Americans can thank, in part, a landscape painter and a photographer for the founding of the expansive U.S. National Park Service (NPS), a governmental agency that manages all of the country’s national parks, most of its national monuments, and other historical and recreational properties.

President Woodrow Wilson signed the Organic Act on August 25, 1916, creating the NPS as a federal bureau in the Department of the Interior. Today, 424 National Parks sites cover more than 85 million acres in all 50 states, the District of Columbia and U.S. territories.

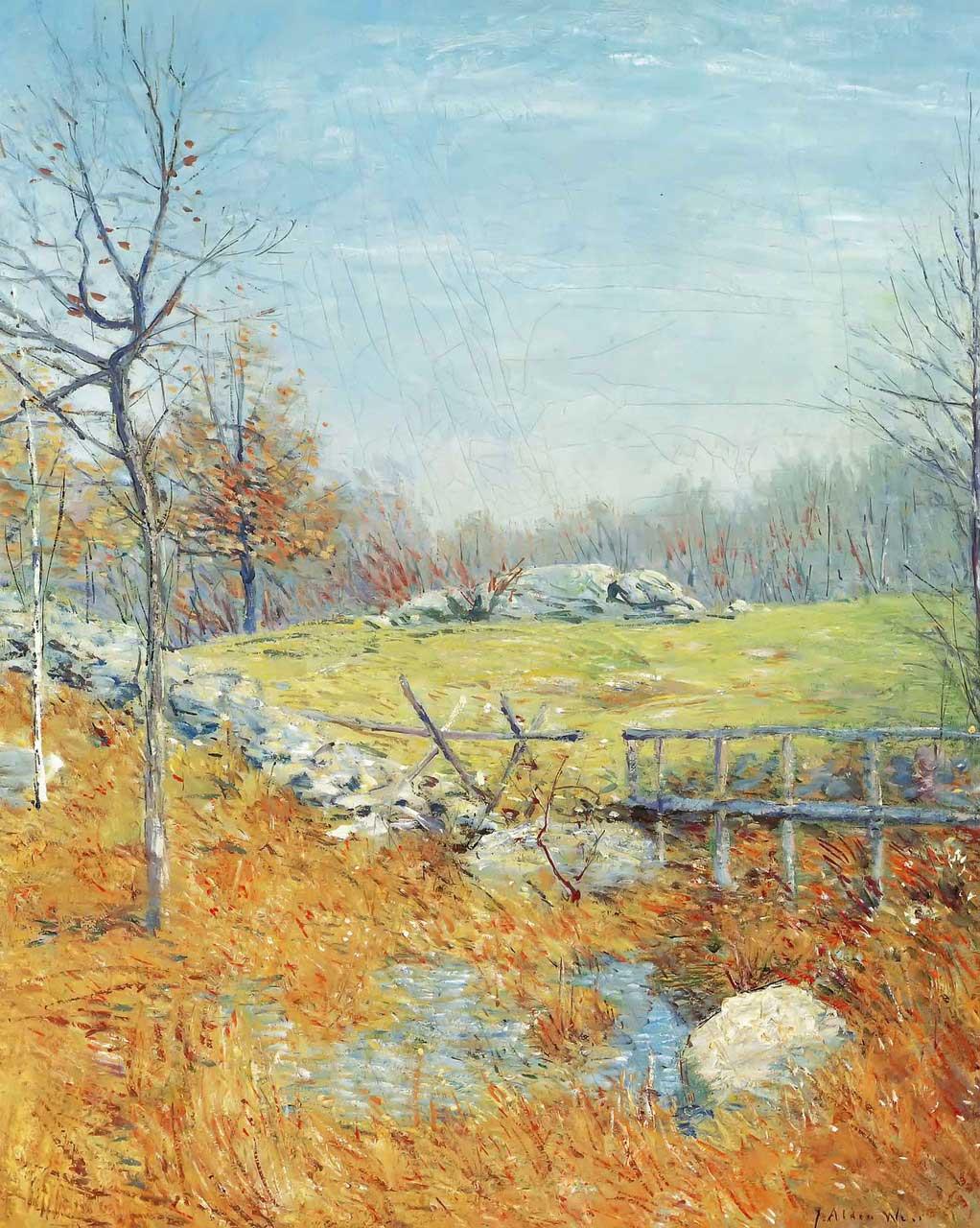

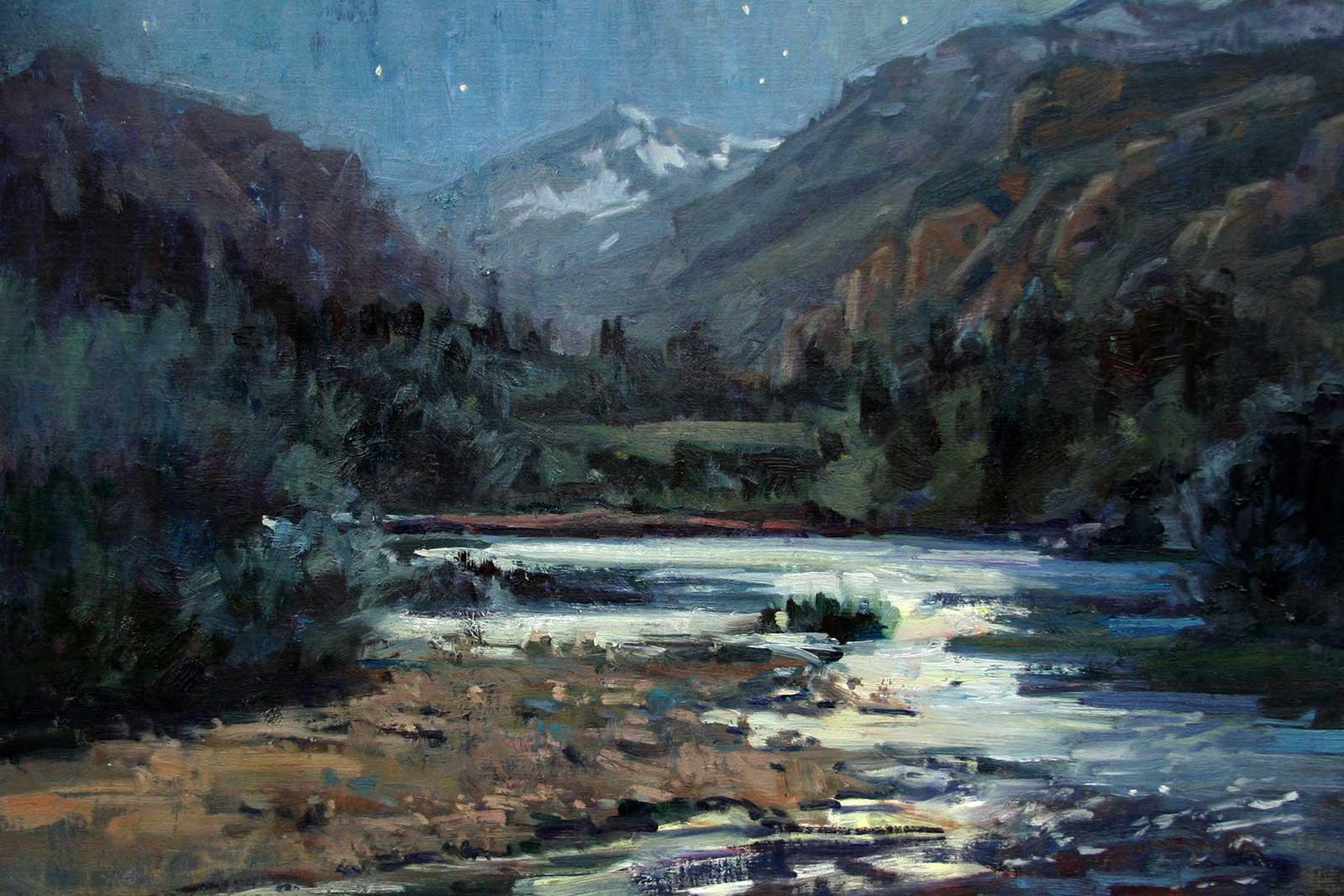

But the NPS got off the ground due to a series of paintings by Thomas Moran and photographs by William Henry Jackson. Invited to join a geological survey expedition in 1871, the painter and the photographer traveled to an area that would become Yellowstone National Park. They documented the landscape and brought back compelling images of majestic natural beauty in the American West, presenting sites unarguably worthy of the government’s protection.