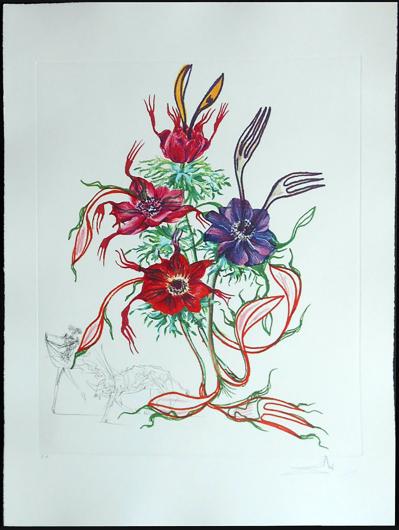

Dalí, Pisum sensuale (Cobea) from the FlorDalí series. 1968. Photolithograph and engraving.

Salvador Dalí’s oeuvre often brings to mind images of melting clocks, lobster telephones, or crucifixion depictions, but late in his career the artist also created three floral suites. At Denver Botanic Gardens through Aug. 22, 2021, Salvador Dalí: Gardens of the Mind exhibits nearly forty rarely seen works from FlorDalí (1968-1969) and Surrealist Flowers (1972).

The exhibition was organized by The Dalí Museum in St. Petersburg, FL, expanded from a show at the Marie Selby Botanical Gardens in Sarasota, FL. The works range from the whimsy of FlorDalí to the more mysterious, even violent FlorDalí - Les Fruits, according to Allison McCarthy, assistant curator at The Dalí Museum.

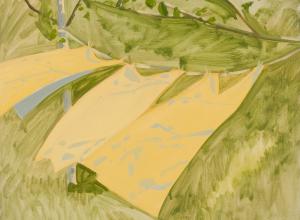

Denver Botanic Gardens Director of Exhibitions, Art & Learning Engagement and Head Curator of Art Lisa M.W. Eldred says that, although Dalí was not a gardener, his works often include elements of the natural world. Along with fruits and flowers, the artist painted and illustrated horses, elephants, bulls, giraffes, ants, mountains, seas, and trees. The Surrealist also frequently depicted wild places, landscapes reminiscent of the coast of his homeland in Spain.

“Despite his sensationalist celebrity lifestyle, Dalí’s works often returned to the untamed Catalonian beaches of his childhood,” according to The Dalí Museum Curator of Education Peter Tush. “The humorously composite plant creatures of FlorDalí grow in landscapes with topographies reminiscent of the craggy Spanish coast.”

One of the wildest places was Dalí’s own mind. “These unique and humorous plants sprouted from the fertile soil of the artist’s dreams and imagination,” explains Tush.

The Dalí Museum points out that, for his floral suites, the artist sometimes worked atop existing art. He painted and sketched some of his florals over botanical illustrations — an art form that emerged not long after movable type, with the first recorded examples dating back to the 1470s. For his FlorDalí suite, Dalí painted directly over original botanical prints from the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, altering their formality with intriguing and incongruous images.

“These fruit and flower prints playfully subvert the formal tradition of Western European botanical illustration with wild improvisations,” says Tush. Dalí also repurposed his own work, combining images from both the FlorDalí and FlorDalí - Les Fruits suites to create Flordalí I and Flordalí II.