The mind-boggling, semi-new scientific field of neuroaesthetics may turn the art world on its head––in a good way. Emerging brain research proves what artists and art lovers have sensed all along: Art can make us feel better. But that’s only the beginning. There’s more, much more, to neuroesthetics.

“Neuroaesthetics emerged in the late 1990s, and nobody is clear on who coined the term, but a simple definition is that neuroesthetics is the study of how arts measurably changes the body, brain, and behavior and how this knowledge is translated into practice,” said Susan Magsamen, founder, and director of the International Arts + Mind Lab Center for Applied Neuroaesthetics at Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine.

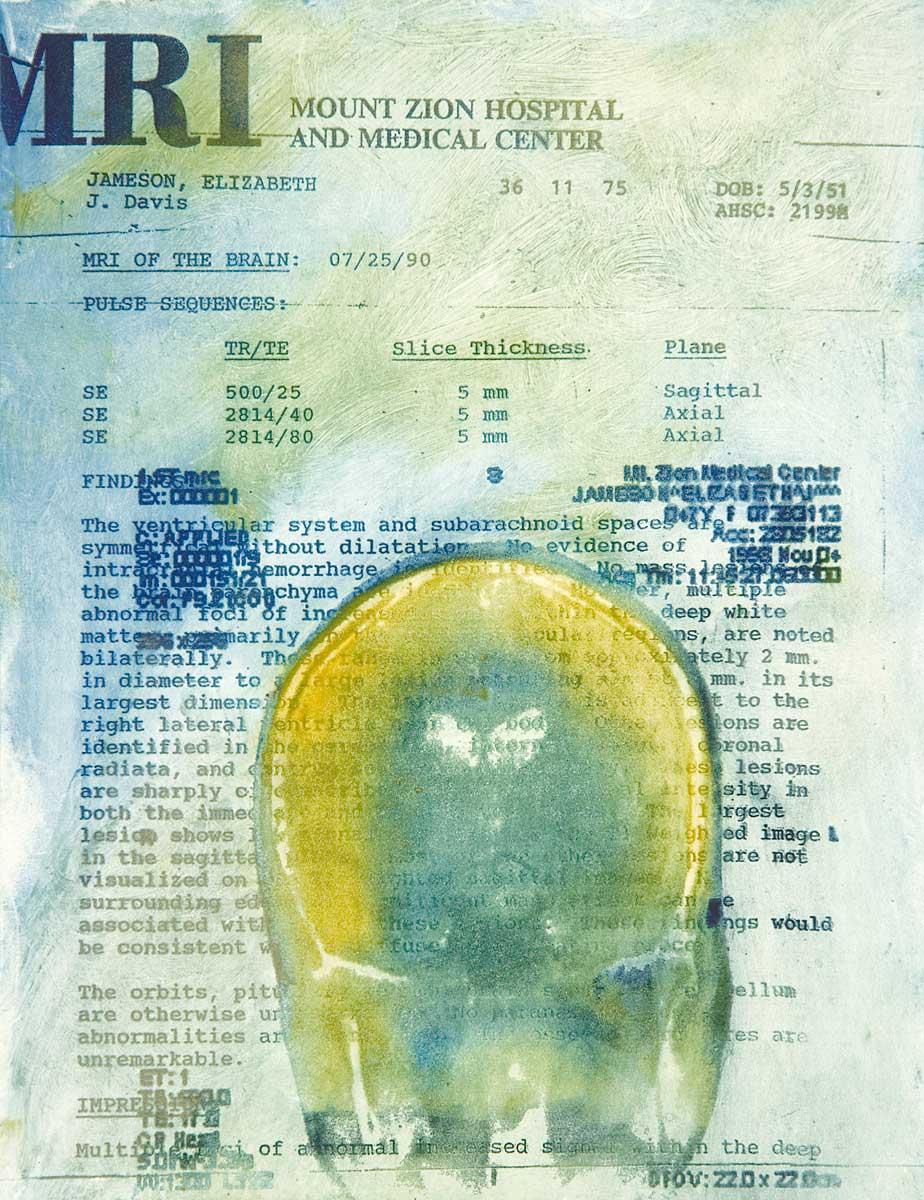

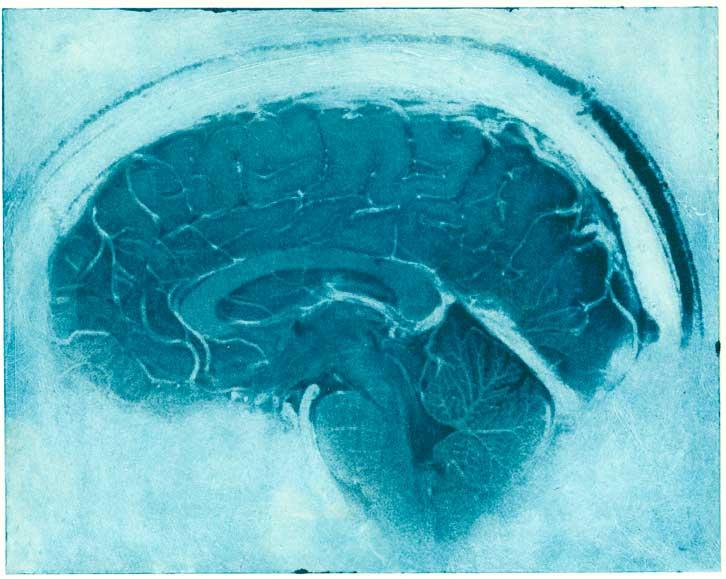

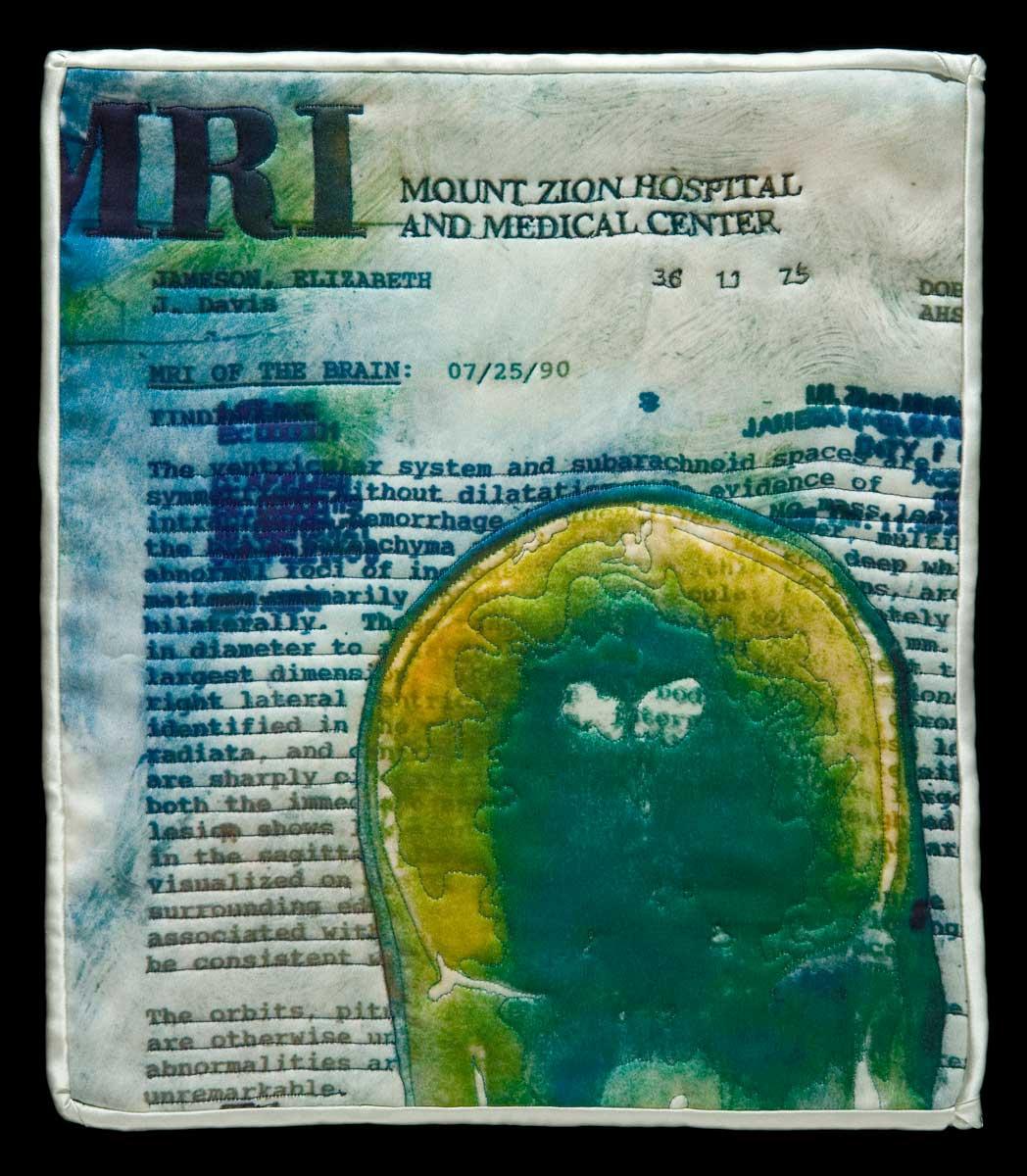

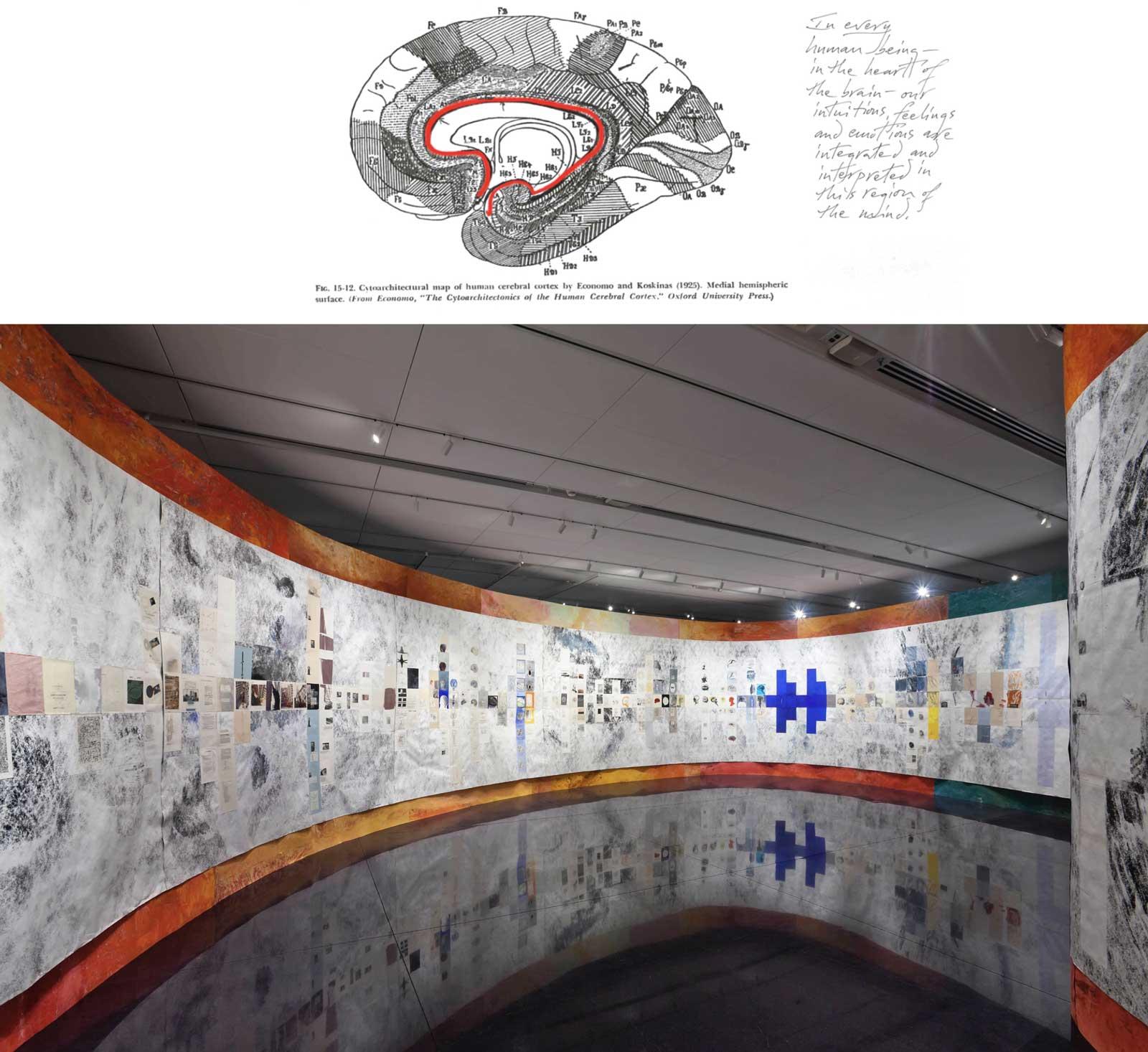

Neurology received a boost from an array of brain-imagining technology, allowing scientists to observe and document the effects of visual art, along with music and dance, upon the human brain. And while the amygdala, hippocampus, and other brain components are almost infinitely complex, the basic neuroaesthetic findings are straightforward.