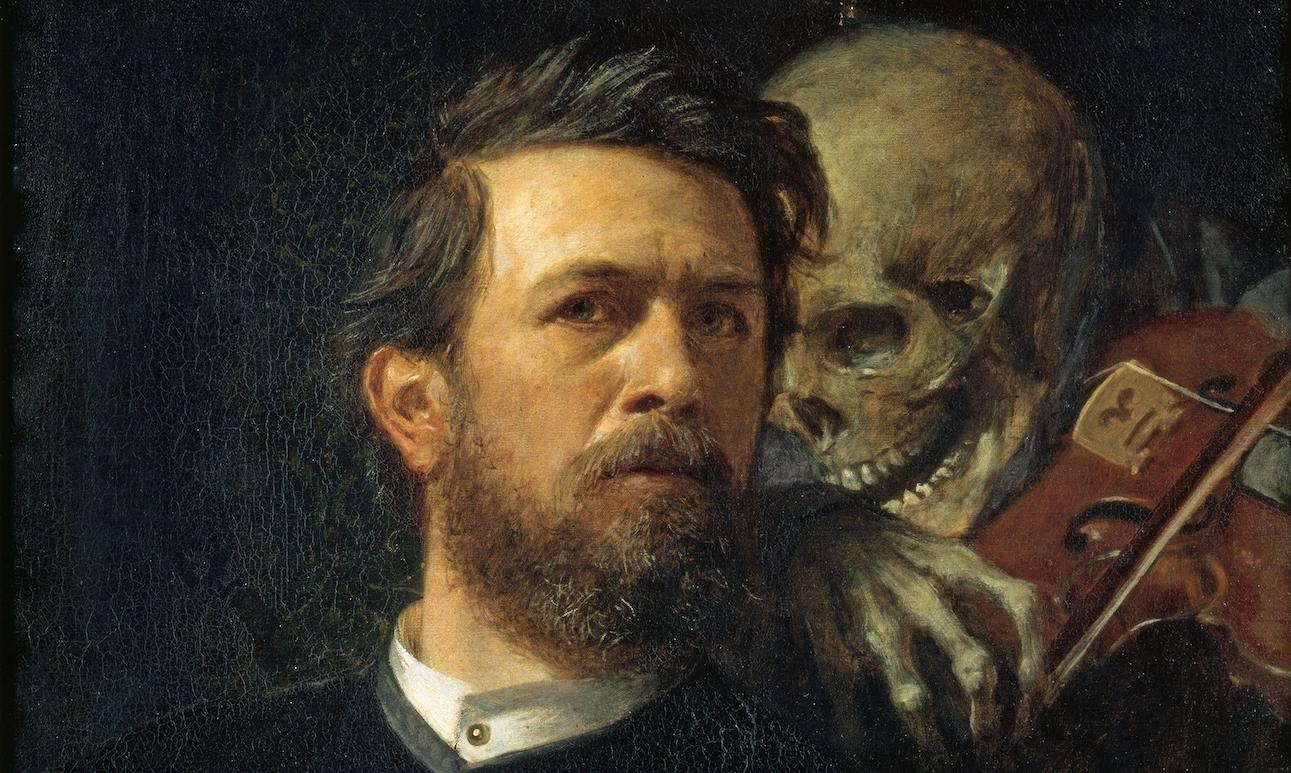

An Egyptian funerary scroll from 1050 BCE, depicts the Chantress of Amun undergoing Nauny’s ritual, post-mortem weighing of the heart. Isis, Anubis, and Osiris surround the Chantress; she holds her eyes and heart, waiting for the scales to level and reveal the final judgment of her gods. While this work does not depict the exact moment of the Chantress’ demise nor a singular personification of Death, these deities are each associated with death in some way and thus undertake duties of assessing morality and guiding her into the afterlife.

In the context of ancient Greek myth, one might initially think of Hades, Charon, or the Fates. But it is the minor god Thanatos who is the physical embodiment of Death. The son of Erebus and Nyx, and the twin of Hypnos, Thanatos' sweeping wings and gentle touch brought even the strongest of warriors to their graves. Although this and other ancient depictions of Death are a far cry from modern interpretations, in giving physical form to the abstract concept of death, these cultures laid a vital foundation for later representations.