Lawrence achieved fame early on through his epic Migration Series, a 60-panel set of paintings depicting the Great Migration, the mass exodus of African Americans from the southern US to the north, where they sought greater economic opportunity. It was a familiar topic for Lawrence, who was born in Atlantic City, New Jersey in 1917, as his own parents had moved north as part of that wave.

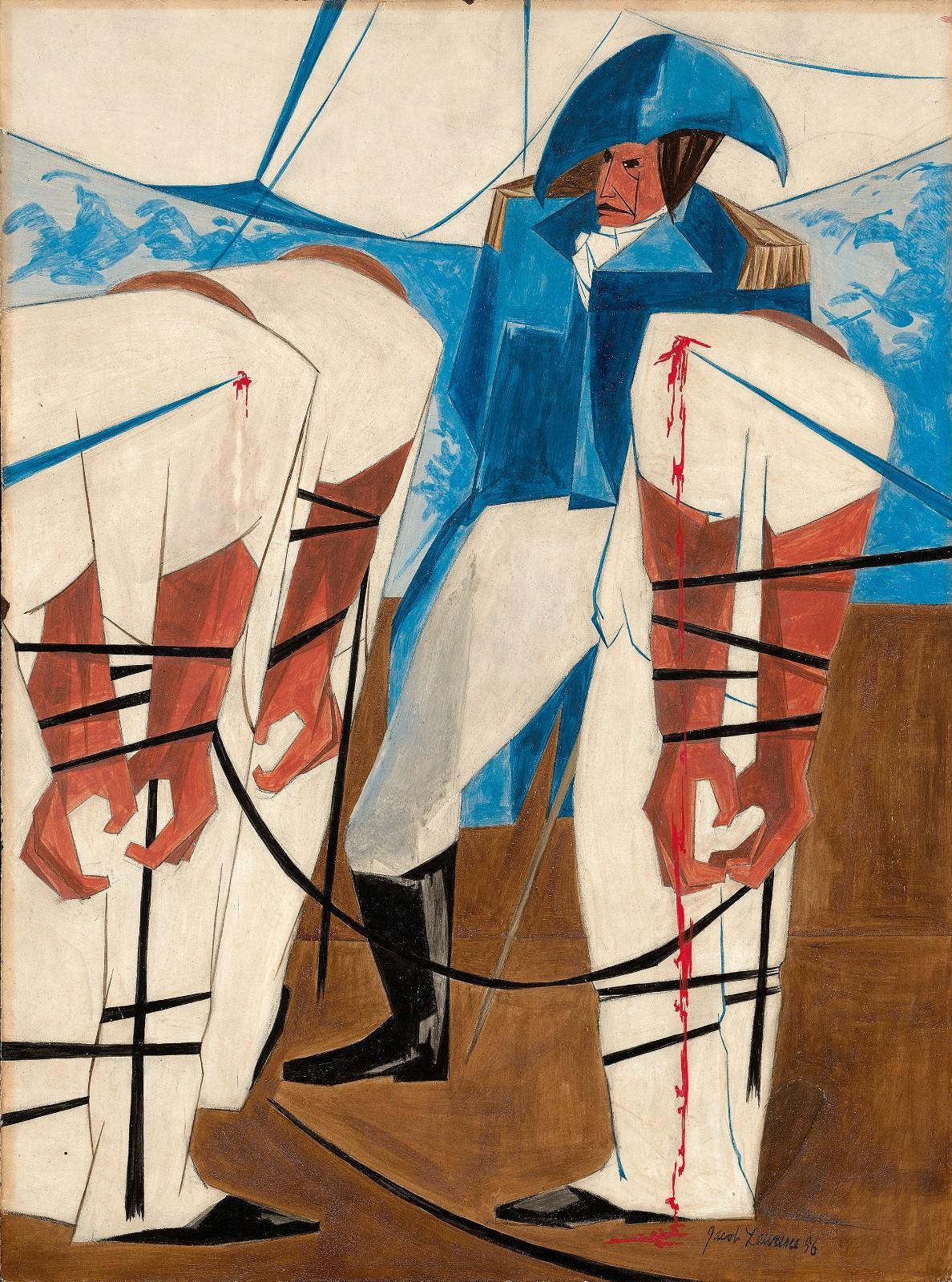

Jacob Lawrence, . . . again the rebels rushed furiously on our men.—a Hessian soldier, Panel 8, 1954, from Struggle: From the History of the American People, 1954–56. Egg tempera on hardboard. Collection of Harvey and Harvey-Ann Ross.

Long before inclusivity was a crucial lens through which we viewed everything from history to public spaces, one prominent American artist set out to correct the record all on his own. Jacob Lawrence, one of the greatest African American artists of the 20th century and a key figure in the Harlem Renaissance, used his paintbrush to highlight forgotten figures and moments of American history.

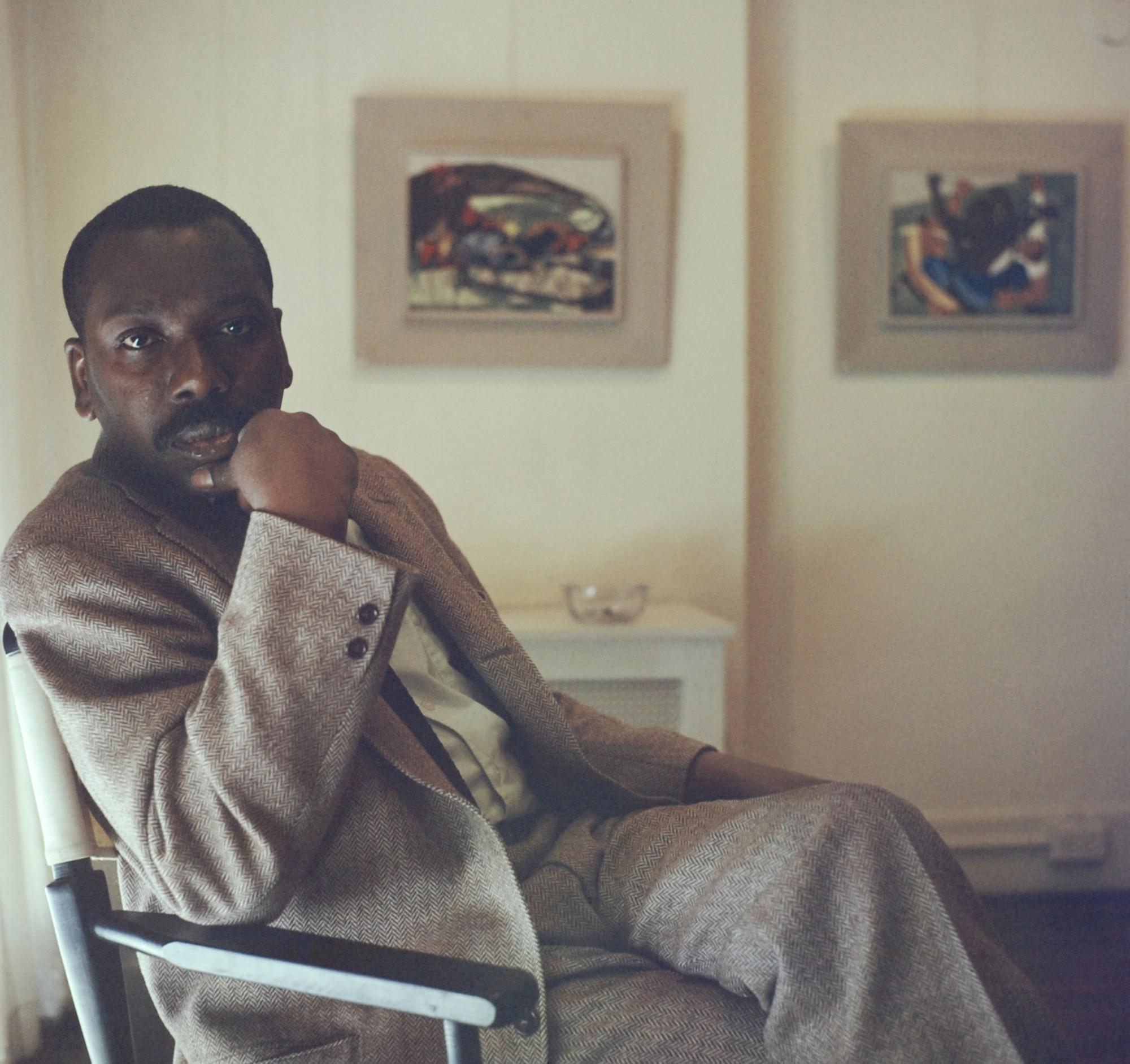

Artist Jacob Lawrence with panels 26 and 27 from Struggle: From the History of the American People, 1954–56.

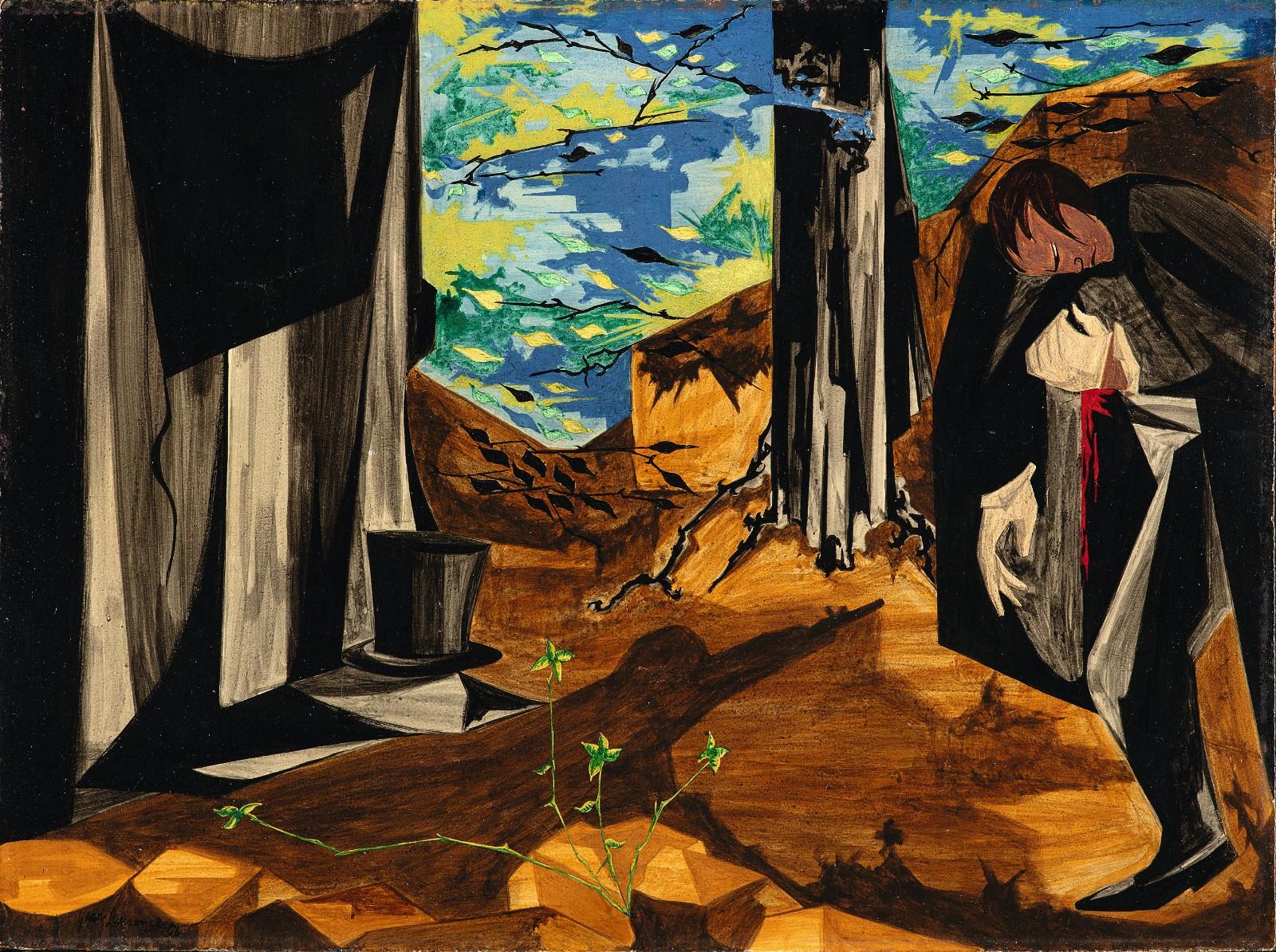

Jacob Lawrence, Thousands of American citizens have been torn from their country and from everything dear to them: they have been dragged on board ships of war of a foreign nation.—Madison, 1 June 1812, Panel 19, 1956, from Struggle: From the History of the American People, 1954–56. Egg tempera on hardboard. Collection of Harvey and Harvey-Ann Ross.

Created when Lawrence was just 23, the Migration Series, originally called The Migration of the Negro, was created from 1940-41 with funding from the Works Progress Administration. Lawrence worked on all sixty panels at once to ensure unity amongst the works and clarity of his message. The series was immediately recognized as a masterpiece and became the first work by a black artist to be acquired by the Museum of Modern Art.

After making history himself with the success of the Migration Series, Lawrence turned to the library, seeking untold stories from American history. For five years he researched at the New York Public Library, and by the time be began work on a new series in 1954, major changes in the nation had taken place and in the civil rights movement was gaining momentum. From this research Lawrence would create Struggle: From the History of the American People, a set of thirty paintings telling American history from the vantage point of women, Native Americans, and black people in Lawrence’s unique visual language.

Jacob Lawrence, We crossed the River at McKonkey’s Ferry 9 miles above Trenton. . . the night was excessively severe . . .which the men bore without the least murmur . . . —Tench Tilghman, 27 December 1776, Panel 10, 1954, from Struggle: From the History of the American People, 1954–55. Egg tempera on hardboard. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, purchase, Lila Acheson Wallace Gift, 2003.414.

Lawrence does not sugar-coat history in his paintings: many of them feature weapons and dripping blood in energetic compositions that explode with violence, and exude the desperation of conflict. The power of Lawrence’s unique style, which he referred to as "dynamic cubism" is evident in these works. His abstracted geometric forms and powerful use of color create dramatic compositions that turn moments of American history into emotional vignettes.

Jacob Lawrence, I shall hazard much and can possibly gain nothing by the issue of the interview . . . —Hamilton before his duel with Burr, 1804, Panel 17, 1956, from Struggle: From the History of the American People, 1954–56. Egg tempera on hardboard. Collection of Harvey and Harvey-Ann Ross.

By focusing on the roles of black people, Native Americans, and women, Lawrence created a fuller history of America, one that was more complex and comprehensive than the one found in most history books. Combining the political aims of social realism with the raw emotion of abstraction, Lawrence’s evocative paintings elicit empathy and understanding for the marginalized figures who were nonetheless key in these historic moments. As in the Migration Series, for Struggle, Lawrence gave each panel a lengthy title, often sourced from primary historical documents, such as letters from the founding fathers and slave narratives, that give us clues as to where they fit into history.

Jacob Lawrence, . . . is life so dear or peace so sweet as to be purchased at the price of chains and slavery?—Patrick Henry, 1775, Panel 1, 1955, from Struggle: From the History of the American People, 1954–56. Egg tempera on hardboard. Collection of Harvey and Harvey-Ann Ross.

For the first time in sixty years, these paintings are reunited under one roof for an exhibition that shows Lawrence’s brilliance, the fraught history of the US, and how far we as a nation have (or have not) come in the past six decades. Jacob Lawrence: The American Struggle in now on view at the Peabody Essex Museum, where Lawrence’s works are complemented by those of contemporary African American artists Hank Willis Thomas, Bethany Collins, and Derrick Adams, who address the ongoing struggle for democracy in their work.

Jacob Lawrence, The summer soldier and the sunshine patriot will, in this crisis, shrink from the service of his country.—Thomas Paine, 1776, Panel 7, 1954, from Struggle: From the History of the American People, 1954–56. Egg tempera on hardboard. The Renee & Chaim Gross Foundation.