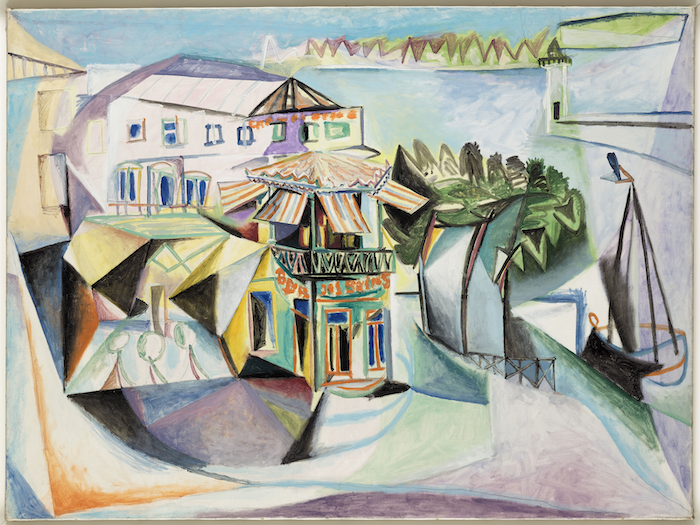

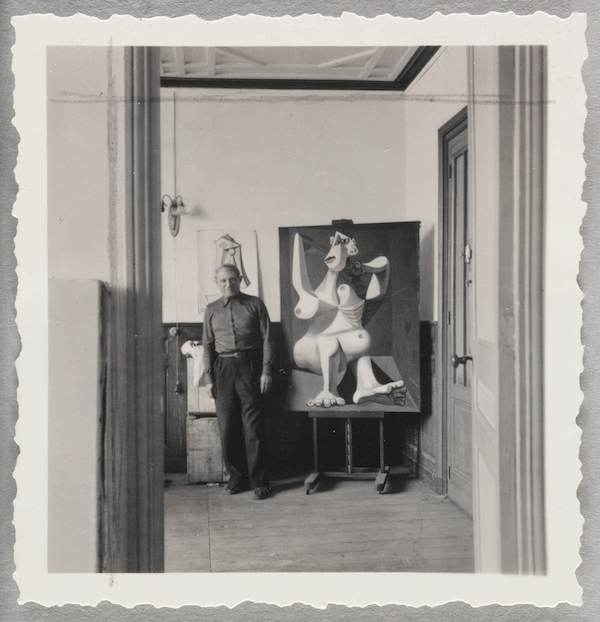

Over nine months, Picasso produced eight notebooks of drawings and poetry, and a handful of canvases, including the masterpiece Woman Dressing Her Hair. That painting, along with five other canvases and the sketchbooks, constitute the singular exhibition, Picasso: The Royan Sketchbooks, now at the Museo Picasso Málaga through May 3rd.

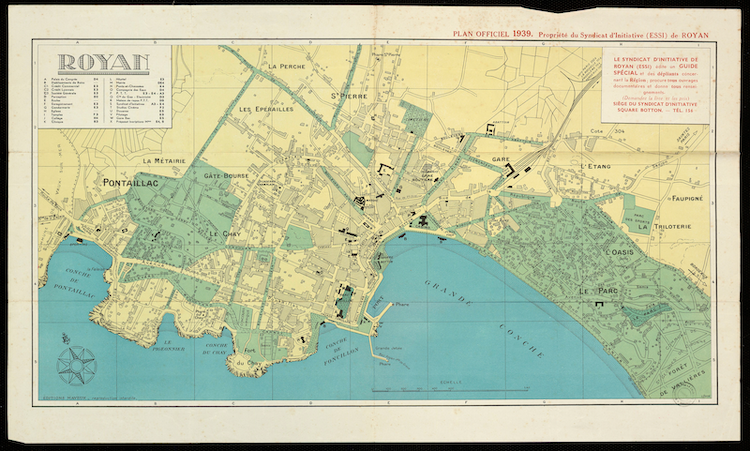

“At the end of the summer, 1939, there was a sense of panic among Picasso and his circle,” notes Marilyn McCully who co-curated the show with her partner Michael Raeburn. Since 1981, the pair have mounted numerous shows on the artist for museums in Paris, Istanbul, Amsterdam, Barcelona, Monte Carlo, and Antibes. “He went to Paris, checked out everything, got the closest people to him, his lover, his secretary, his mistress he’d already installed in Royan with their daughter, and took off for Royan. He focused on the female figure pretty much the whole time.”

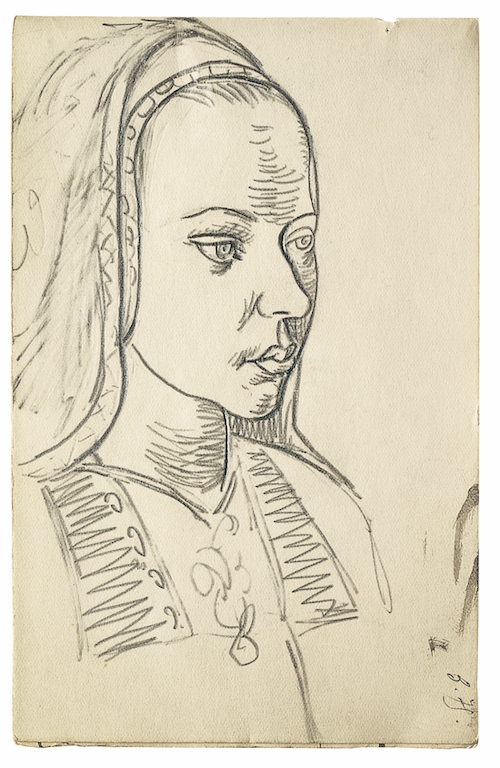

Although they remained married, Picasso’s relationship with Olga Khokhlova ended in 1935 after the birth of Maya, his daughter with Marie-Thérèse, who was frequently the subject of his work in the early 1930s, but is absent from the sketchbooks which instead focus on Dora Maar, whom he met in Paris in 1935.