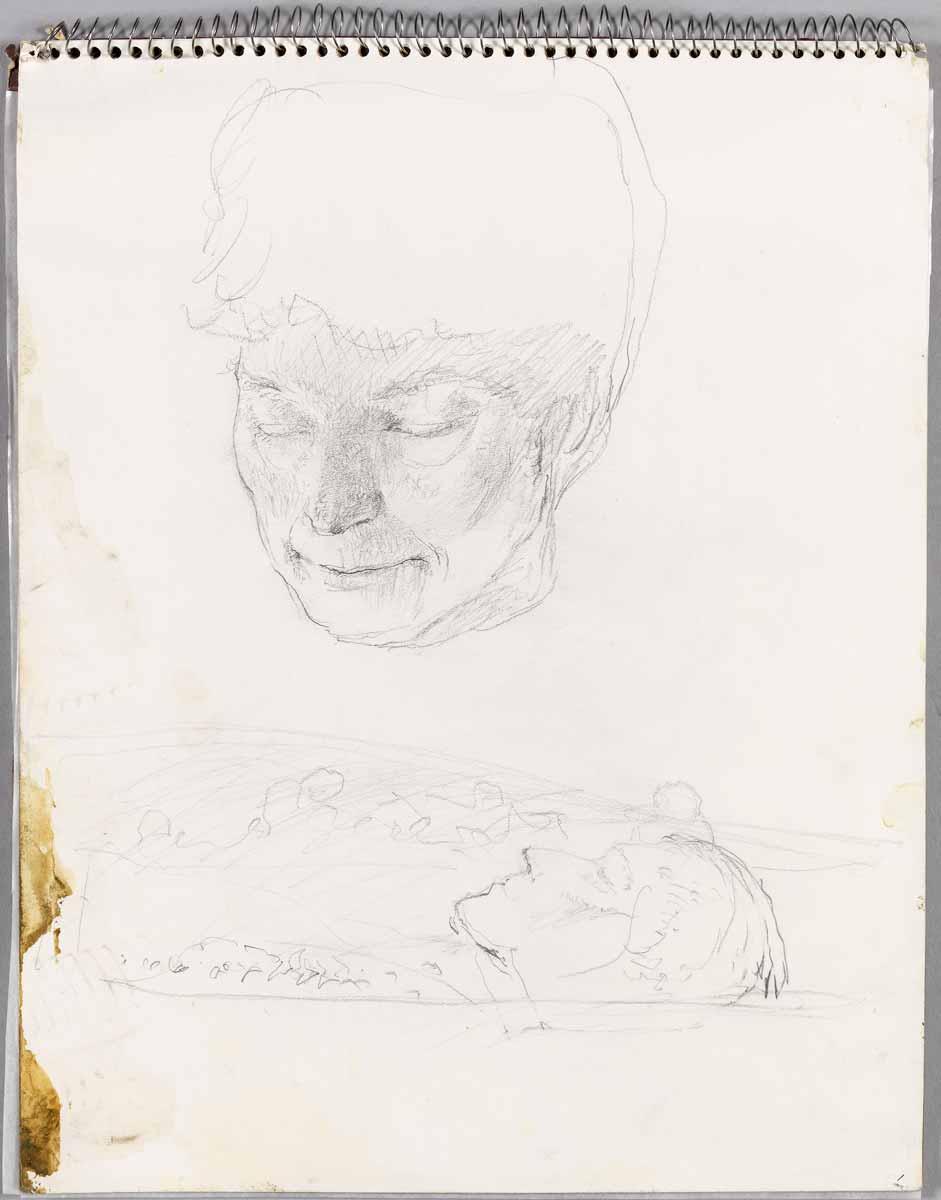

Although the “Funeral Group” drawings suggest Wyeth was exploring an idea for a larger work, he never completed one of his atmospheric tempera paintings based on the sketches. Instead, the drawings were left behind in the home of his friends in Chadds Ford, Pennsylvania. Only in 2018 were they rediscovered and connected to similar drawings in the Wyeth Foundation for American Art.

Now, at the Colby College Museum of Art in Waterville, Maine, through October 16, selections from the series are being shared with the public for the first time in Andrew Wyeth: Life and Death. The exhibition includes contextual art by Wyeth as well as pieces by other artists who have meditated on their mortality. A catalogue of the same name, co-published with Delmonico Books, further examines the drawings through recent research.

As Colby College recently acquired two islands off the coast of Maine where Andrew and Betsy Wyeth lived and worked, the exhibition adds to their engagement with his creative practice.

“The rediscovery of the ‘Funeral Group’ helps us understand how Wyeth’s thinking about death and its representation evolved over his long career, particularly through the genre of self-portraiture,” says Tanya Sheehan, curator of the exhibition and a professor of art at Colby College. “The series also shows us how the artist was imagining his legacy and his relationship to his community as he approached the end of his life.”

Wyeth’s Christina’s World (1948) is one of the most recognizable works of twentieth-century American art, yet the artist remains a polarizing and enigmatic figure who adhered to a pastoral realism amidst the rise of abstraction. In the rural settings that pervades his work, death is often a haunting presence. Until his own death in 2009, health issues punctuated Wyeth’s life, including a 1951 surgery to treat a serious lung disease. A typically oblique self-portrait was made following the operation called Trodden Weed, showing only Wyeth’s legs, clad in his father’s boots, walking on the desiccated grass of winter. His self-portrait Dr. Syn (1981), meanwhile, portrays a seated skeleton dressed in a blue military coat while Breakup (1994) pictures the artist’s own hands desperately reaching through the broken ice.