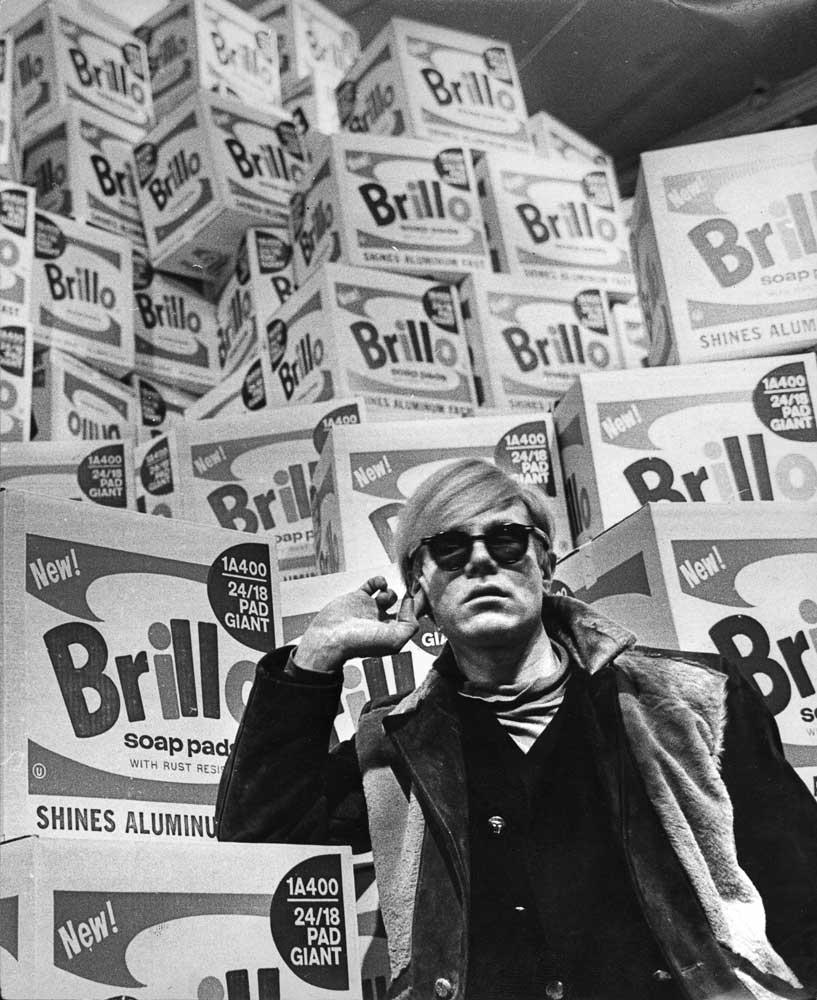

Andy Warhol’s first solo exhibition at a museum was not, as one might presume, in New York. It was at the Moderna Museet in Stockholm, in 1968, and it laid down the roots for a scandal involving fake Warhol Brillo Boxes that would come back to haunt the Swedish museum decades later.

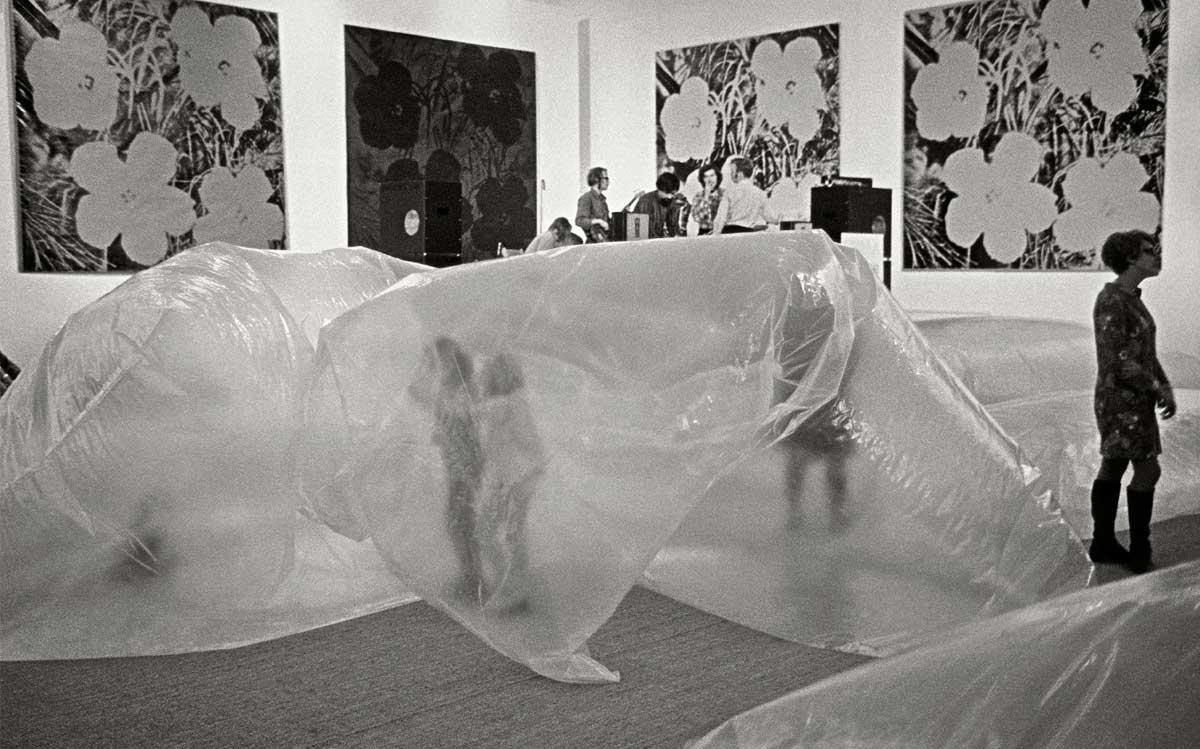

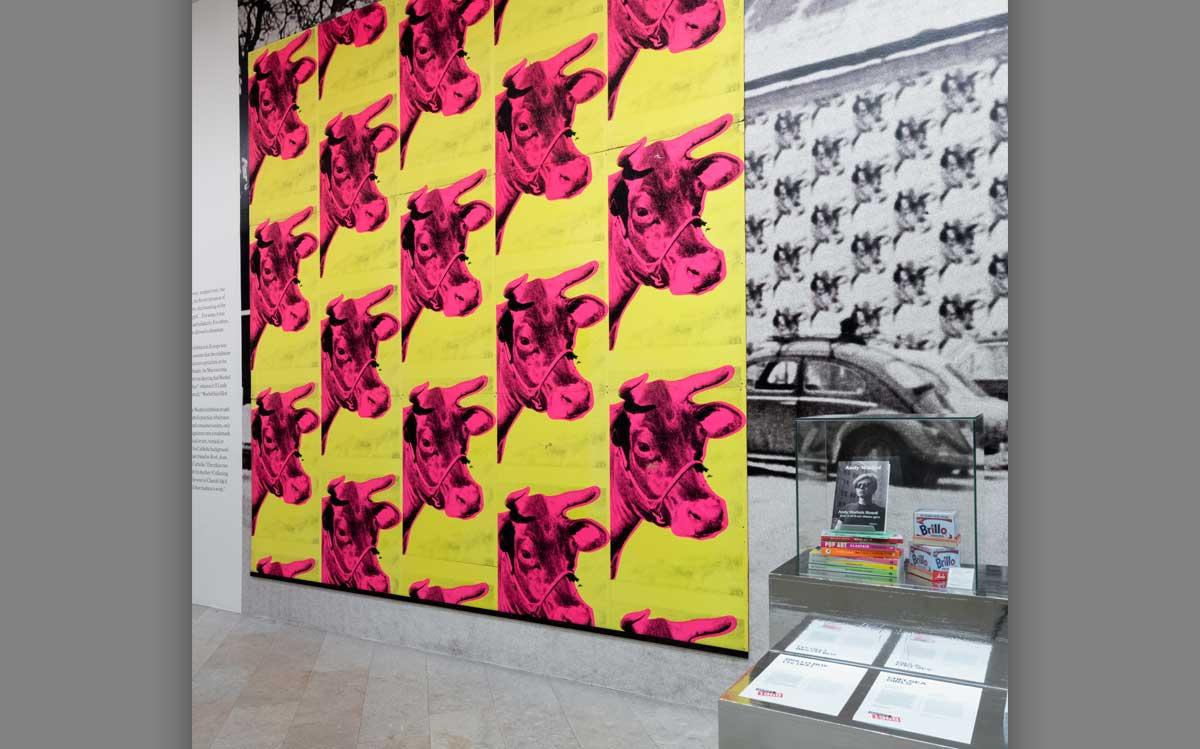

In 2018, the Moderna Museet revisited the 1968 show–and came clean about those Brillo boxes–in an exhibition called Warhol 1968. Alongside both fake and original Brillo boxes, the show features iconic works Cow Wallpaper, Marilyn in Black and White, and Ten-Foot Flowers, all accompanied by a Velvet Underground soundtrack piped through the exhibition halls. (Warhol managed the band and they were supposed to play at the opening of the 1968 exhibition, but it proved beyond the museum’s financial means to fly them over.)

At the time of the original show, Sweden was firmly in the grip of the debates sweeping the western world–feminism, pacifism and anti-capitalism. This was the year of the Vietnam War, student riots, the assassination of Martin Luther King Jr. and the Soviet invasion of Czechoslovakia. In left-leaning Sweden, Warhol’s shiny celebration of consumerism was controversial. “Warhol has filled me with distaste,” the critic Ulf Linde wrote in the broadsheet Dagens Nyheter.

Others saw Warhol’s work as a critique of capitalism. In the newspaper Aftonbladet, the Marxist critic Bengt Olvang described the artist as “an intense, disillusioned truth-seeker.” This is an aspect that John Peter Nilsson, the curator of the current exhibition at the Moderna Museet, is keen to draw out. “He is not the cynical entrepreneur that many have made him out to be,” Nilsson says. “He showed the underside of the American dream.”

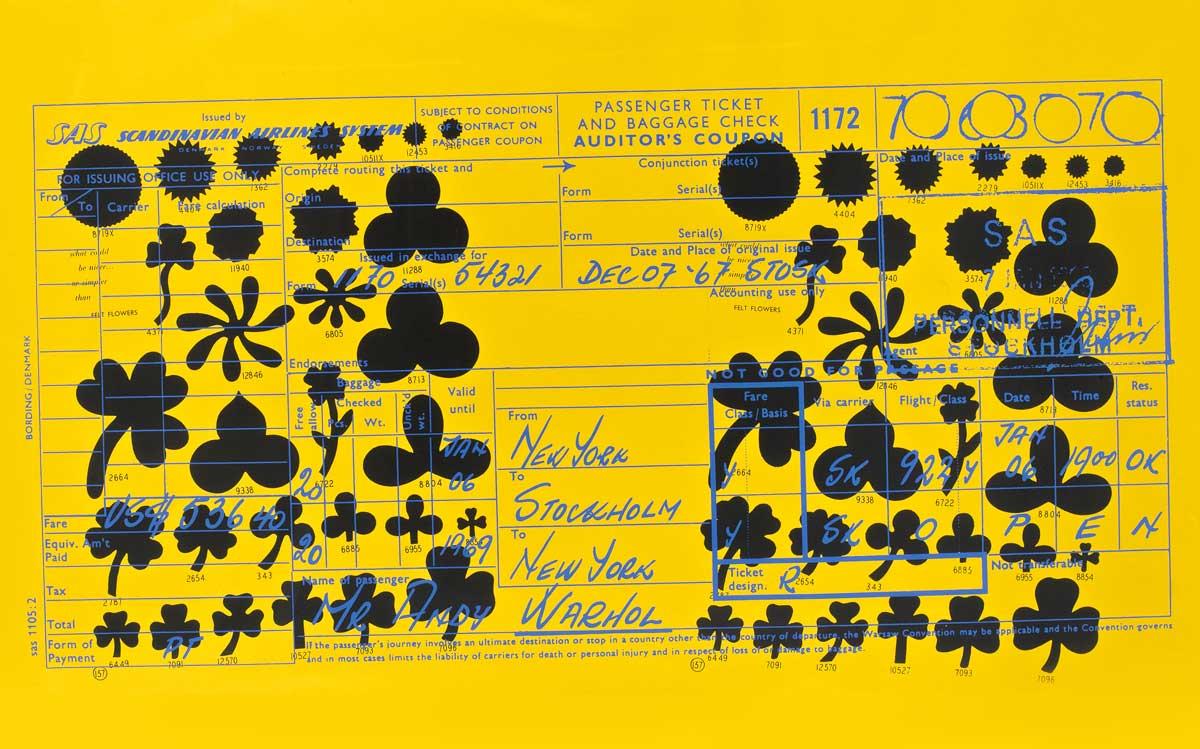

The 1968 show was a public success, with more than 23,000 visitors. The 640-page catalogue attracted international interest. It featured Warhol’s best-known quote–a sentence he almost definitely never uttered. Olle Granath, an art critic who worked on the catalogue, remembers Pontus Hulten, the Moderna Museet’s director at the time, asking him for a pithy Warhol quote. Hulten suggested: “In the future, everybody will be world-famous for fifteen minutes.” Granath said he hadn’t seen the quote in his Warhol material. Hulten paused. “If he didn’t actually say it, he very well could have, so we’ll put that in,” he replied.