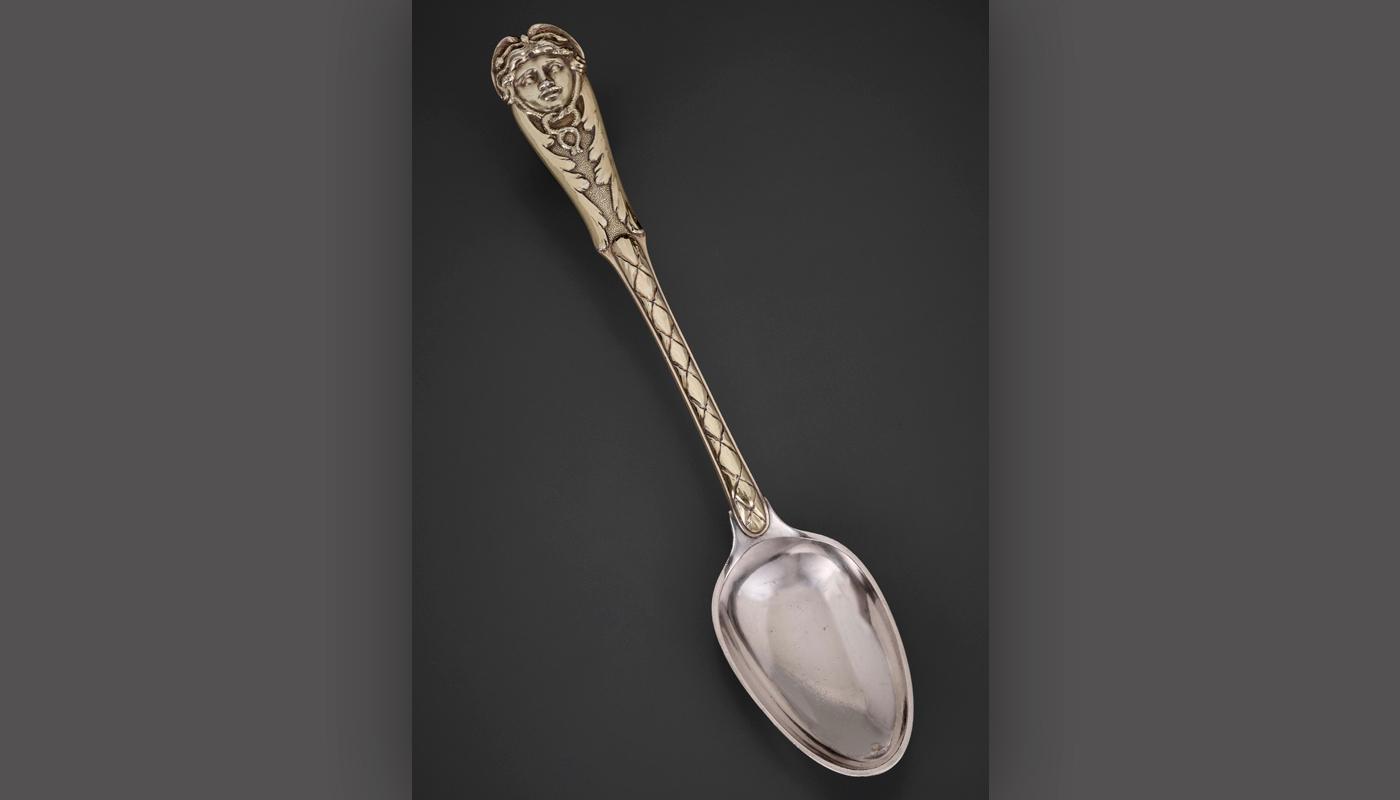

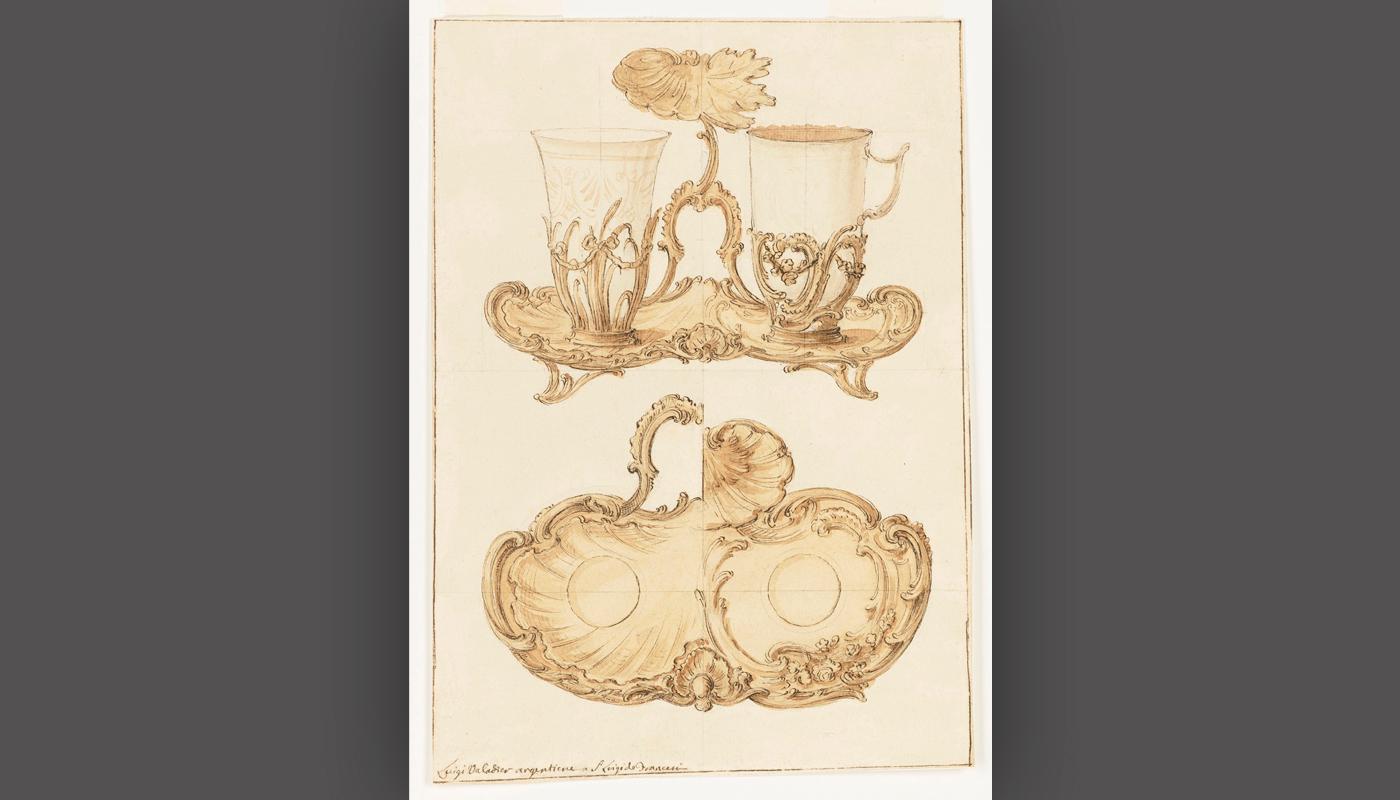

Today, Valadier’s name is no longer prominent. Much of his elaborate metalwork was melted in the decades following his death. A small 1783 spoon adorned with the face of Medusa, for instance, is one of the few extant pieces from a huge silver service he crafted for Rome’s Borghese family. Others, like his bombastic desers, were broken apart. For Luigi Valadier: Splendor in Eighteenth-Century Rome, on view at the Frick in New York in 2018, Breteuil’s deser, now divided between two institutions in Spain, was reunited. Over fifty objects and drawings joined it in visualizing what survives from Valadier’s oeuvre, with drawings and inventories hinting at what has been lost.

“We’ve been doing a series of exhibitions at the Frick on great artists in the decorative arts who are not very well known by the public,” said Xavier Salomon, the Frick’s chief curator. Luigi Valadier follows the Frick’s 2016-17 exhibition on 18th-century artist Pierre Gouthière who created gilt bronze work for the French Court. Similarly, it was the first monographic exhibition to examine Gouthière’s career. “They’re just great figures who produced works of art for the most important patrons in the world, but are now lesser known,” Salomon added.