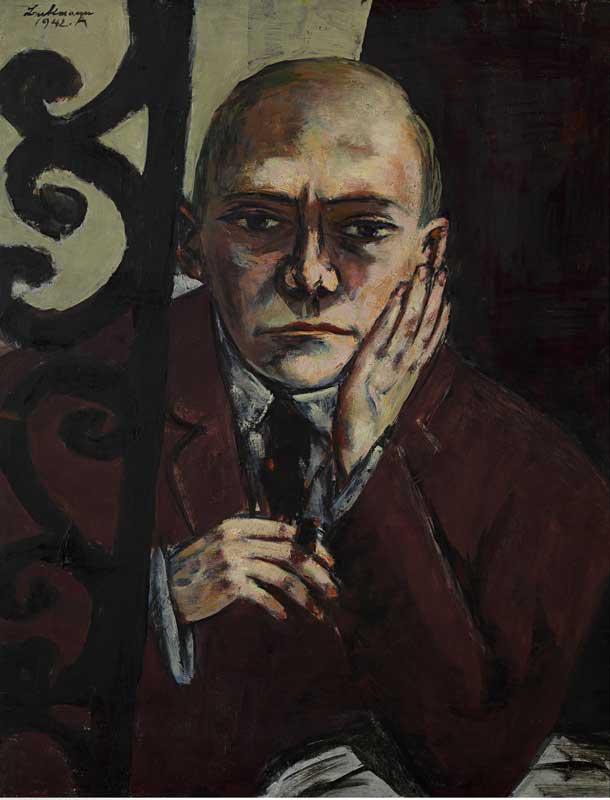

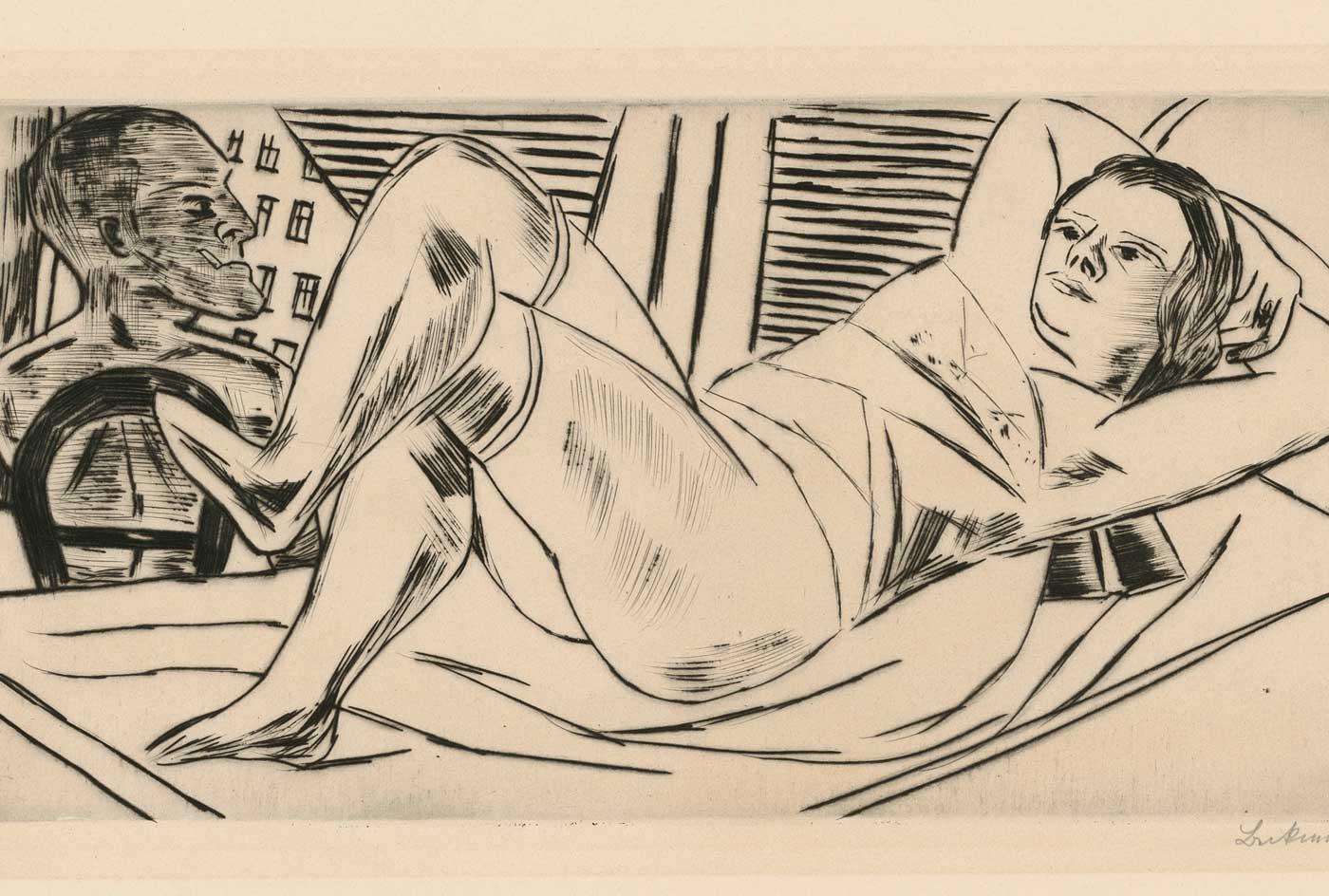

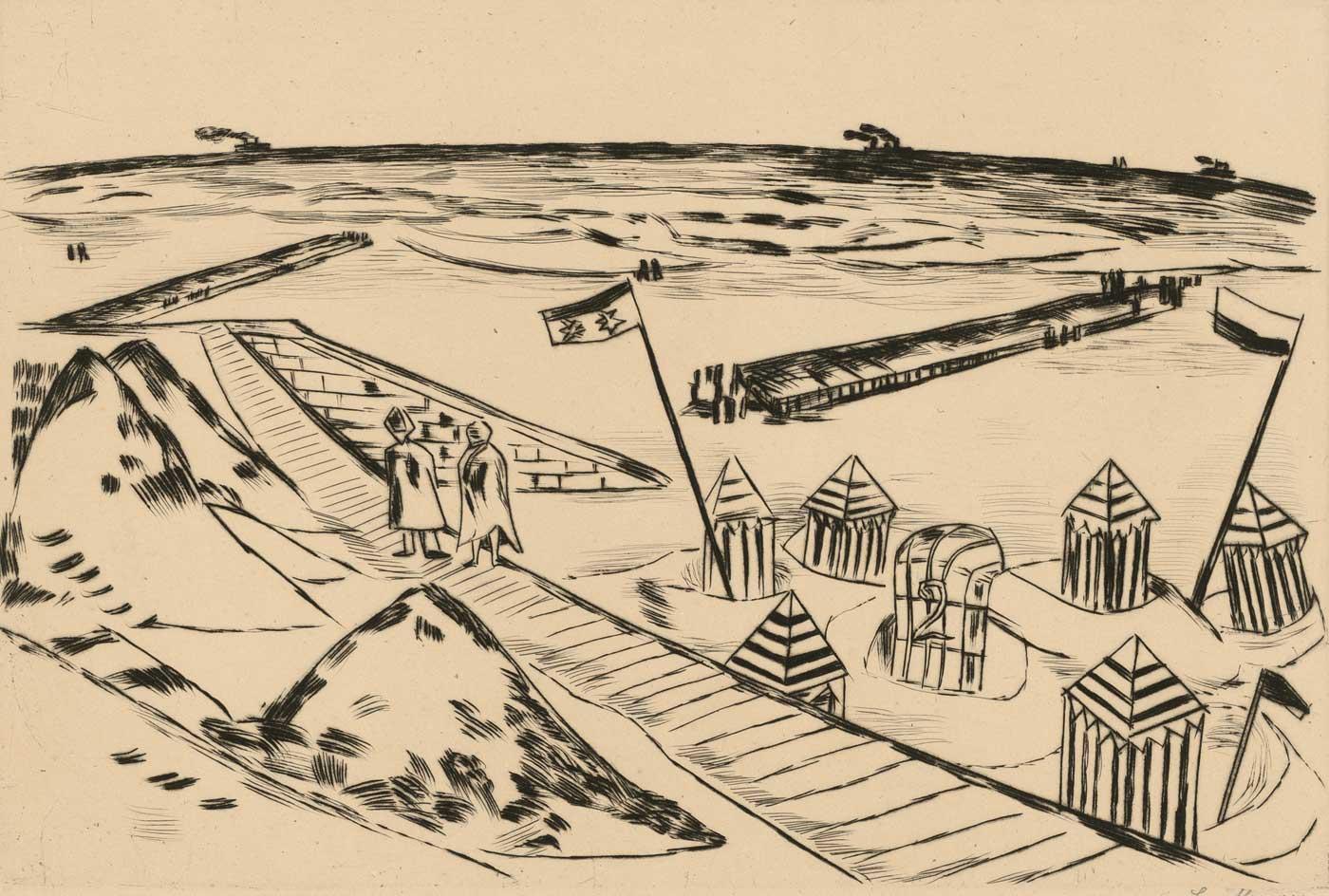

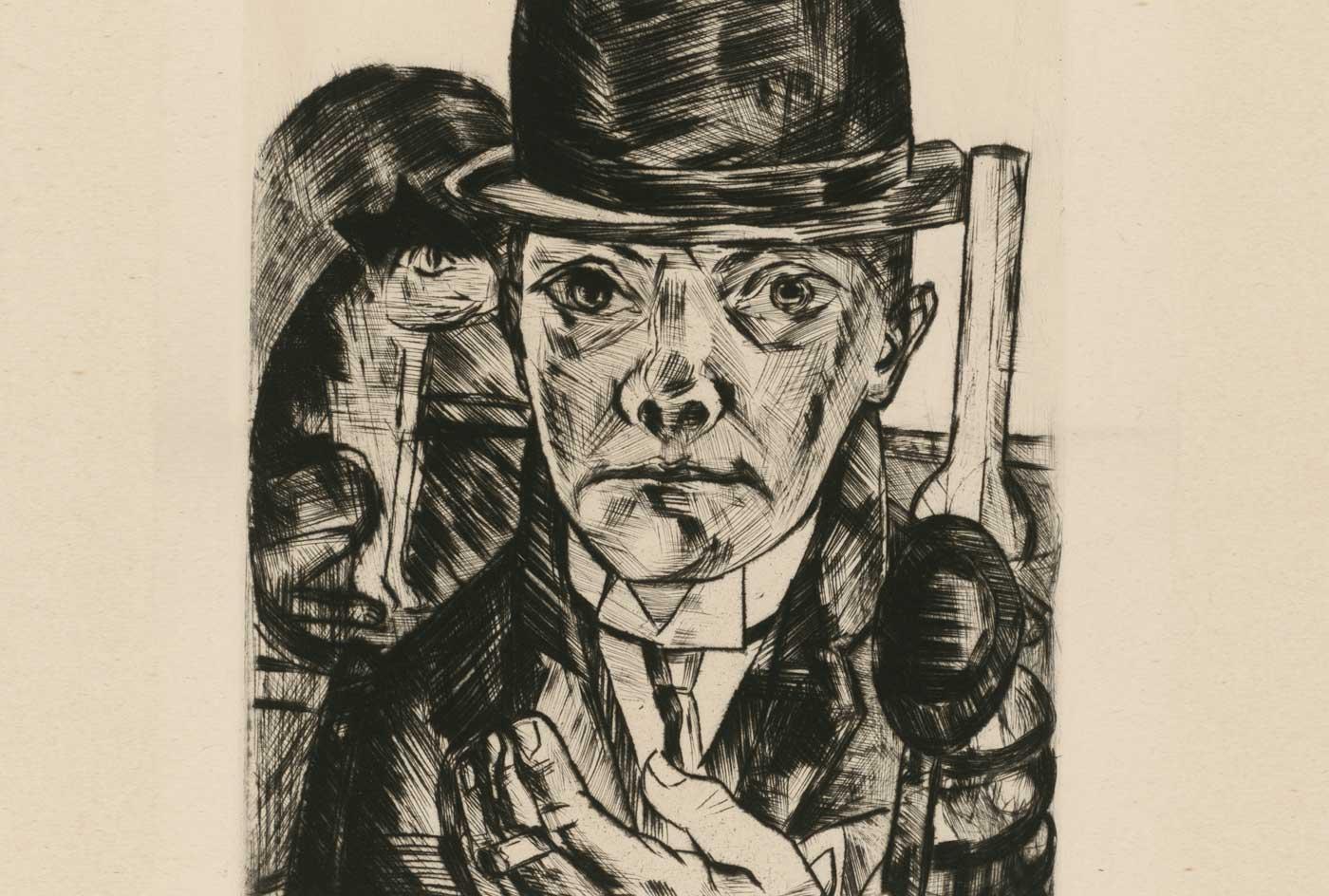

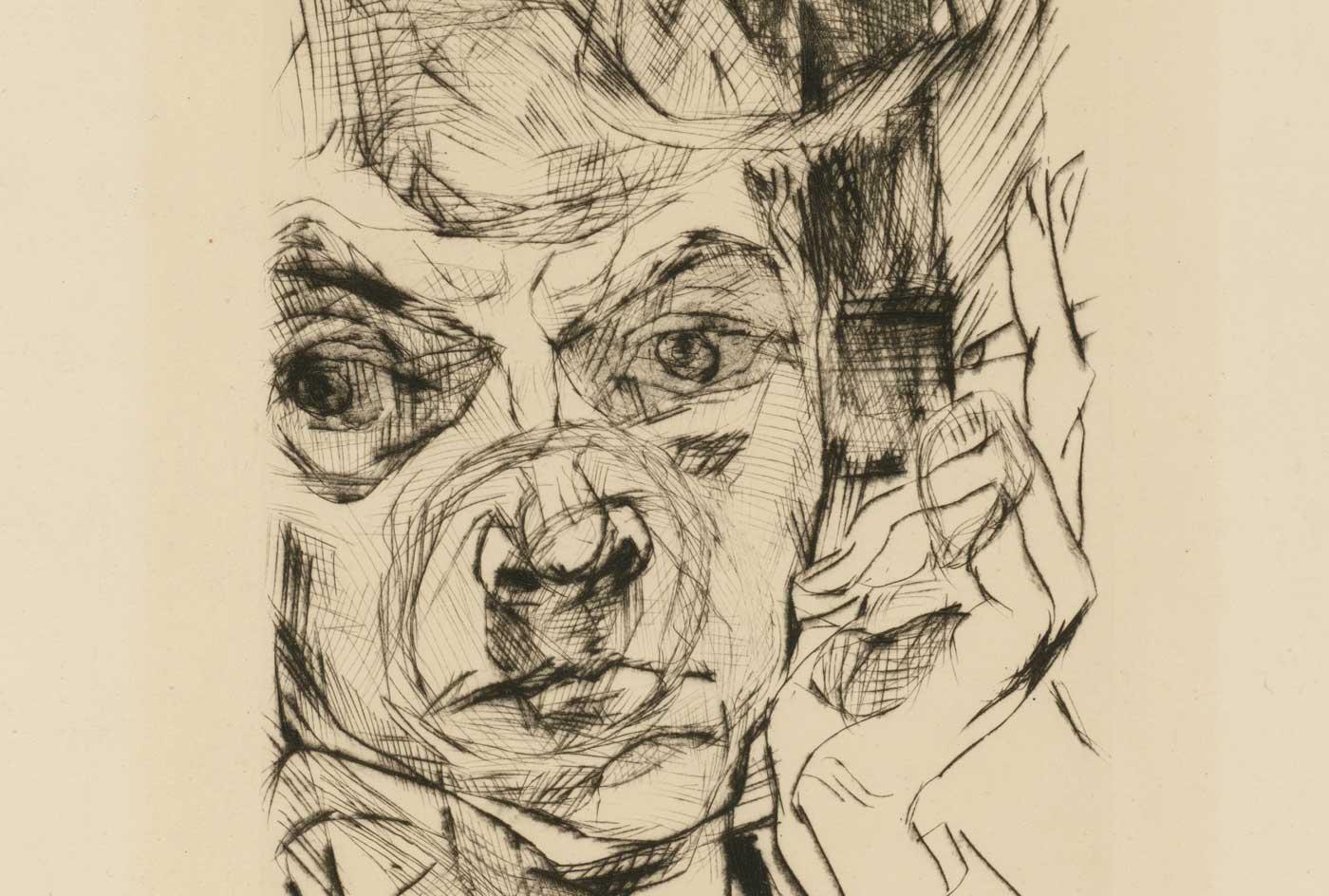

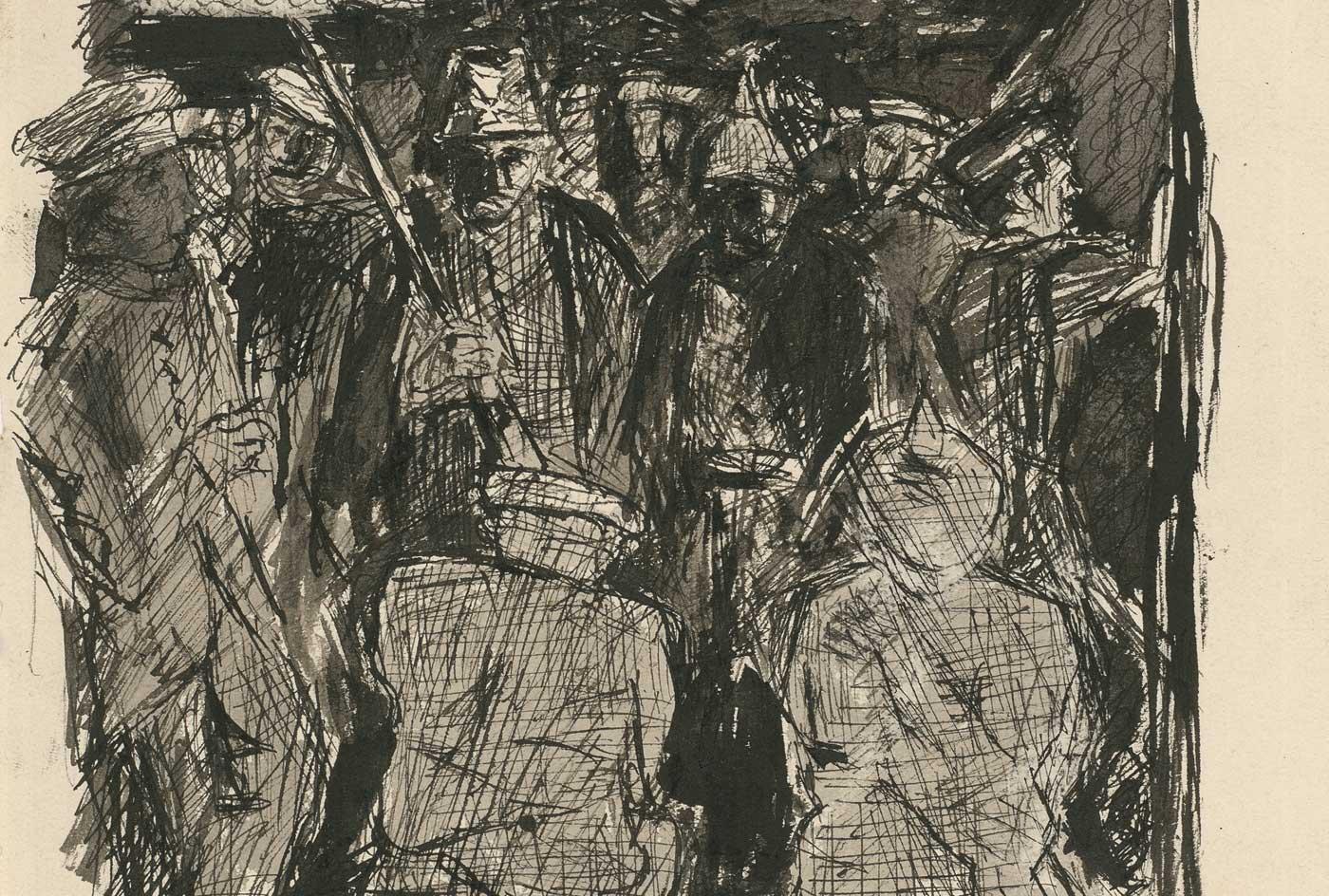

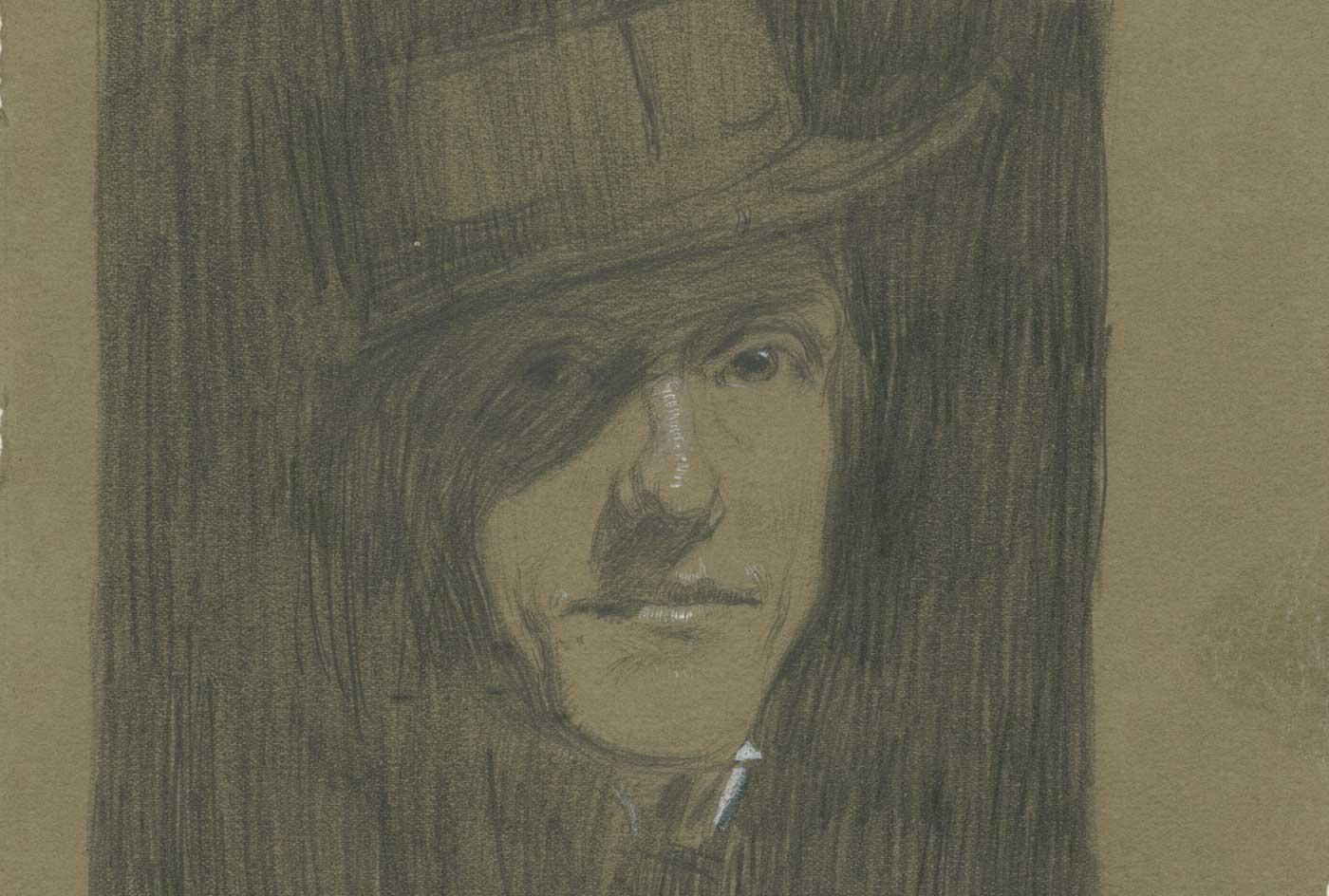

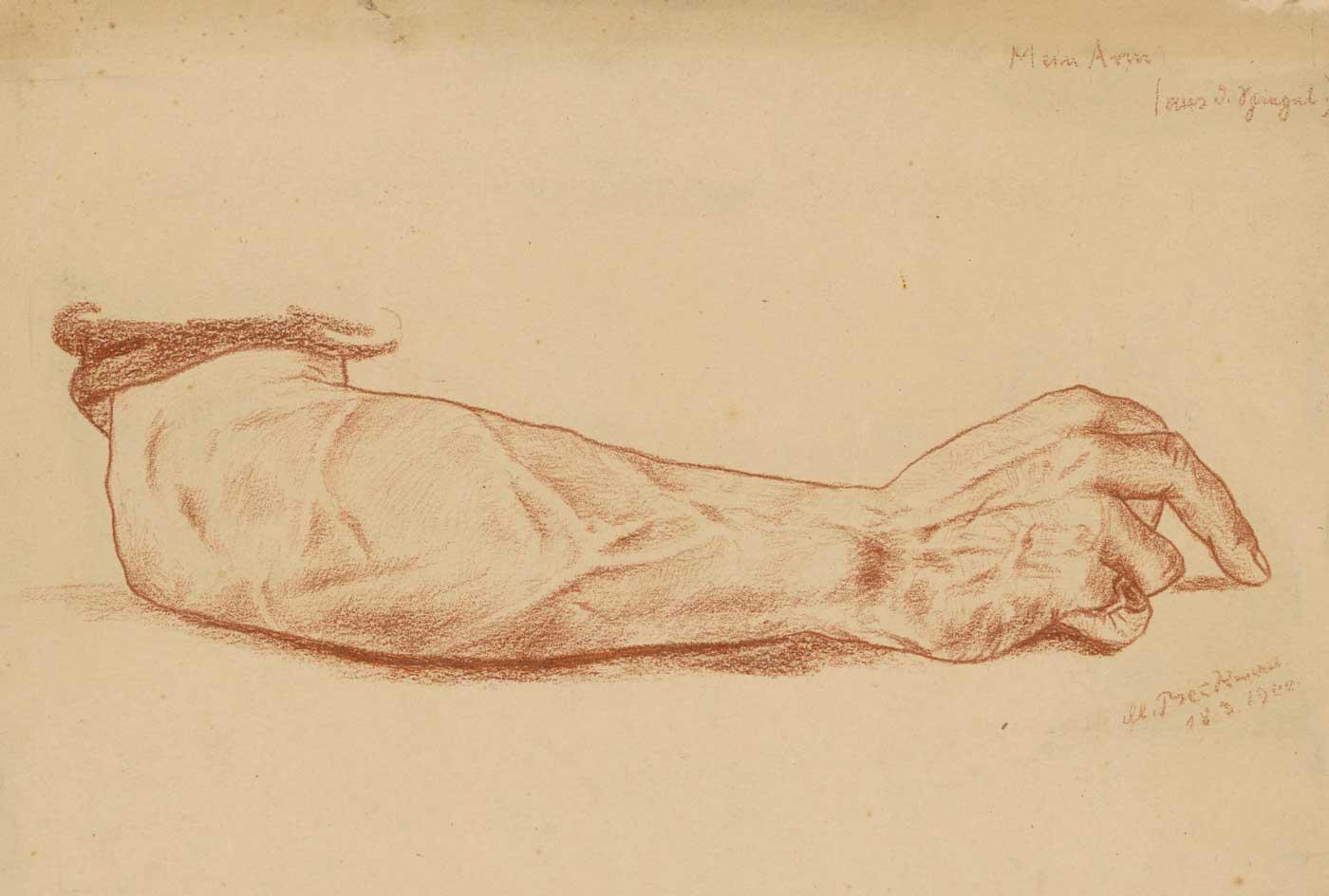

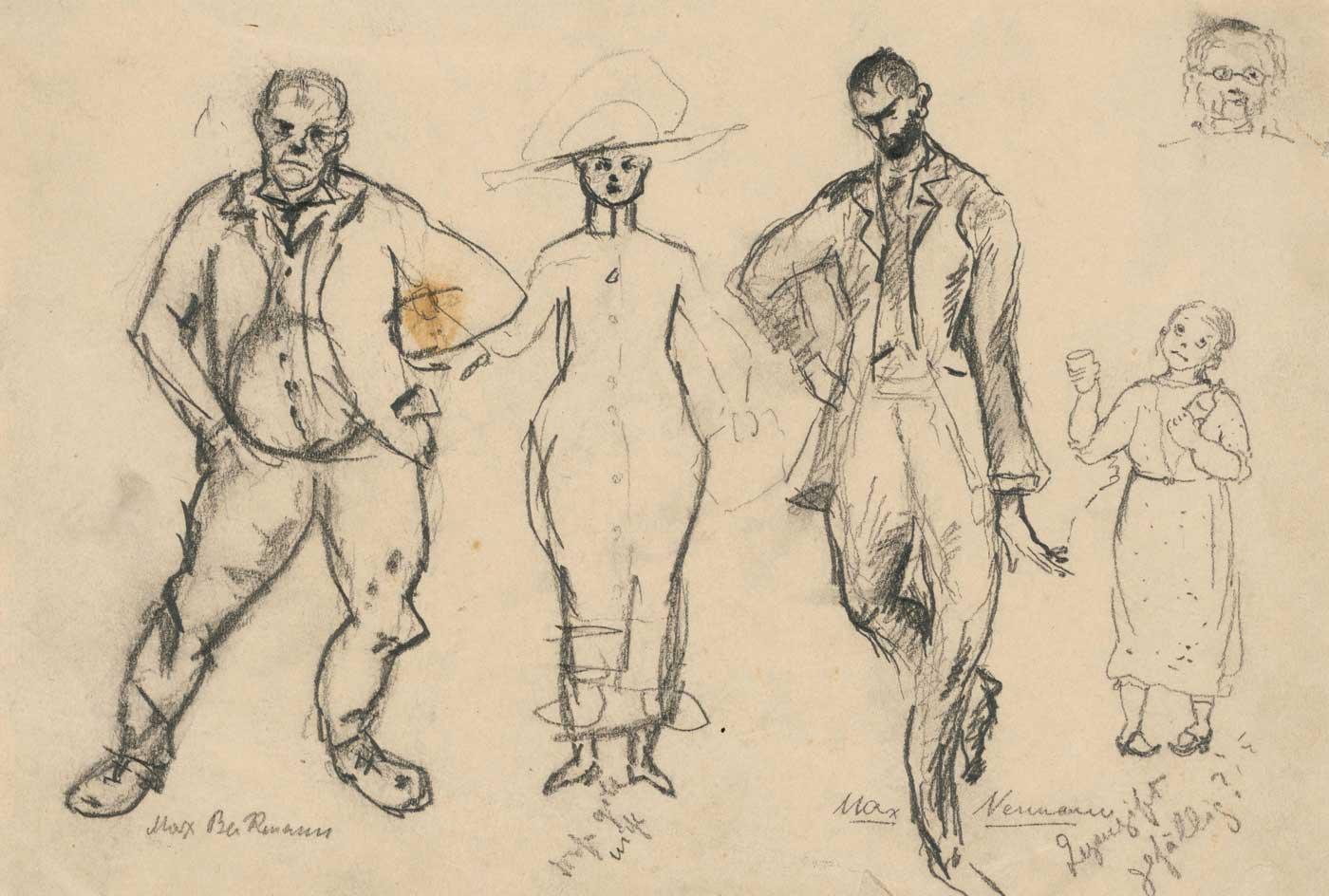

When Berlin’s state museums inherited an important collection of works by Max Beckmann in 2017, they were delighted at this unforeseen stroke of good fortune. At the same time, museum officials were aware that the bequest carried what they termed a “moral and ethical responsibility.”

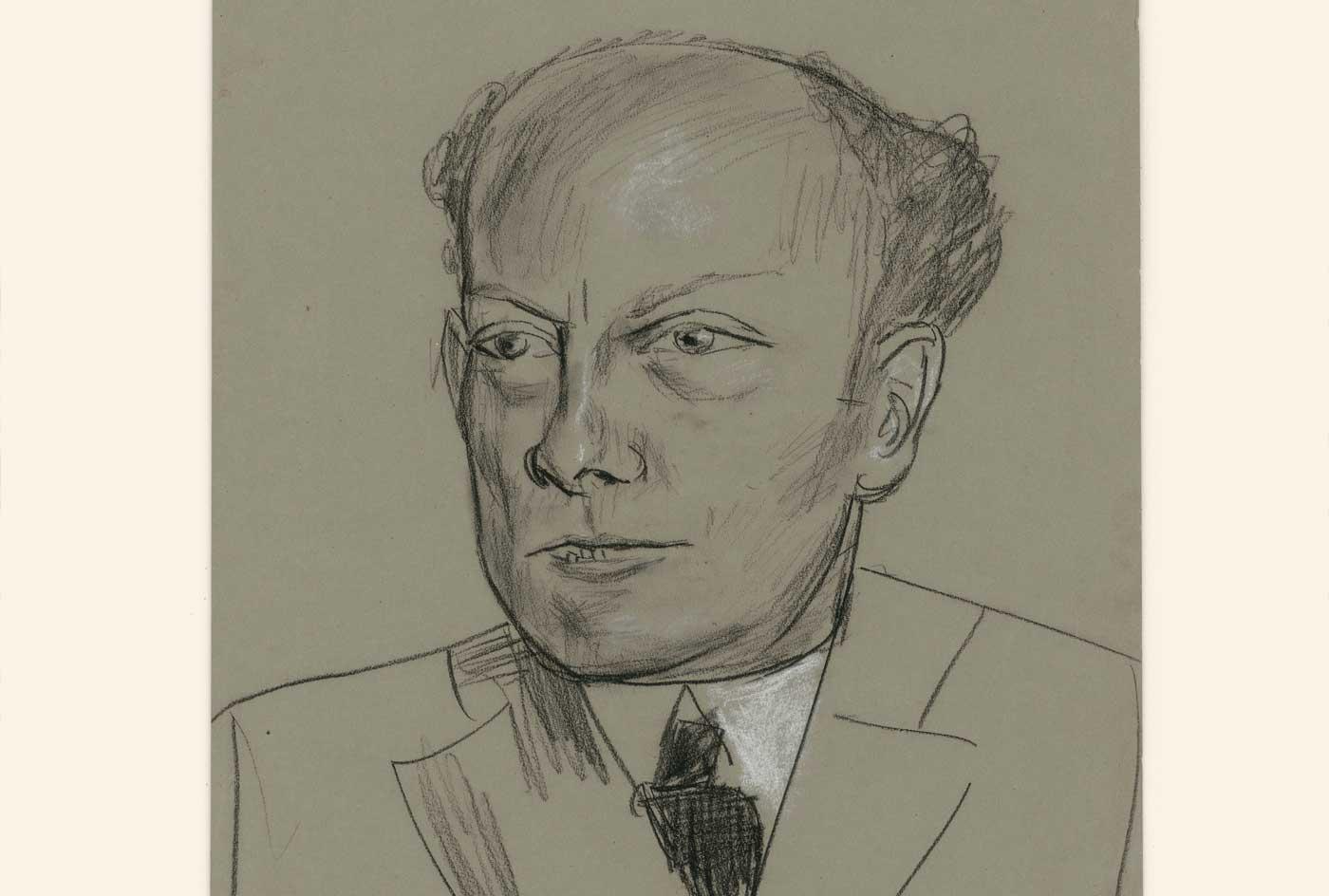

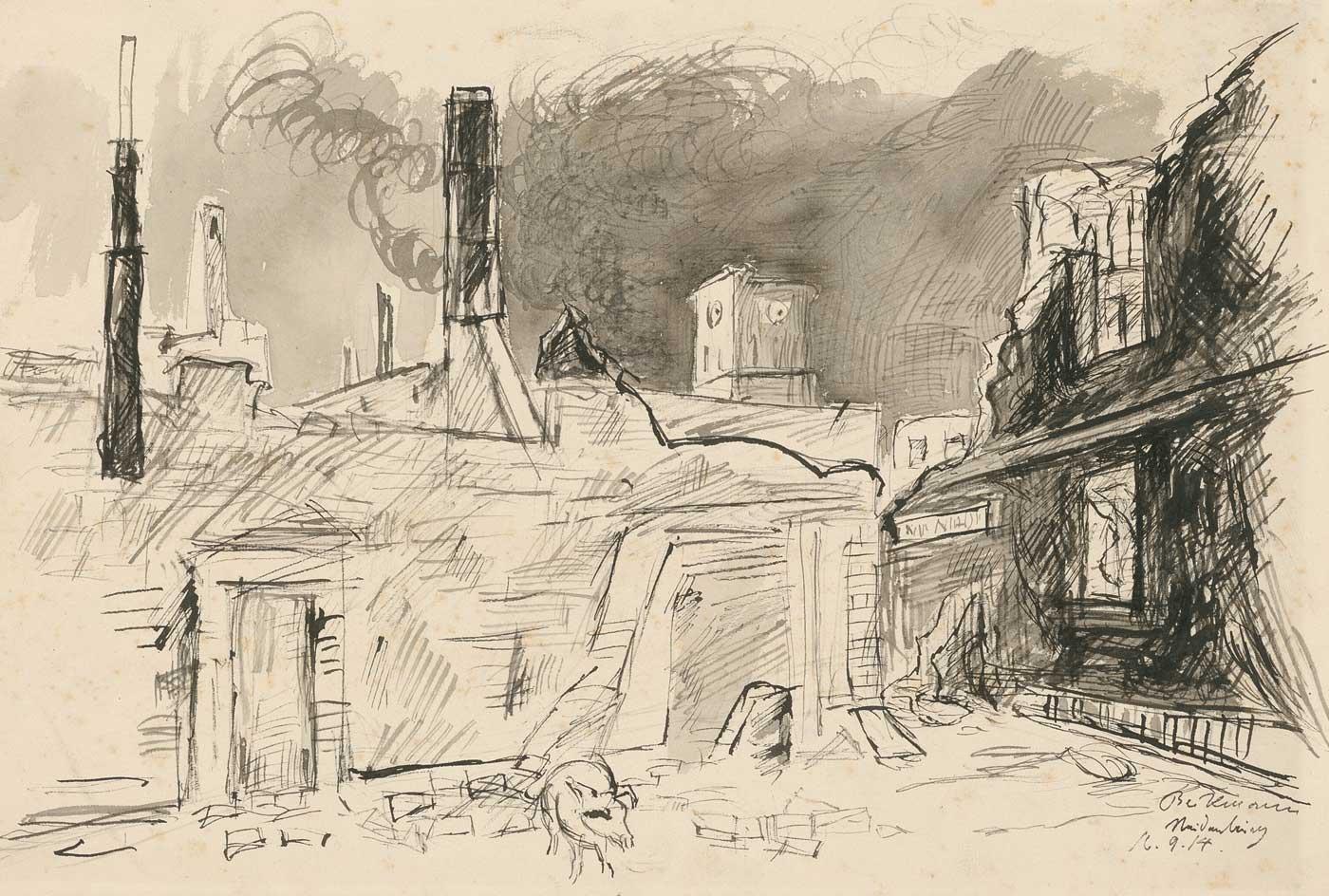

The unexpected windfall, comprising forty-six drawings, fifty-two prints, and two paintings by Beckmann, came from Barbara Göpel, who died last year at the age of 95. Like her husband, she was an art historian specializing in Beckmann. Erhard Göpel, however, also served as a key member of the Linz Special Commission, the team of dealers who purchased–and looted–art across Europe for the “Führermuseum” that Adolf Hitler planned for his hometown of Linz but never built.

Göpel played an important role in looting Jewish art collections in Nazi-occupied France. As the art historians Christian Fuhrmeister and Susanne Kienlechner wrote in a 2012 portrait, “he was neither a cold ideologist, nor a soulless businessman, but he was ambitious, adaptable and opportunistic enough to put his skills at the service of a criminal system.”