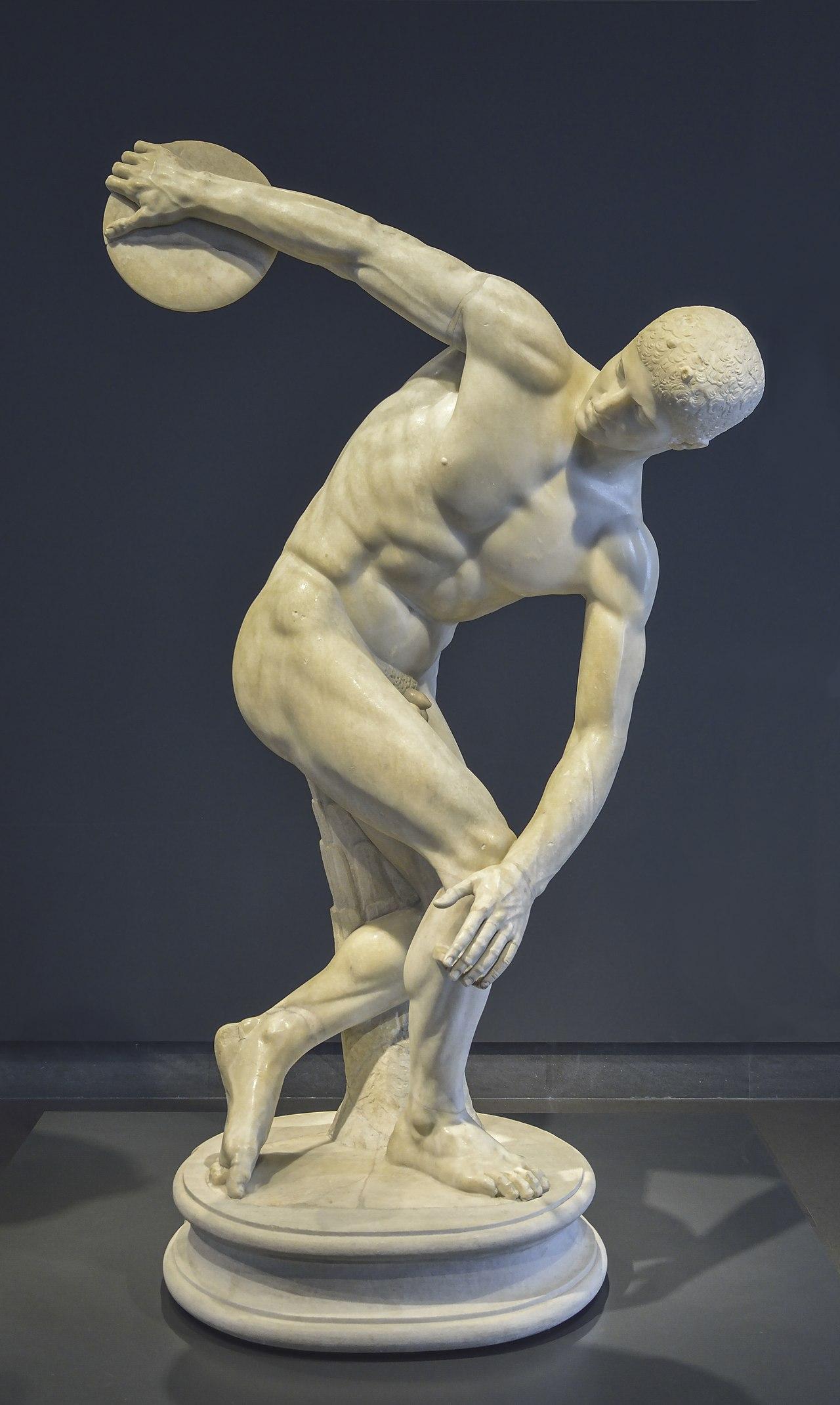

Once Roman desires for Greek art outpaced the number of original works available, artists themselves began moving to Rome to create copies of the great works such as the Aphrodite of Knidos, the Dying Gaul, and the Discobolus. It is because of this copy market that we even know what many of the Greek masterpieces looked like as most originals have long since been lost.