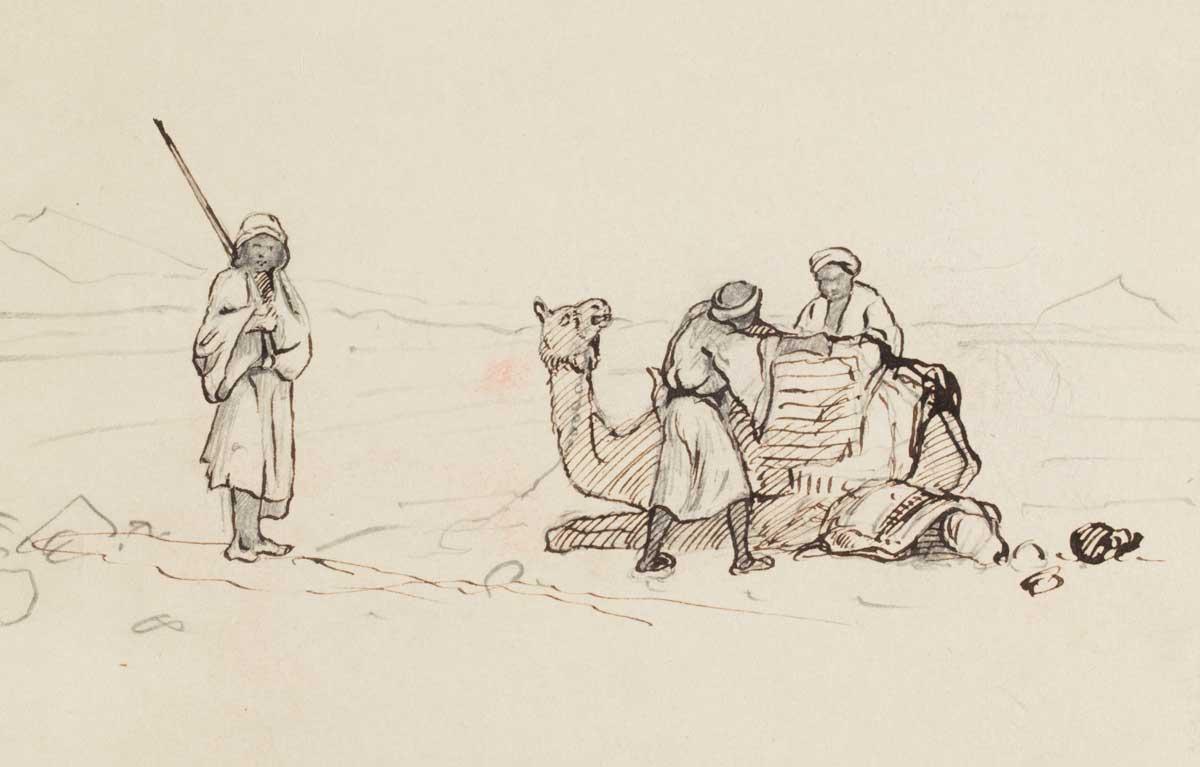

Petra had only recently been brought to Western attention by Swiss traveler Johann Ludwig Burckhardt when American artist Frederic Church made it a stop on his 18-month Middle East journey. When he returned to New York, he lushly depicted the approach to its Al-Khazneh temple — carved into a rosy sandstone cliff — from the darkness of the Siq gorge. He wrote in his diary that the ancient ruin was “shining as if by its own internal light.” Just visible in the gorge’s shadows are two Bedouin figures holding long rifles. The painting — El Khasné, Petra (1874) — has the feeling of a snapshot, but Church romanticized his memory of the site, including the Bedouins’ clothing. Although he got complete outfits as souvenirs, Churched mixed and matched pieces for his studio models to reflect his impression of the place.

“If you look more closely at the finished oil sketches that he did, unlike as was previously thought, they were not done onsite in the Middle East, they were done by his friend modeling for him in the studio and being dressed up by Church in a way that intentionally moves away from the authenticity of the costumes,” said Sean Sawyer, president of the Olana Partnership. “He knew what it should look like, but it wasn’t fulfilling the aesthetic needs that he had, so he decided to use a woman’s headscarf as a sash.” His Middle East paintings are “a place of fantasy.”

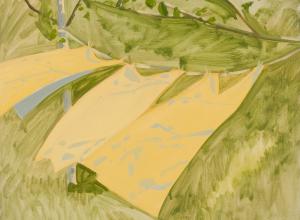

For the first time, the Middle Eastern clothes Church acquired are on public view in Costume & Custom: Middle Eastern Threads at Olana, on view through November 25 at the Olana State Historic Site in Hudson, New York. Olana is the Persian-style 1872 home that is a distillation of all that Church loved about Middle Eastern architecture. Islamic-inspired stencils adorn the walls; the shapes of windows and doors overlooking the Hudson River suggest mosque entrances. The sitting room where El Khasné, Petra hangs was based on the painting’s luminous hues.