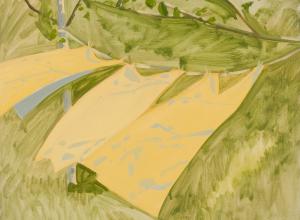

What art conservator Dale Kronkright discovered that day in 2000 would set off alarm bells in art museums around the world.

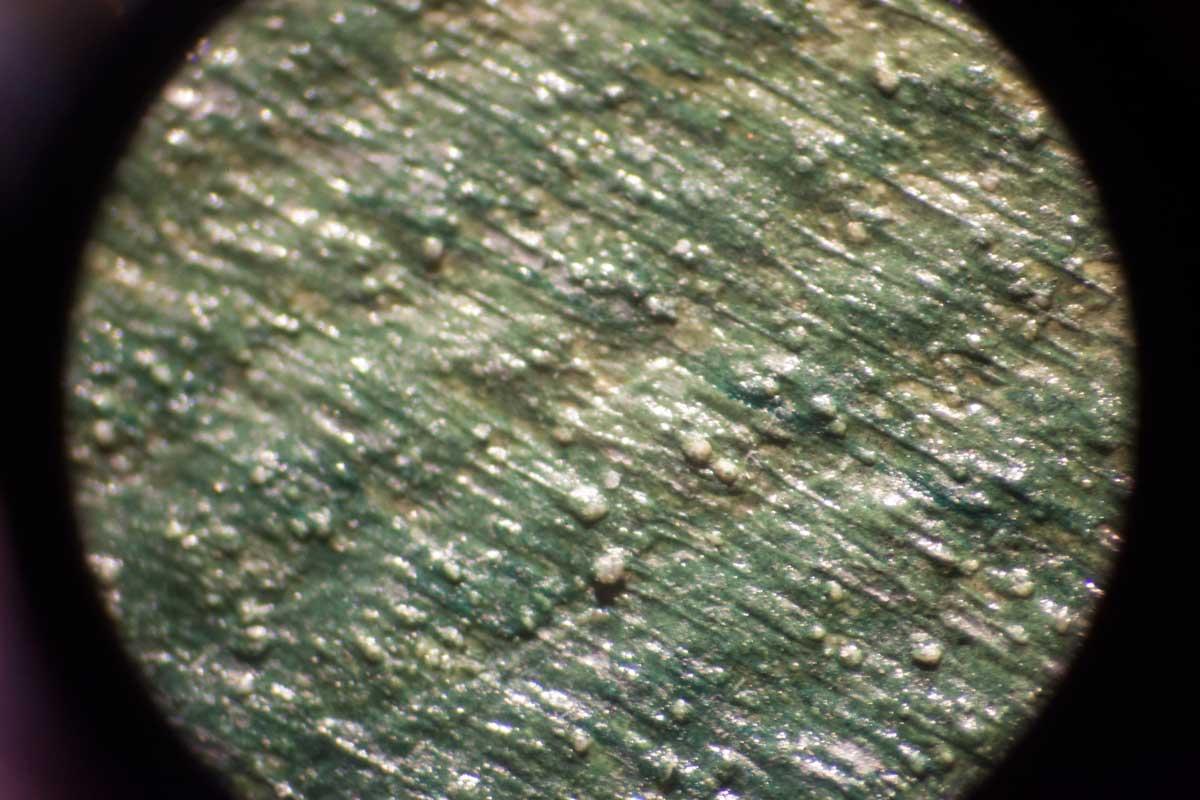

As head of Conservation for the Georgia O’Keeffe Museum in Santa Fe, New Mexico, the museum had only been open for three years, when he began to notice small grains in the paintings, not uniform in shape or appearance. As a result, these particular O’Keeffe paintings began to look darker, the colors less vibrant. “I asked some of the curators about it and they told me it was thought that O’Keeffe added sand to some of her paintings when she moved to the area,” he says.

But the grains were appearing in her earlier works as well, the ones O’Keeffe had painted while in New York. Kronkright also noticed that grains were appearing in the tacking edges of the painting, where the canvas had been stretched to meet the frame. It didn’t make sense that O’Keeffe would have added sand here, so Kronkright decided to take a closer look.

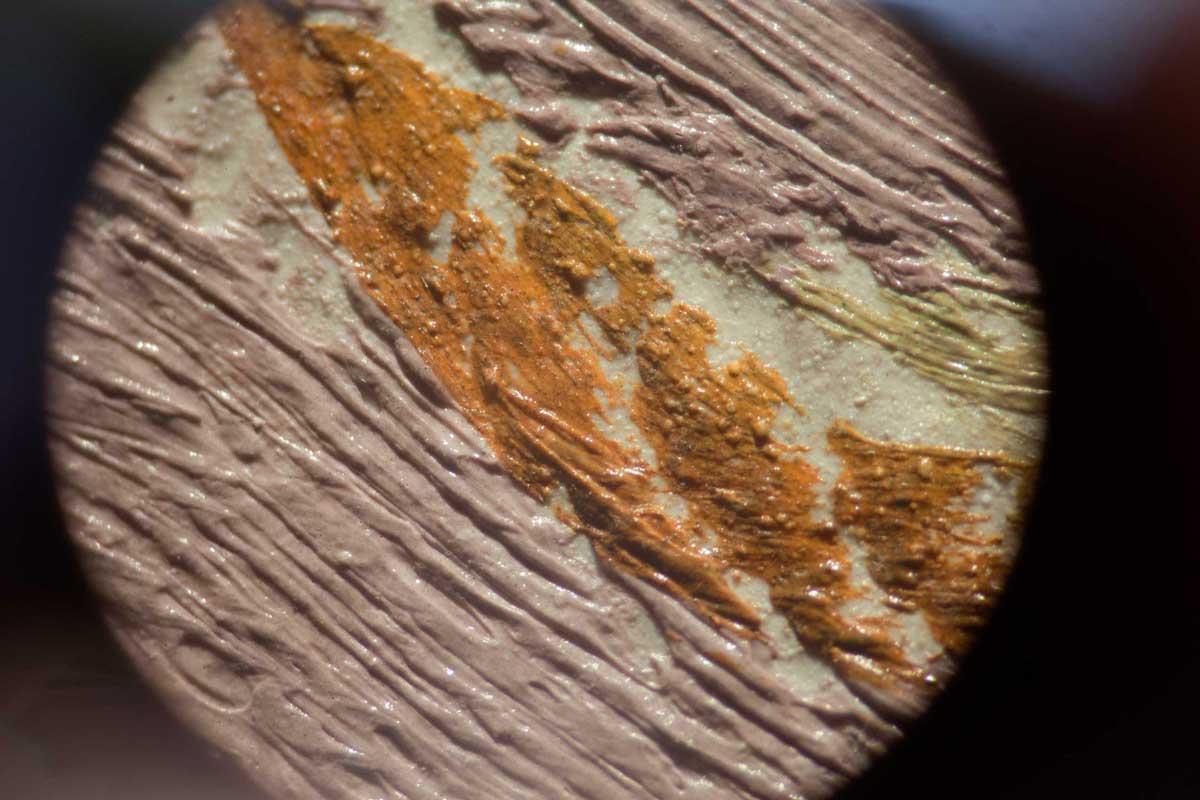

When he did, he found the grains were not grains at all, but, instead, tiny protrusions, which had begun to explode outward, or implode inward, giving the painting’s surface a blistered, pitted appearance—and there were sometimes thousands of these miniature eruptions all over the canvas.

So what, he wondered, was causing these protruding blisters?

It turns out it was the 20th-century materials—and 20th-century improvements that manufacturers had made to them—that were now causing a problem. At least two of these improvements had come together to create what turned out to be a “perfect storm” of destruction.