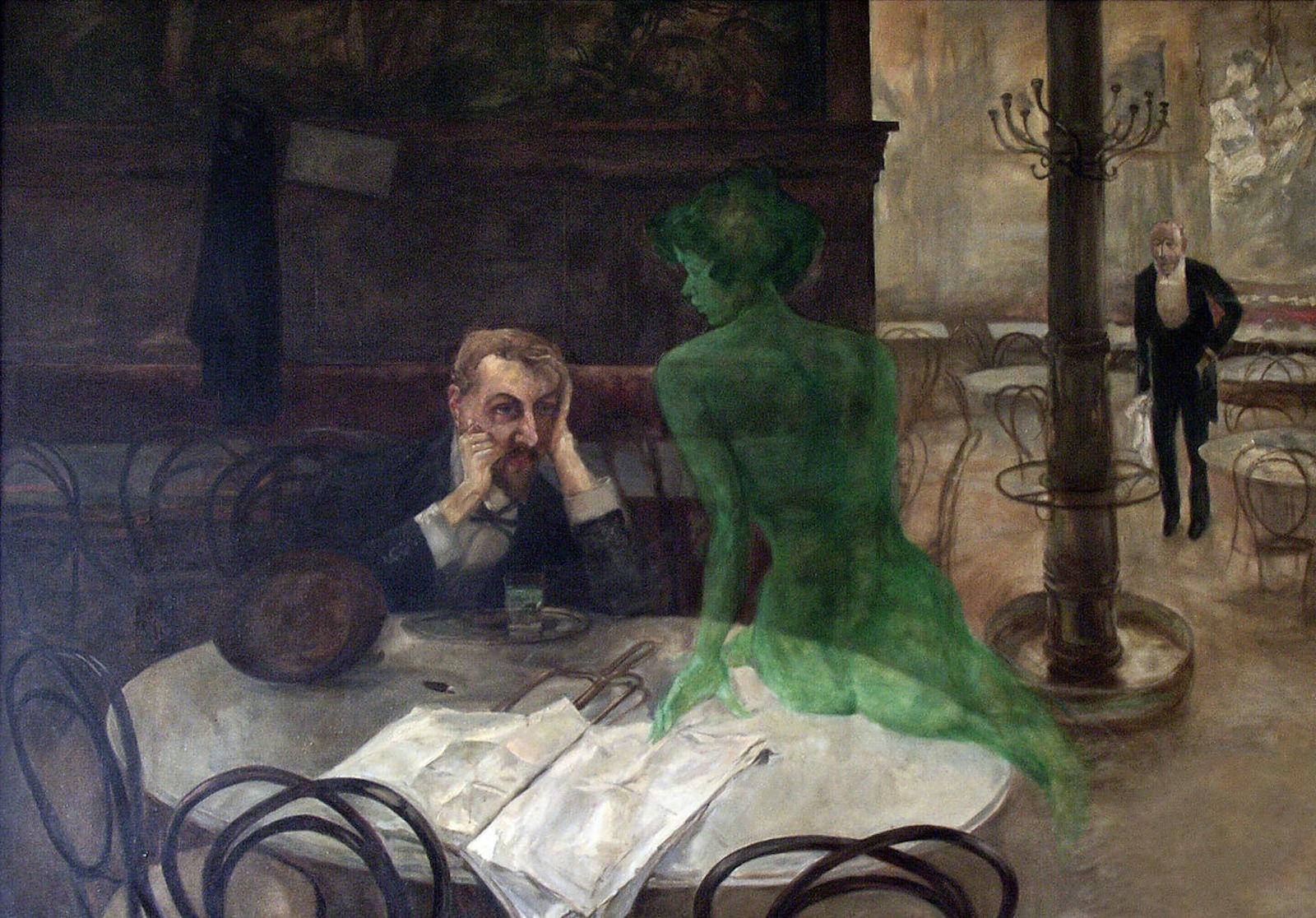

Edgar Degas, Viktor Oliva, Henri Toulouse-Lautrec, and Vincent Van Gogh—among other artists—situated the bitter green spirit as their muse or featured it as a prop in their works. While Degas’ L’Absinthe and Oliva’s The Absinthe Drinker focus on the melancholy and isolation of Absinthe indulgence, Toulouse-Lautrec—who famously stashed the spirit in his hollowed-out cane—celebrated the fairy within his art and personal relationships.

Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec, At the Moulin Rouge, 1892 - 95. Oil on Canvas. The Art Institute of Chicago.

In many cultures, green is the color of rebirth and prosperity, a harbinger of life and spring. However, placed within the context of the nineteenth century, green begins to represent the dualities of inspiration and melancholia, health and sickness, and life and death. This trend was due to the rising popularity of the spirit Absinthe and the arsenical pigments of Scheel’s Green and Paris Green. Paintings, prints, and fashion of the time reveal how this alluring—yet insidious—color took the century by storm and left a slew of debauchery and death in its wake.

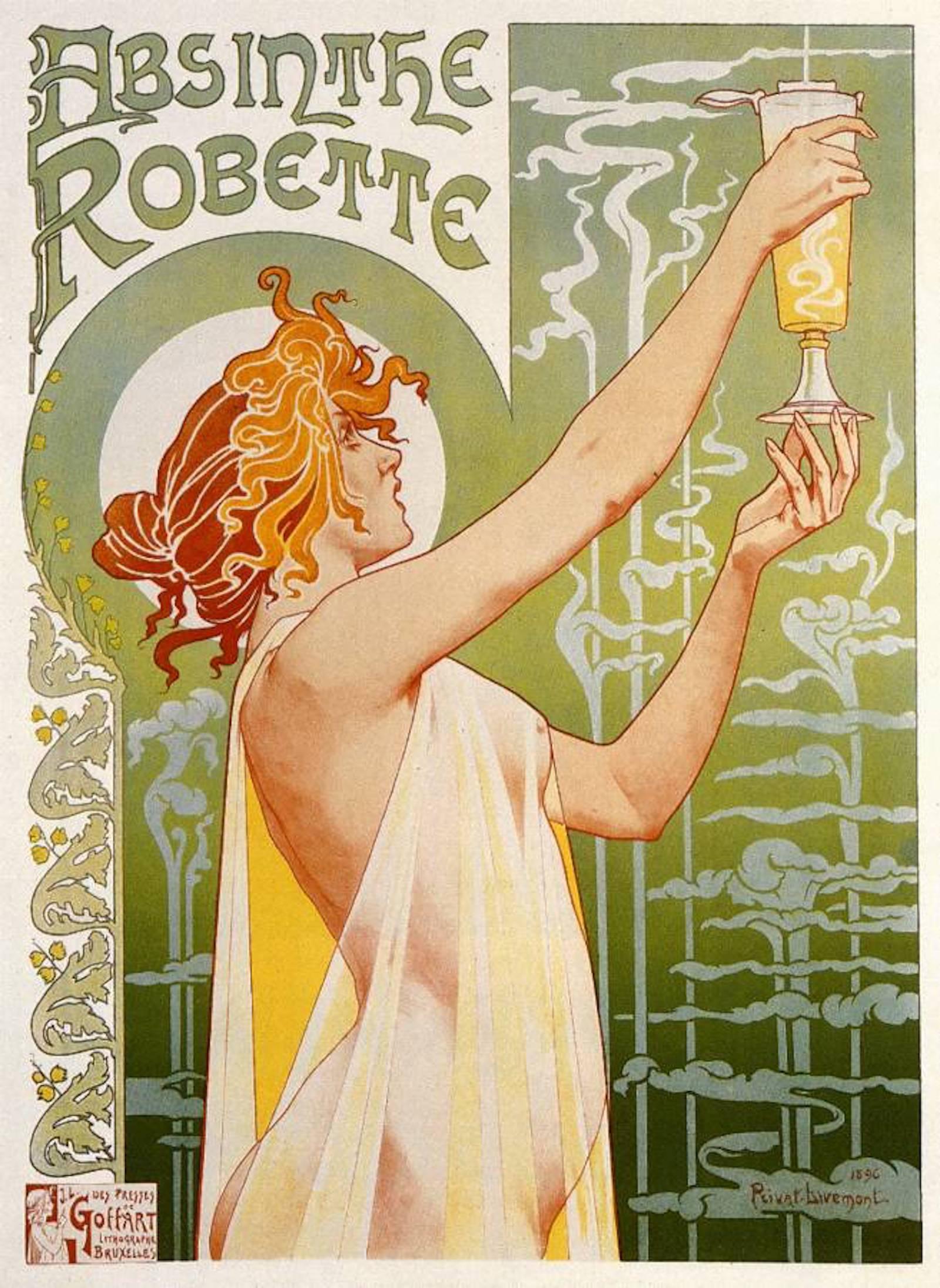

The favored drink of artists, Absinthe, was advertised as a cure-all elixir by French physician Pierre Ordinaire in the 1790s; although Wormwood, the active ingredient in the liquor, had been known for centuries for its powerful medicinal properties. Within a short time La Fée Verte, or The Green Fairy, became synonymous with the bohemian lifestyle and café culture of La Belle Époque.

Viktor Oliva, The Absinthe Drinker, 1901.

Highlighting phases of euphoria, Toulouse-Lautrec’s oeuvre captures all facets of the green hour—the nineteenth century Parisian Happy Hour—and the subsequent endeavors of the sprawling nightlife. Painting café scenes of his friends drinking, dancers and patrons of the Moulin Rouge, or sex workers, Toulouse-Lautrec’s work is influenced by the spirit and color of the fairy.

As the Temperance Movement began successfully smothering the exuberance and overindulgence of La Belle Époque, consumption and distribution of Absinthe became illegal in several countries including France, Canada, and the United States.

Green Silk Dress, Circa 1870.

While Absinthe ruled the social scene, the fascination with green also boomed in fashion and décor throughout the century with the creation of the striking inorganic—and highly toxic—pigments of Scheel’s Green and Paris Green. The dangers of these cupric arsenite pigments and dyes were known early in their use due to the serious injuries of laborers and craftspeople (as noted in the Accidents Caused by Arsenic Green medical print) and a more rapid onset of death in consumers of products made with the pigments. Despite this, the deep emerald greens continued to be used for an array of items including artificial flowers, fabric dye, wallpaper, and children's toys.

P. Lackerbauer, Accidents Caused by Arsenic Green, 1859.

Though regulations such as Britain's Control of Poisons Bill (1851) and Arsenic Act (1868) protected individuals, it did not limit large-scale industrial use of arsenic within consumer products. However, the responsibility does not solely fall on the patron; contemporary scientists and treaties argued that textile industries had access to equipment to detect arsenic but were more concerned with profit than maladies and death. With all that said, green was in vogue and people, from monarchs to the proletariat, were literally dying to get their hands on it.

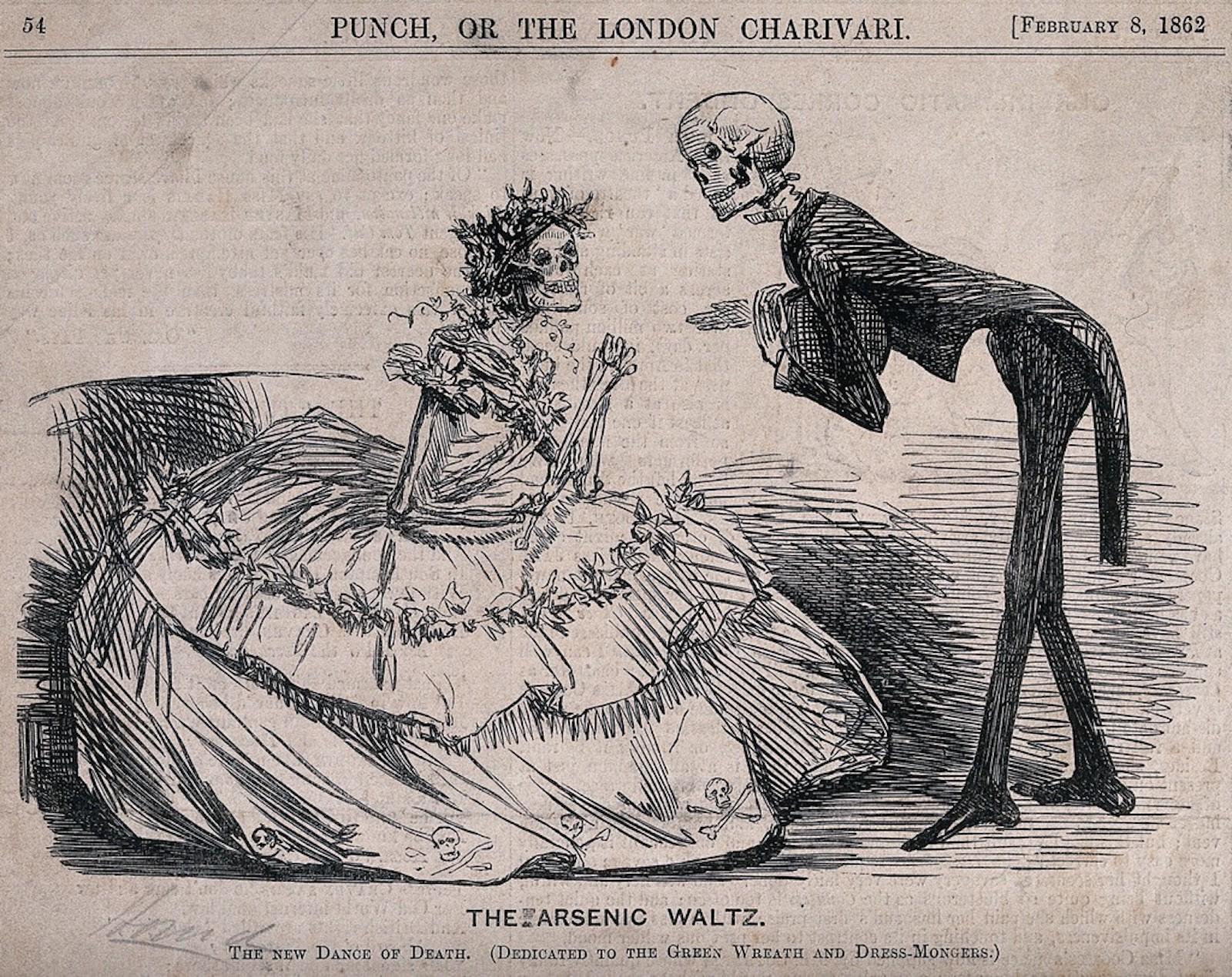

Journals satirized the fascination with the fashionable and lethal pigment, as seen in Punch’s cartoon The Arsenic Waltz or The New Dance of Death (Dedicated to the Green Wreath and Dress-Mongers). While not the primary focus of Georg Fredrich Kersting’s Genre painting Embroidery Woman, the vibrant glow of the green interior highlights the reach of the color, even in the most mundane of spaces at the beginning of the century.

The Arsenic Waltz, 1862. Etching.

As the continual negative press highlighted the dangers of Scheel’s and Paris Green—in addition to the natural ebb and flow of fashion—alternative non-toxic shades, such as viridian, eventually became more popular in the late nineteenth century.

As the unofficial color of the century, green was intertwined with various aspects of society. From beverages to fashion to décor, its hold on consumers rarely faltered throughout the period. The false narrative of joy and life associated with green brought the sinister dualities of the color to the limelight with rather deadly consequences.