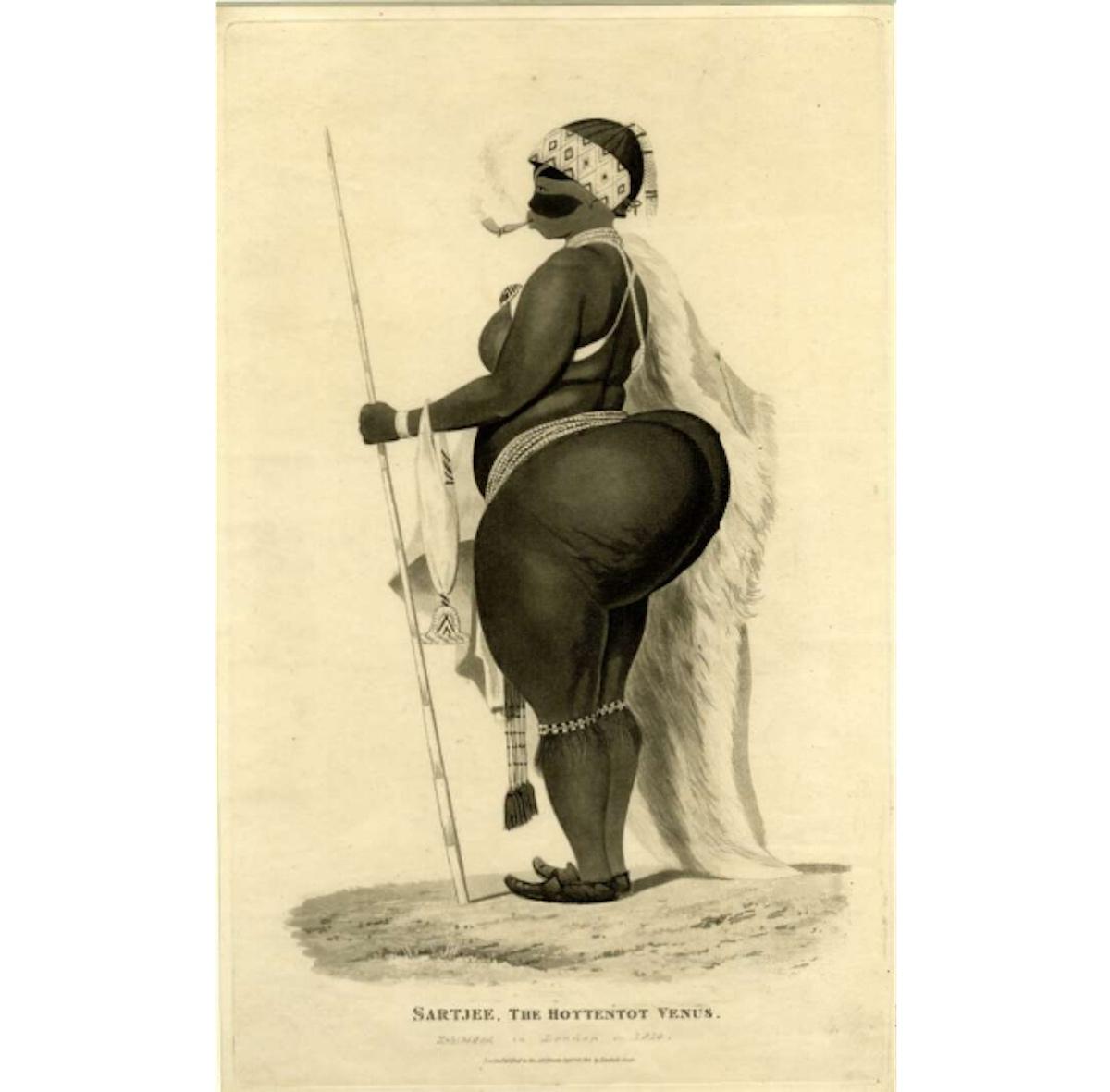

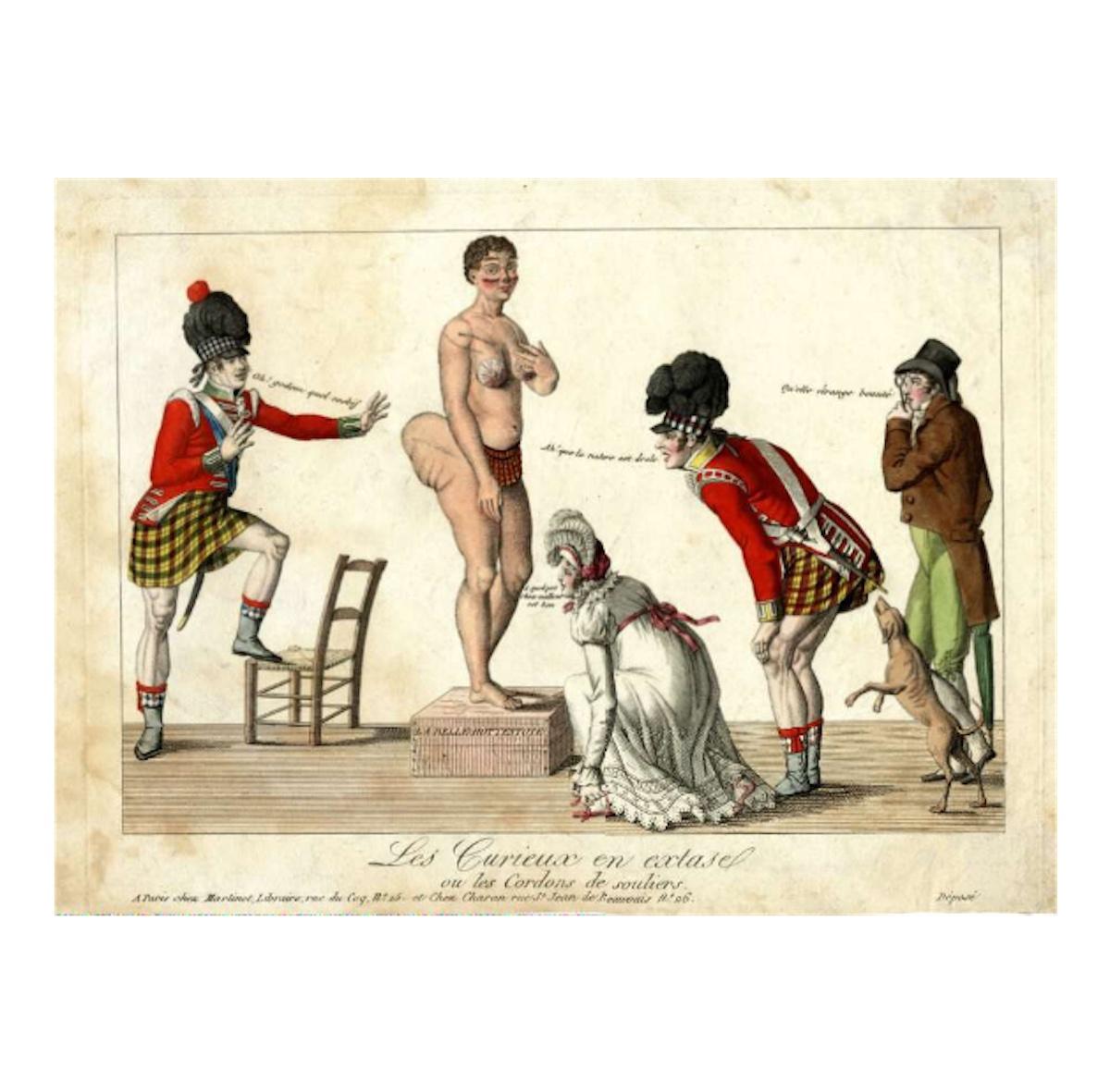

Sociology scholar Zine Magubane asserts that society’s initial reaction to Baartman was not one of suspicion of the "other," but of social conditioning that encourages the distrust and disgust of blackness. The public’s response to Baartman at her shows was that of disgust and fascination, but Magubane claims that there is more to this response than physical difference. The Hottentot apron was a large reason, as well as her extended buttocks, that Baartman was deemed a medical spectacle. The Hottentot apron was a practice of elongating the labia of khoikhoi women. These elongated labia fascinated scientists of the time and created a spectacle of Baartman as being both male and female.

James Tissot, The Ball on Shipboard, 1874. Oil on canvas

The bustle was a fashion accessory in Victorian Europe's upper-class society throughout the nineteenth century. In its function, it replaced the hoop skirt to provide wealthy women with a desirable figure that exaggerated the curvature of the buttocks. Despite its integration into couture fashion during the period, the origins of this accessory have an arguably complex history that is rooted in the exploitation of Black women. Specifically, the bustle is arguably directly inspired by Black body types. Through the repulsion and desire of Black women in European society, the bustle quickly became a staple among the elite.

Saartjie Baartman (1789-1815) was a South African woman from the Khoikhoi tribe. Baartman was employed by William Dunlop and Henrik Cesars to work as an indentured servant. During her servitude, she was put on display at “freak shows” across Paris and London. Later in life, she became associated with an animal exhibitor, whom scholars believe forced Baartman into prostitution. At the age of twenty-six, Baartman died due to an inflammatory disease believed to be syphilis. During her lifetime, big bottoms were deemed desirable for women in Victorian Europe, so Baartman’s figure was admired and envied by audiences. After her death, Baartman’s body remained on display at a Parisian ethnographic museum until 1974.

Georges Seurat, A Sunday on La Grande Jatte, 1884-1889. Oil on canvas, 81.7 × 121.25 in (207.6 × 308 cm), Art Institute of Chicago, Chicago, Illinois

During the time of Baartman’s indentured servitude and shows, Baartman inherently reflected social issues of the time back to the viewer: liberty, the right to property, and slavery. Although Hottentots were legally free, there were laws at the time that subjugated them to be laborers. While some people saw Baartman as their physical antithesis, others saw her as the personification of slavery, and how to work around it in the name of commerce and conquest. Magubane argues that the white supremacy at play in Baartman’s servitude to Cesars was not just oppression based on race, but based on her mental capacity, culture, physical “abnormalities,” and other differences. Although Baartman is one of the most noted exhibited individuals, there were thousands of other people exhibited at this time due to their physicality.

Jean-Georges Béraud, The Box by the Stalls, 1883. Oil on canvas, Carnavalet Museum, Paris.

Originally made of boning and padding, an association between fatness and sensuality is essential to the function of the bustle. The bustle represented both a private truth of sensuality and a public acceptability of representation, according to scholar Casey Finch. In this way, fatness was acceptable in the private context of sex but unacceptable in the public sphere. The bustle originated from the perceived sensuality of Baartman through the male gaze. This gaze is exhibited in Jean-Georges Béraud’s The Box by the Stalls (1883), representing a reformation of ideas regarding curvaceousness when associated with white wealth.

Once a marker of wealth and sophistication, the bustle’s problematic history further contextualizes the historical appropriation of Black phenotypes and culture in the colonized world. Despite the evolution of fashion since the nineteenth century, it can be argued that the recent resurgence of the bustle in a Fall 2014 Christian Dior fashion show coincides with the prevalence of "black-fishing" on social media, exhibited by celebrities such as Kim Kardashian, Kylie Jenner, and Iggy Azalea who have been consistently criticized for their appropriation of Black phenotypes. Despite this, the bustle serves as a reminder of the atrocities of slavery and the exploitation of Black women.