Upon stepping into the Frick’s new exhibition room, audiences first encounter The Love Letter from the Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam. The smallest of the triad by a full ten inches, it surveys a maid in a brown and blue dress interrupting her mistress’ cittern rehearsal by handing her a letter. The scene is cramped, framed by a darkened hallway or closet with household items— the maid’s unglamorous domain.

Viewers are allied with the servant as she bemusedly facilitates her mistress’ courtship. The maid’s cheeky smile bolsters her nervous employer and informs audiences of the nature of the missive; witnesses are allowed into the romantic comedy and charmed by the scene.

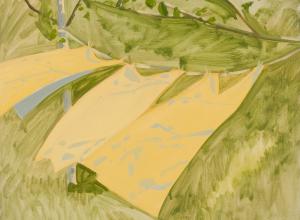

The second painting, just left, is Mistress and Maid of the Frick’s own collection— notably, Henry Clay Frick’s last acquisition before his death in 1919. The women in this scene are dressed identically to those in Love Letter, creating a progression of exchanges; where Love Letter saw a reception, Mistress and Maid witnesses the woman in the pale yellow, fur-lined gown drafting a response. She holds the pen loosely by its end, mid-thought rather than mid-action, when her brown and blue clad maid interrupts her with another letter.