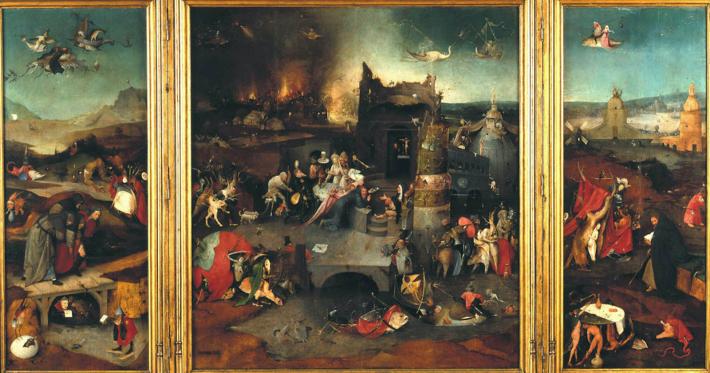

Hieronymus Bosch, detail from The Temptation of St. Anthony, c. 1501. Oil on oak panels. 52 in × 90 in. Museu Nacional de Arte Antiga.

Hieronymus Bosch (1450-1516) is one of art history’s most mysterious and fascinating artists. His work was popular in his lifetime and he received many commissions from abroad but very little is known about the Dutch artist outside of his general demographics. Less than twenty-five paintings extant today are attributed to Bosch.

His bizarre, jam-packed landscapes have therefore proved an easy target for conjectures. Bosch has been called a heretic, mentally unstable, and the Father of Surrealism—an art movement born centuries after his death.

It is now largely agreed that Bosch’s paintings were made with very specific intentions in mind to instruct and communicate. The artist used traditional symbols but also created his own, referencing the Bible and Flemish folklore to create unique visual manifestations of established metaphors and puns. All of this is to say, the moralistic bent of Bosch’s paintings—however fantastical their imagery—do fall seamlessly in line with the didactic literature of the late medieval period.