The middle child of three, Bourgeois was born in Paris to the owners of an antique shop specializing in tapestries. In 1919, the family decamped to a suburb south of the city where they opened an atelier for tapestry restoration. That same year, Bourgeois' mother contracted the Spanish Flu and never fully recovered. An au pair was hired to look after the children, and soon, she and Bourgeois' father began a ten-year affair, with wife and mistress under the same roof, creating a veritable Hiroshima of psychological fallout that left a pall over Bourgeois' life.

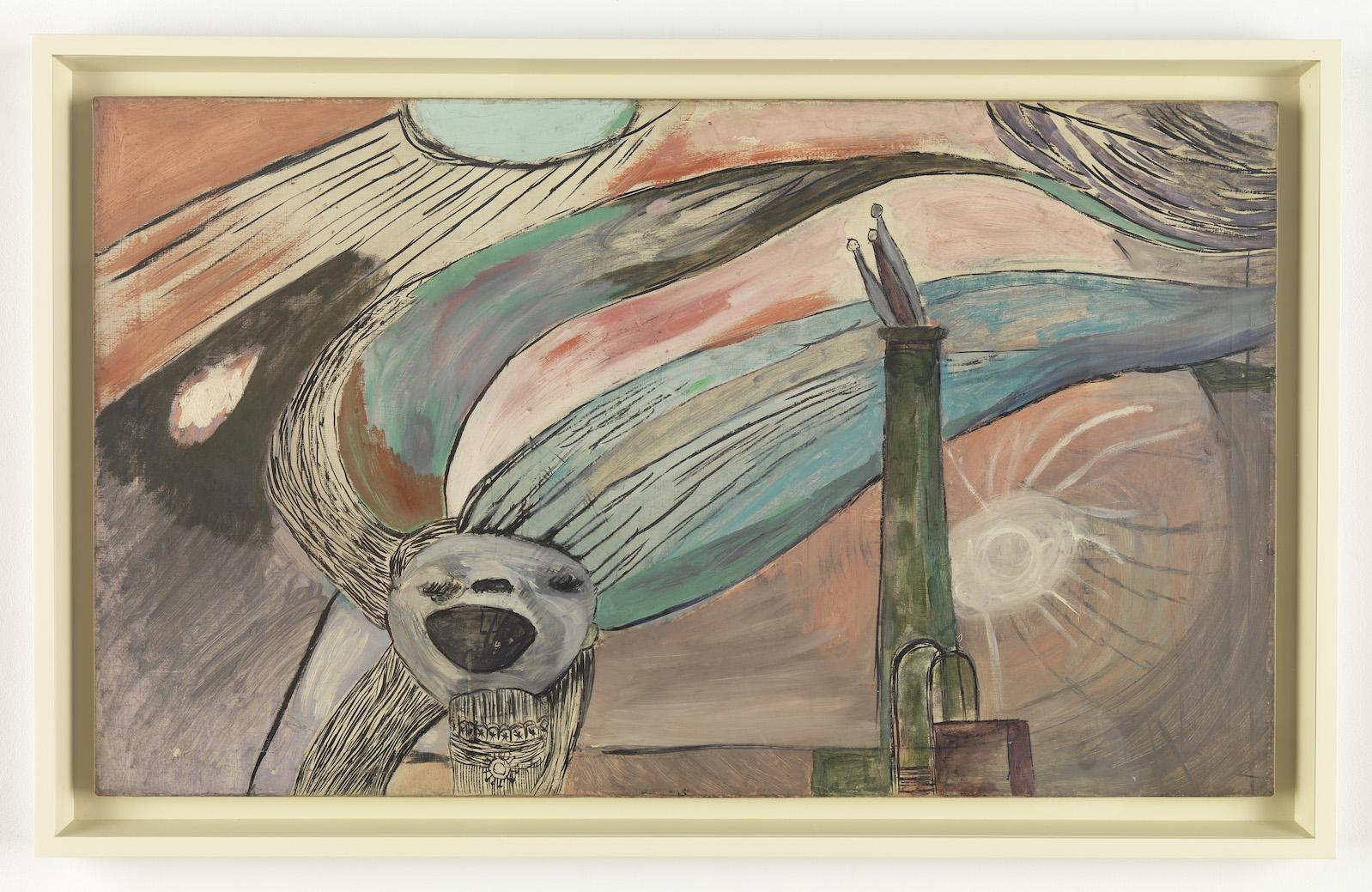

Bourgeois entered the Sorbonne in 1932 to pursue math but soon turned to art as a way of coping with persistent bouts of depression following her mother’s death. She attended classes at the École des beaux-arts and the Louvre. She also studied with the artist Fernand Léger, who advised Bourgeois that her real strengths lay in working three-dimensionally. He was certainly right, judging by the works on view: While fascinating and important to the artist’s story, none of them rise to the level of the sculptures that made her famous.