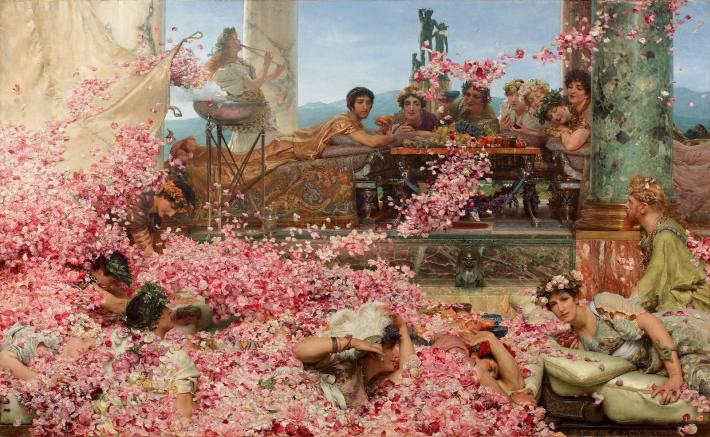

Alma-Tadema, The Roses of Heliogabalus, 1888. Oil on canvas.

If one symbol represents love, power, royalty, beauty, sensuality, and mysticism–it is the rose. Also known as "the queen of flowers," the flower as we know it dates back to at least the oligocene epoch (about thirty-three to twenty-three million years ago). While much like camellia and azalea, it most certainly originated in the area that now corresponds to Southwest China, it has appeared across cultures since 3000 BCE. This slide show will focus on the prominence of roses in Western art from the first millennium BCE to the twenty-first century CE.

Unknown, Fresco Fragment with Four Cupids Hanging Garlands, third quarter of 1st century. Fresco. J. Paul Getty Museum.

In Ancient-Greek Civilization roses were linked with deities such as Aphrodite, Eros, and Dionysus. Rose wreaths were worn by virgins and banquet revelers alike. Romans were obsessed with roses, using them in their cuisines, in their cosmetic products (most notably, rose oil), and as an element of ornament in their frescos. For example, a fresco of the house of the Golden Bracelet in Pompeii shows a rose in various stages of bloom. A fresco in Villa Farnesina features a woman pouring rose oil into a flask.

Alma-Tadema, The Roses of Heliogabalus, 1888. Oil on canvas.

During the Roman Empire, the rose came to be so adored that each May a festival known as Rosalia or Rosatio was held. At this time, roses were not gendered as an ornament. "Long before flowers were gendered feminine, rose wreaths or chaplets (tight circlets worn on the head) and garlands (longer, strung) played a vital role in economic, domestic, religious, and ceremonial life," wrote Amy de la Haye in Ravishing, a catalogue exploring the influence of roses in fashion and the arts, a companion of the upcoming FIT Museum show of the same name. "They were awarded to men for great acts and virtues [...] and it was men who wore perfume made from roses."

Michelino da Besozzo, Madonna of the Rose Garden, 1435. Castelvecchio Museum.

The rose maintained, and actually acquired, even stronger symbolism in the Middle Ages, as color became a critical component. Red roses were symbolic of Christ’s blood—and, by extension, of martyrs— and white roses of the Immaculate Conception. In the fifth century, the poet Coelius Sedulius identified Mary as "rose among thorns," while St. Bernard (eleventh century CE) described her as "the violet of humility, the lily of chastity, the rose of charity." Roses were a typical ornament in garden enclosures or hortus conclusus. These gardens as a whole also symbolized Mary's purity. Michelino da Besozzo's Madonna in the Rose Garden, a painting of the International Gothic tradition from the fifteenth century, is an example of this. Throughout this period, Mary is associated with red and white roses in equal measure. Madonna of the Rose Bower, a panel by the fifteenth-century painter Stefan Lochtner, shows a regal version of the Virgin Mary under an archway of roses, both white and red.

Jan Davidsz de Heem, Still Life with a Skull, a Book, and Roses, 1630.

Dutch and Flemish seventeenth-century masters heavily featured roses in their still-life paintings, either in juxtaposition to flowers with different blooming patterns or placed next to a skull. Jan Brueghel the Elder painted lush bouquets with botanical precision, with the former motif to remind viewers of their mortality. Jan Davidsz de Heem, encapsulated the latter in his Still Life with a Skull, a Book, and Roses, which contrasts death with the pleasures of life." This idea became known as vanitas painting (reminding the viewer of their mortality) or memento mori, combining the real, the ideal, and the symbolic in one vase," writes rose curator Peter Kukielski in Rosa, now out from Yale University Press.

Rachel Ruysch, Roses, Convolvulus, Poppies, and Other Flowers in an Urn on a Stone Ledge, 1688.

In the Dutch Golden Age of Art, Rachel Ruysch became the most prominent still-life painter. The daughter of a botanist, she painted iconic still-lifes of flowers, marked by asymmetrical views and an emphasis on contrasting textures. Roses, Convolvulus, Poppies, and Other Flowers in an Urn on a Stone Ledge, for example, juxtaposes the fleshy texture of rose petals to the jagged edges of milk thistles and depicts the thorns of the roses with precision.

François Boucher, Madame de Pompadour, 1756. Alte Pinakothek.

In the Rococo era, roses became a fashion statement in the French court. Madame de Pompadour, Louis XV's official mistress, established herself as the leader of fashion at the court of Versailles, and several portraits depict her in opulent gowns where rose embellishments are the main adornment. In a François Boucher portrait, she sports a green silk taffeta gown.

Élisabeth Louise Vigée Le Brun, Marie Antoinette with a Rose, 1783.

Roses were also heavily featured in Marie Antoinette's portraiture. In a portrait by Elisabeth Vigée LeBrun, she wears the opposite of contemporary courtly attire—a loose-fitting chemise fastened at the waist with a sash. This was the height of her pastoral phase. The portrait was deemed scandalous for how disheveled the queen appeared, so Vigée LeBrun later painted her in the same pose but in a court-appropriate gown.

Vincent van Gogh, A Vase of Roses, 1890.

Roses remained a popular subject for still-life painters through the nineteenth century: among these are Vincent van Gogh's Vase of Roses (1890) and the Roses series of late-nineteenth-century French painter Henri Fantin-Latour. The late nineteenth century also brought about revivalism and idealization of the Medieval and Ancient past. This often manifested in overly opulent paintings of revelries that featured figures from the Roman Empire or fair maidens of the Middle Ages. In 1890, Thomas Ralph Spence depicted a sensuous version of Sleeping Beauty where roses somehow became an extension of her long hair.

John William Waterhouse, The Soul of the Rose, 1908.

Similarly, The Soul of the Rose, by John William Waterhouse in 1908 took inspiration from the literature of Alfred Lord Tennyson. The painting shows a woman taking in the intoxicating scent of roses in bloom. Perhaps the most opulent depiction of roses is The Roses of Heliogabalus (1888) by Sir Lawrence Alma-Tadema, which shows a banquet flooded with rose petals. The inspiration is a bizarre incident, in which the emperor Heliogabalus released a torrent of flower petals on his guests from the retractable roof of his banquet hall. Given that many were intoxicated, they were unable to crawl out of the deluge, and some ended up being smothered.

The dancer Vaslav Nijinsky in the ballet Le spectre de la Rose as performed at the Royal Opera House in 1911.

The rose's popularity continued to endure through the twentieth century. In 1911, the ballet Le Spectre de la Rose, which tells the story of a girl returning home after her first ball when her corsage comes to life as a young man. Vaslav Nijinsky originated the role, and the iconic costume, a unitard covered in silk rose petals, was designed by Ballets Russes designer Leon Bakst and needed to be stitched directly onto Nijinsky every night. In the fine art world, Georgia O'Keeffe often favored roses. "In her large-scale paintings, she wanted both to celebrate the beauty of flowers and play on their many cultural associations, while also—by making the images so large and striking—shocking people into really looking at them," wrote curator Peter Kukielski in Rosa, now out with Yale University Press.

Salvador Dalí, Meditative Rose, 1958.

In the works of Salvador Dalí, the rose symbolizes youth and beauty. He frequently painted images of a woman with a bouquet of roses in the place of her head. In a 1958 painting, Meditative Rose, Dalí places a formally perfect rose high in the sky, in place of the sun. A pair stand underneath it, the rose towering over them—it seems to be a symbol of love.

Angelica Frey

Angelica Frey is a writer and translator living in Brooklyn. She writes about art, culture, and food.