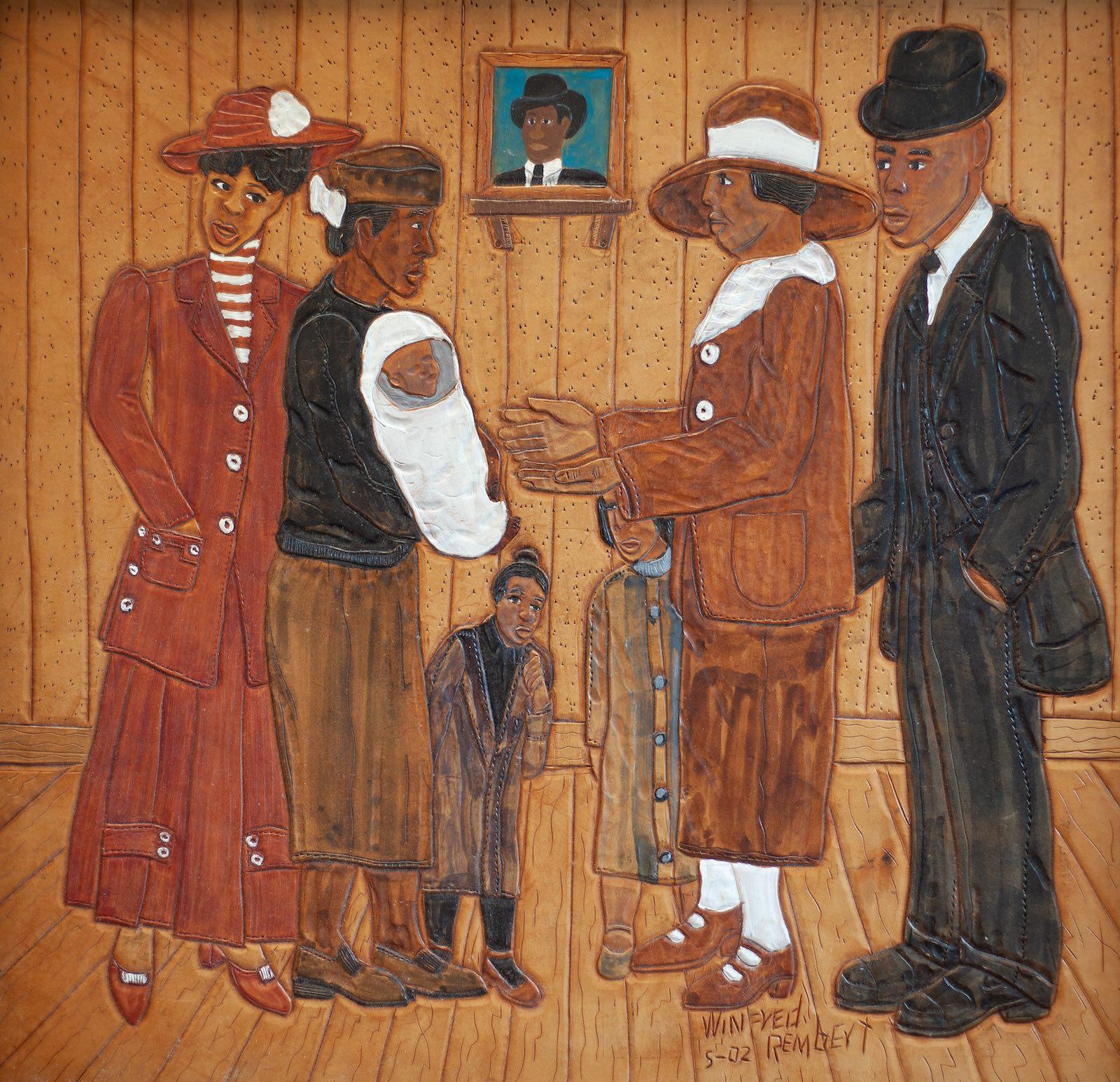

Winfred Rembert, 1945-2021, on view at Fort Gansevoort in New York City is a brutal but necessary show spread over three floors, tracing the chronology of Rembert’s life. The exhibit coincides with the publication of his memoir, Chasing Me To My Grave: An Artist’s Memoir Of The Jim Crow South, written with Erin I. Kelly, from which the wall text and captions are largely taken, ensuring that his voice and artistic vision is centered.

Carving the leather before painting over it makes the works almost three-dimensional, adding weight and texture to the scenes of Rembert's early life growing up in Georgia. It gives heft to the cotton bolls in Dinnertime in the Cotton Field (2011). Even in what should be a relaxing moment at the end of the day, the specter of the hard labor of picking cotton, which he did in his childhood and teen years sits over the scene like fog.