Quite interestingly, the exhibition opens with examples from two Old Masters, including a copy of Albrecht Dürer’s Martyrdom of Ten Thousand Christians, where the painter appears as a character, and a series of self-portraits by Rembrandt. The former was representative of a shift in the self-perception of the artist, which evolved from “craftsman” into “genius”. Rembrandt was keenly focused on drawing himself and, throughout his life, he produced more than 80 self-portraits, in which the appeared in different clothes, but with the focus always on his face. The exhibition the abruptly jumps to 20th-century self-portraiture.

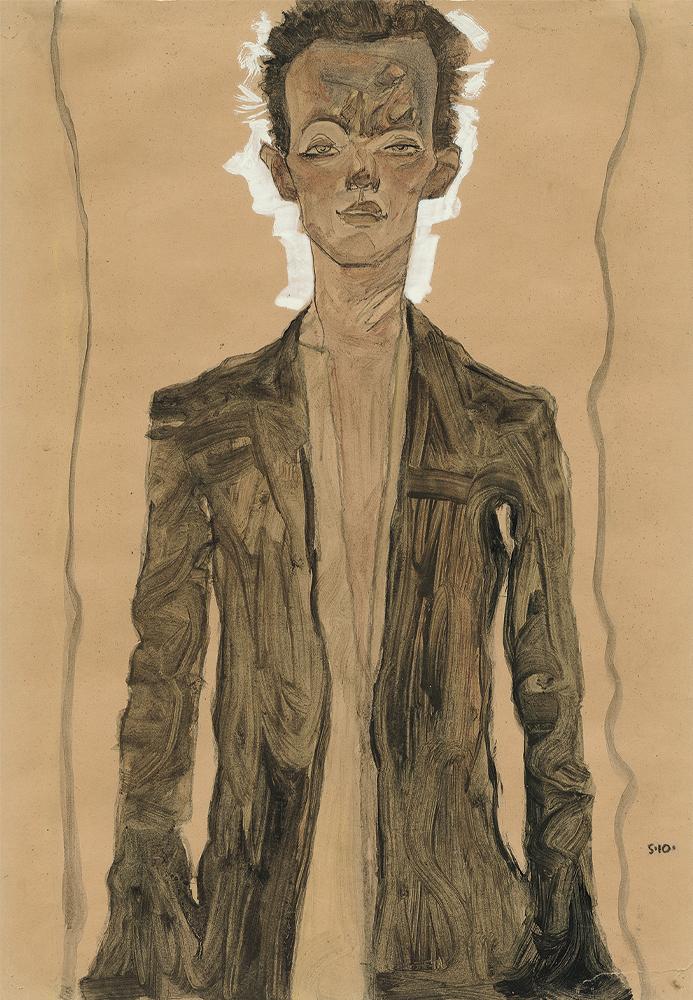

Egon Schiele is greatly represented in the show, and viewers can see how he toyed with the genre first in the relatively conservative Self-Portrait from 1906, which is a somewhat realistic work with watercolor and gouache on paper. Then, his triple self-portrait from 1913, sketch-like in appearance, challenges the ideas surrounding the genre by juxtaposing three different versions of himself, if not straight-up “selves.” His Man and Woman (or Lovers) from 1914 defies the conventions of two genres, traditional self-portraiture and the nude, by painting the male figure as staring defiantly at the viewer, and by having the female nude with her back turned to them. Similarly to Schiele, Oskar Kokoschka used self-portraiture to showcase his many “selves.” In The Painter And His Model (1923), he portrays himself in the act of painting a younger version of himself, referencing an artwork from 1910. In both of those portraits, he depicts himself as wounded, which served as a metaphor of society wounding the artist—he was an outcast. The ‘painter’ in the painting, however, represents his current self, a professor at Dresden whose fortunes changed for the best after the war.

![DEl Kathryn Barton [Australian b. 1972] the more than human love , 2025 Acrylic on French linen 78 3/4 x 137 3/4 inches 200 x 350 cm Framed dimensions: 79 7/8 x 139 inches 203 x 353 cm](/sites/default/files/styles/image_5_column/public/ab15211bartonthe-more-human-lovelg.jpg?itok=wW_Qrve3)