Throughout history, art has experienced its fair share of trends. Grisaille took artists by storm several centuries ago and, although the technique is unfamiliar to many now, monochromatic schemes continue to play a massive role in the art world.

Literally meaning “greyness” in French from the prefix gris, grisaille first emerged as uncolored glass frames within late-medieval stained glass. As a painting style, grisaille reached its peak prominence during the sixteenth century. The technique was initially limited to underpainting—a base layer of paint often used to give the top layers of oil paint a deeper sense of color unity—but it soon took on a life of its own.

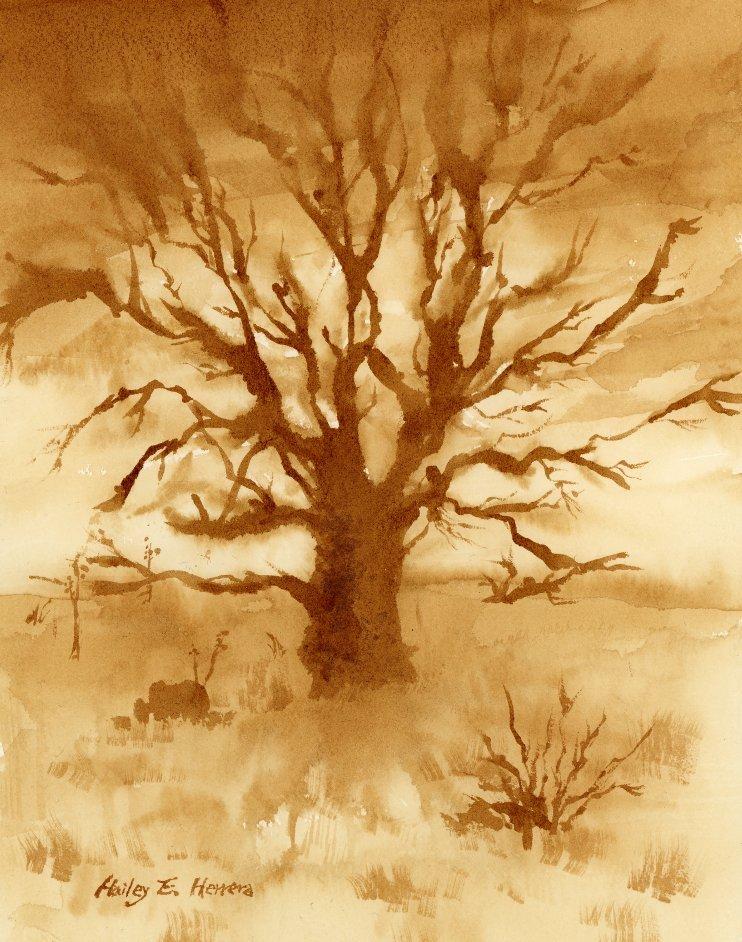

Grisaille evolved a benchmark of oil painting for several crucial reasons. The use of color in pictures led to many tedious obstacles. Artists desired to spend less time, skill, and resources on their artwork. Consequently, the European painters sacrificed full-spectrum palettes to enhance the production process for their pieces. Grisaille essentially operates as a “middle man” technique for monochromatic portraits and landscapes. Although the method was less time-consuming, oil painters had additional justifications for utilizing the painting practice. The artists strongly appreciated the appearance of their work using grisaille. The underpainting procedure gave their pieces a three-dimensional effect, resembling sculptures. Today, grisaille manifests as an aesthetic admired by many art masters and students. The technique permits painters to pay close attention to brushwork and composition without concerning color.