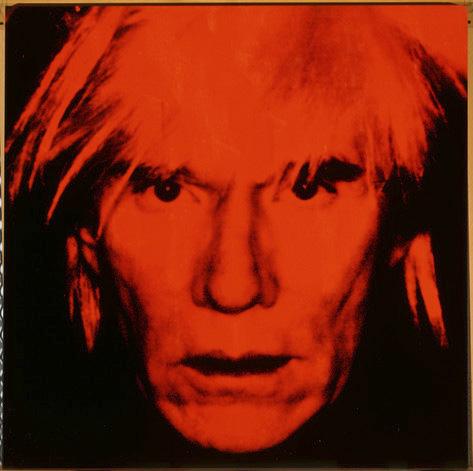

Warhol (1928-1987) was born in Pittsburgh to a family of working-class immigrants from Slovakia. He grew up skinny and badly-complected, but more pertinently Catholic and gay (conditions noticeably conjoined in art history) at a time when being either wasn’t welcome in mainstream America.

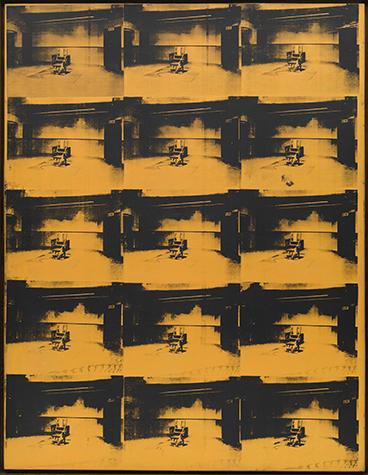

But, contrary to his image as an avatar of downtown cool, Warhol attended mass, underwrote his nephew’s priesthood studies, and served meals to the homeless. And, as his closest assistants could attest, he treated his studio, the Factory, as a kind of Vatican with himself as its passive-aggressive pope, presiding over a demimonde of dispossessed souls liable for excommunication if he tired of them.

Warhol was raised in the Byzantine Catholic Church, which, like the rest of Eastern Christianity, practiced the veneration of icons—a tradition that permeates Warhol’s appropriations of movie stars and soup cans. As a child, he was taken to church by his mother Julia. She remained a lodestar throughout his life, living with him in his Upper East Side manse for twenty years. One surprise of the show is that Julia made drawings of her own. These hang in a room devoted to her son’s earliest artistic efforts (including a plaster saint he colored in with paint when he was around twelve).