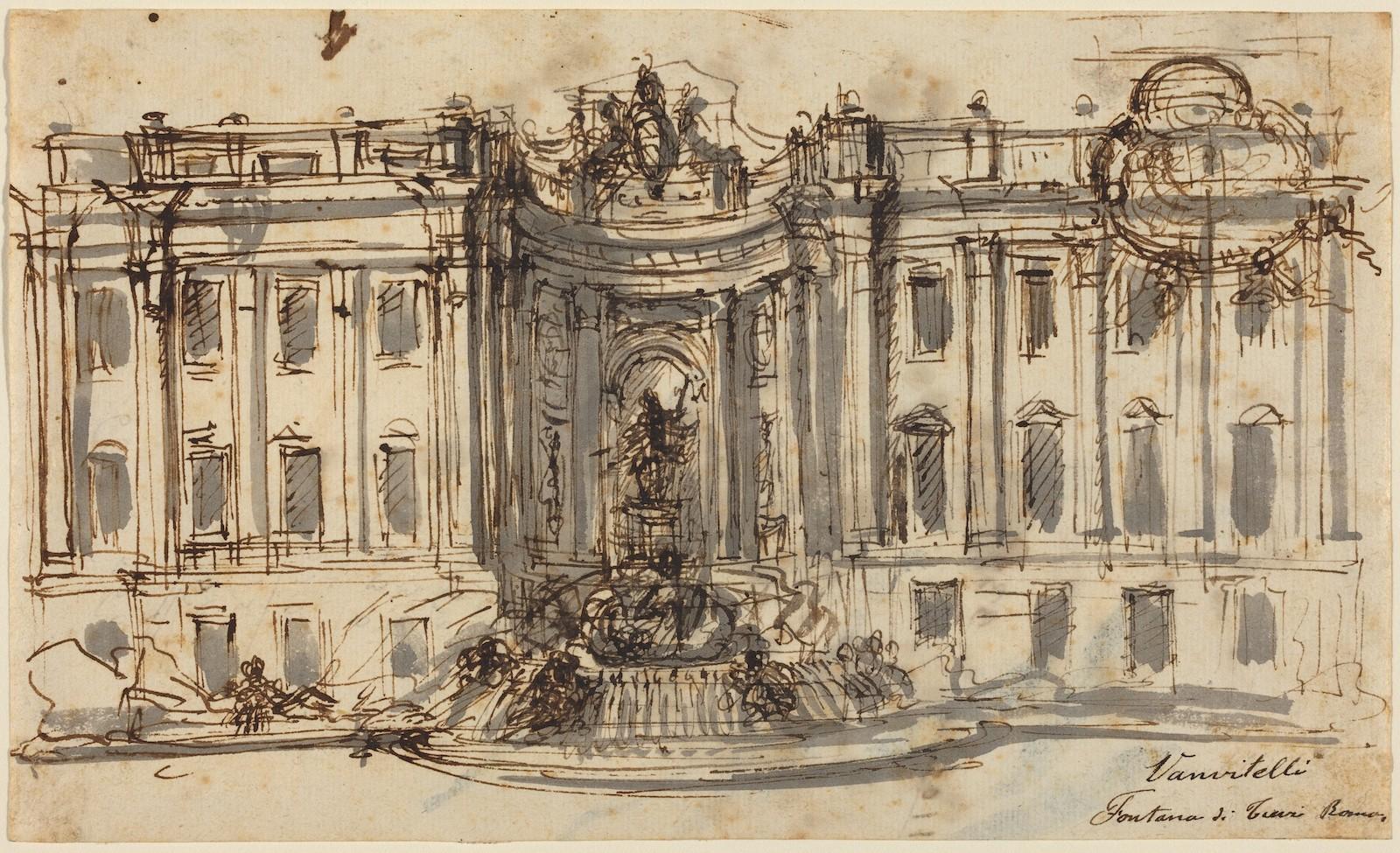

In 1730, Pope Clement XII (1730-1740) held a contest for the design of the Trevi Fountain, seeking to strengthen his Papal legacy. Salvi, who was born and died in Rome, initially lost to Florentine architect and mathematician Alessandro Galilei (1691-1737). But there was such public outcry over Galilei’s Florence origins, that subsequent calls for Salvi to do the Roman fountain instead led to Salvi’s ultimate selection as the contest winner. He would spend the rest of his life working on the fountain (he died in 1751), leaving four sculptors to finish its ornamentation with Pannini overseeing the project as architect until its completion in 1762.

The fountain’s location is integral to its functionality as a public space, according to Roman art and archaeology scholar John Pinto. Pinto asserts that the Piazza di Trevi, an intersection of three major Roman streets forming a trivium, is likely where the fountain got its name. Pinto claims further that these streets follow the path of ancient Roman roads, signifying the fountain’s ties to Roman antiquity.