Similarly, the Belgian artist Van de Woestyne explored work across various media and found solace in artistic communities modeled in part on Medieval guilds. His work seeks out iconography with archetypal resonance, such as the strong peasant farmer seen in The Bad Sower (1908). The long, drawn faces of his figures bear a resemblance to those of Van Eyck and other early Northern artists, while his subject matter is drawn from biblical parables popular in the Gothic period. Here, the enigmatic portrait is less about the individual and more about the very soil in which he toils and from which he draws his strength and therefore becomes a means of visually affirming mankind’s connections to nature.

In a 1905 publication, the French critic Joris-Karl Huysmans recounted his travels in Germany at the end of the century, championing a trinity of German Gothics—Dürer, Cranach the Elder, and Hans Holbein the Elder—along with the visceral emotionalism of Grünewald’s masterworks such as the Isenheim Altarpiece (1512-16). The large scale, multi-opening composition was commissioned for a hospital chapel at an Antonite order monastery in Colmar. The complex primarily treated those afflicted with skin ailments, including Saint Anthony’s fire (ergotism), contracted from contaminated rye. The twisted, gnarled, and contorted body of the crucified Christ was intended not only to relay explicit Germano-Gothic stylistic conventions but also to empathize with the afflictions of the site’s patients. For Huysmans, the work was an exemplar of art’s power, and a model for what the catalogue essayists call “the expressive turn” at the fin de siècle.

Writing in 1916, in the midst of World War I, the critic Walter Benjamin found in Grünewald’s composition a startling representation of the grim realities of existence and a mirror for the nightmarish conditions of human conflict. Subsequent artists drew from the violent intensity found in the Gothic to help express not only their experiences of the war but a world shattered in its wake. In Käthe Koll- witz’s Hunger (1923) a jagged, skeletal mother is wracked with grief. Clutching her head, her mouth open in an almost primal cry, she grieves the dead child in her lap. The composition’s emotional intensity mirrors that of the Gothic past, here also evoking historical representations of the Pietà.

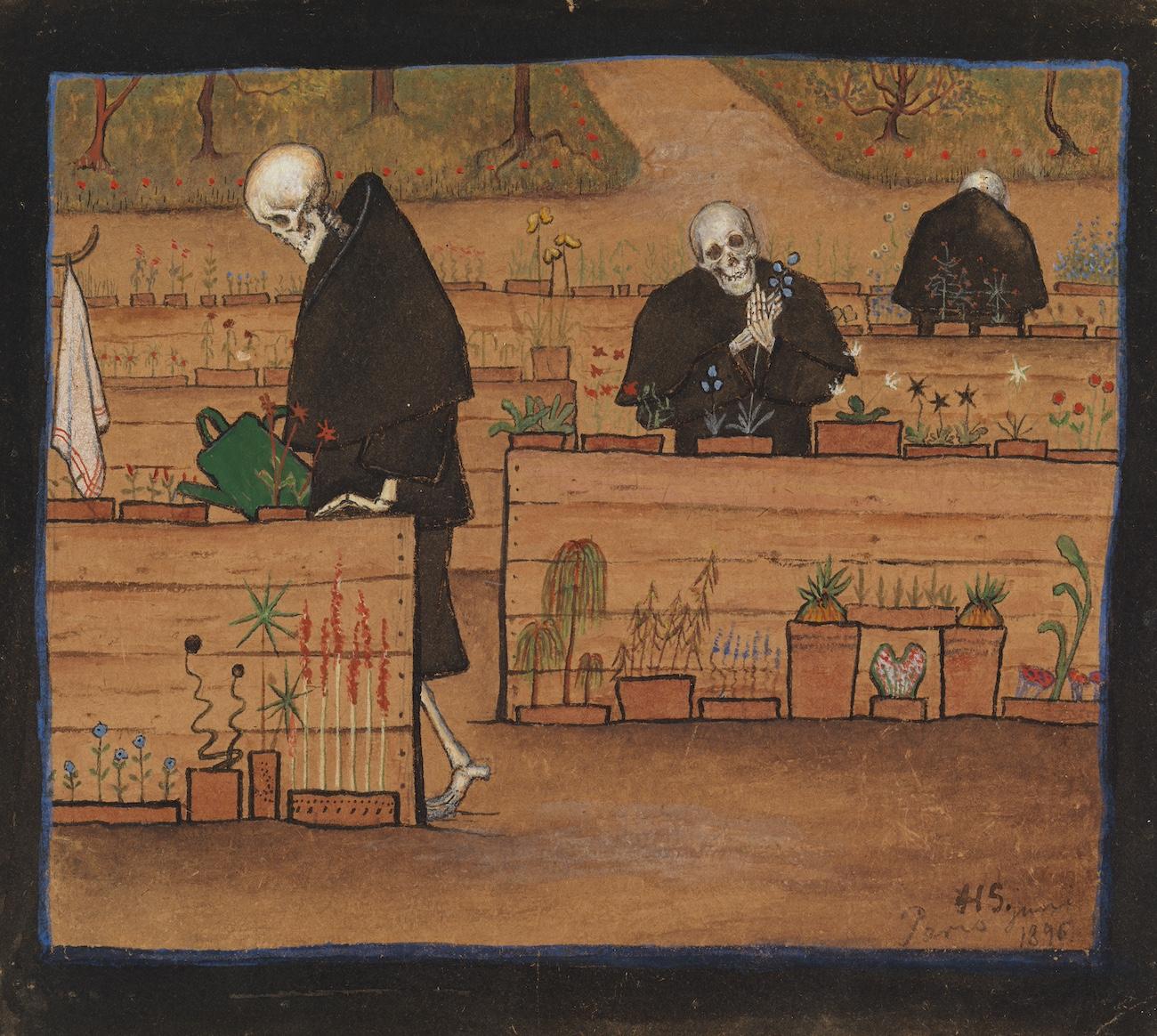

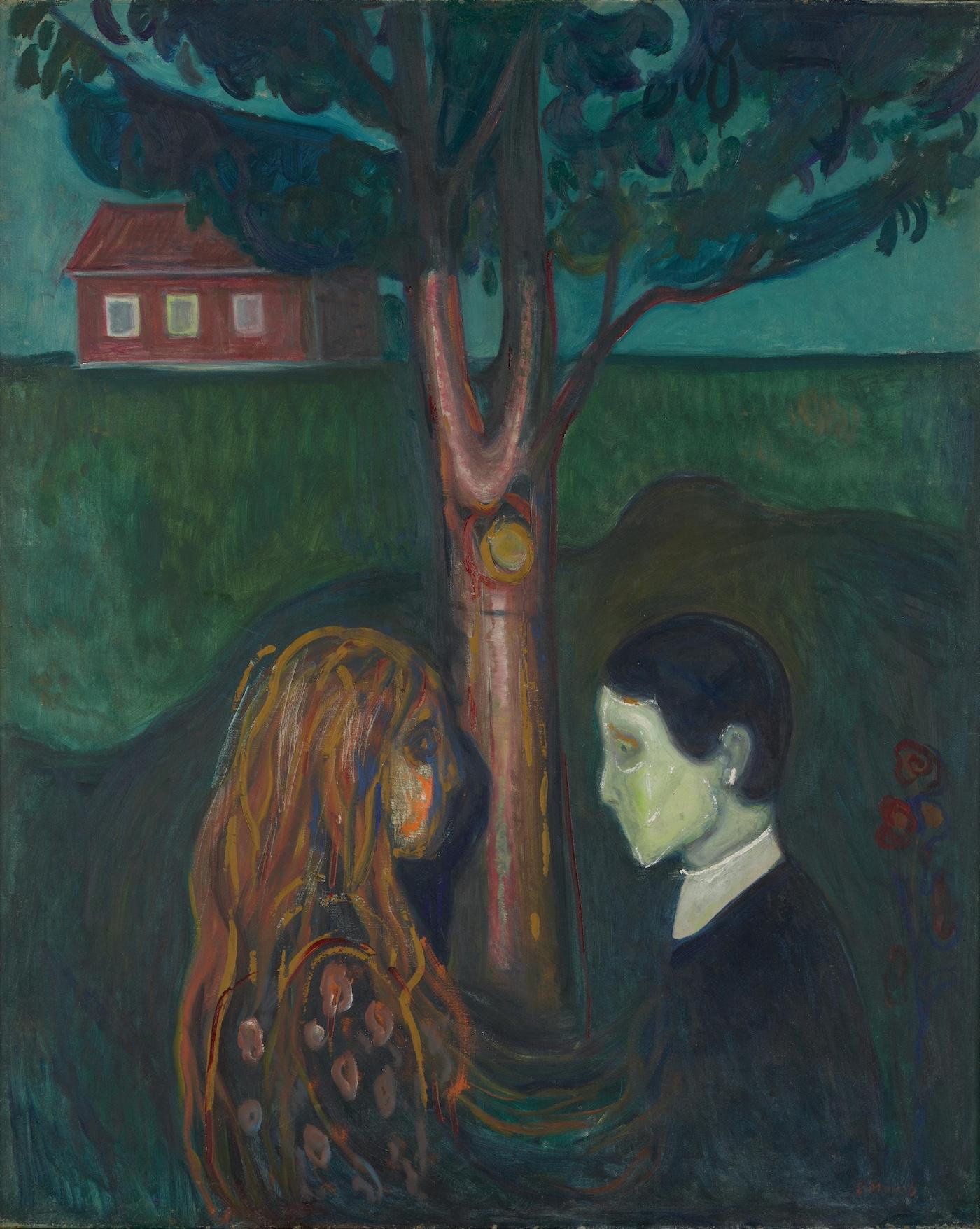

Other work on display in the exhibition engages with the Gothic imaginary via repeated subject matter. The exhibition highlights the Gothic Modern’s fascination with and translation of the Danse Macabre or Totentanz (Dance of Death). In this Medieval trope, a “dance,” or confrontation between the living and the dead, stands as a symbolic reminder of the frailty of existence and mortality, a message that in a religious context was intended to emphasize the importance of Christian salvation. For turn-of-the-20th-century viewers and artists alike, the motif also provided a means of responding to the harsh realities of modernity, an era of overwhelming uncertainty. What more is there to understand about life than the certainty of death?

By studying the Dance of Death’s historical origins, the curators present a re-reading of well-known works such as Van Gogh’s Head of a Skeleton with a Burning Cigarette (1886). Often dismissed as a crude joke from his school days, the work now evinces Van Gogh’s engagement with and modernization of age-old symbolism. More impressive are Finnish painter Simberg’s multiple renderings of the theme. Dance on the Quay (1899) shows two dark-suited skeletons twirling and dancing with peasant children lakeside on a dock. Based on the responses of their dance partners—one a young girl flush with excitement, the other tentative and unsure—we see a gentle, almost humorous depiction of the tragedies of existence. Simberg seems to suggest that in an era of u certainty we can only grasp at fleeting joy and laugh in the face of danger, willfully holding fast to the present and ignoring the possibility of future tragedy.

The “Gothic Modern” project began in 2018, prior to the pandemic, the war in Ukraine, and other contemporary tensions, which, the curators point out, bear a stunning resemblance to the world in which these earlier modern artists found themselves. Rife with trauma, tension and fear, ours is a world that shares an affinity with both the Gothic and the Gothic Modern, which makes these movements more relevant than ever. The exhibition offers viewers the opportunity to also time travel, to look back upon the past as a means of con- fronting the challenges of today.