However, there is a very different approach, one that strives to raise awareness by creating art rather than attacking it. Encompassing a range of artistic practices, environmental art has evolved from monumental 1960s earthworks to paintings, sculpture, and installations that drew attention to ethical, social and environmental issues in the 1990s, to current exhibitions that center on traditional indigenous practices that celebrate the interconnectedness of humanity and nature, modern society’s need to reconnect with nature, and the social and cultural aspects of climate change.

The Baltimore Museum of Art’s upcoming exhibition Black Earth Rising is an excellent current example of contemporary environmental art. Opening May 18 and running through September 21, the multimedia exhibition examines how the climate crisis and colonialism are intimately connected, through the lens of works by contemporary African diasporic, Latin American, and Native American artists, including Firelei Báez, Frank Bowling, Wangechi Mutu, and the late Jaune Quick-to-See Smith.

Inspired by the Portuguese term terra preta, or black soil—which refers to the fertile earth of the Amazon basin—Black Earth Rising traces the colonial impact on the ecosystem and culture of the New World, starting from the 16th century. Centering artists of color grappling with cultural displacement, the legacy of slavery and ecological destruction, the exhibition explores both the impact of colonialism and the healing, vibrant joy that can be found in nature.

Guest curator Ekow Eshun explains that the BMA show “involves a reframing of climate debate that places Black, Brown and Indigenous peoples at the active center rather than the edges of the discourse. In doing so, the exhibition seeks to expand the visual discourse around climate change, establishing a richer historical and cultural context from which to consider the condition of our world today.”

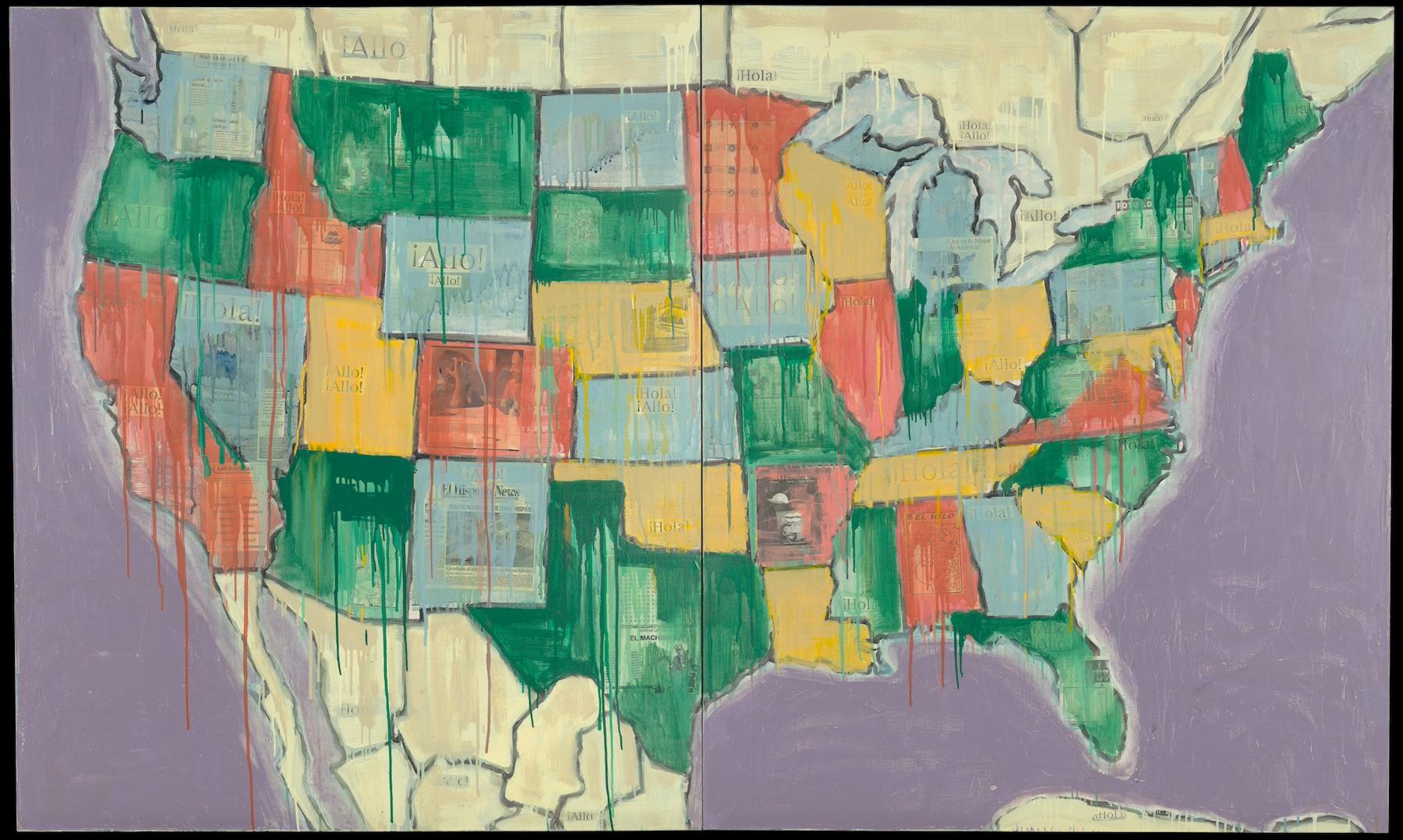

Sky Hopinka captures stunning cloudscapes in Mnemonics of Shape and Reason. Wangechi Mutu’s My Cave Call depicts a mysterious cavern. In Todd Gray’s Present History (1619), montages of historical colonialist imagery are superimposed over lush tropical leaves. In Alejandro Piñeiro Bello’s Viajando En La Franja Del Iris, vivid abstract swirls of color coalesce into a surrealistic landscape. Jaune Quick-to-See Smith’s Echo Map is a collaged depiction of the United States in alternating colors of green, red, blue and yellow bleeding anemic colors across the canvas. And in Firelei Báez’s Convex (recalibrating a blind spot), a blue wave crests against sugar-refinery statistics, with a red starburst at the center of the wave and a brown figure kneeling in the right corner.

These works all expand the “traditional” visual discourse, making artists of color the main characters and narrators. Referencing the ugly impact of slavery and the sugar trade, the artificiality of contemporary borders, the importance of reconnection and the sacredness of space, these vivid, thoughtful, even ecstatic works inspire hope while also educating viewers.

Eshun adds that the artists of Black Earth Rising “are considering weighty questions of history, power, climate crisis and social and environmental justice. But they’re not doing so didactically. They are creating artworks of powerful insight and resonant beauty. The exhibition is an invitation to explore the beauty and fragility of the natural world as seen through their eyes.”

*This article originally appeared in Art & Object's Spring 2025 issue.