The two artists first met in 1962 through the Guinness family, Hockney later acknowledging that “Lucian was very famous even at the time I was still a student." By the time Freud sat down to paint his friend in 2002 he was almost eighty years old and Hockney was aged sixty-five. Freud was considered Britain’s greatest living painter, while Hockney was among the most influential British artists of the twentieth century (recently the subject of major retrospective exhibitions in Europe and the US). Just over a decade earlier, in 1990, he had turned down a knighthood, on the grounds that he didn’t ‘care for a fuss.’

Every day of those four months in 2002, Hockney would walk through Holland Park to Freud’s flat: “sometimes I was early, and he would leap up the stairs two at a time. No slouch at eighty. He never wanted to be seen as inactive." Arriving around 8:30 am each morning, the sittings started with a cup of tea brewed by Freud on a grease-covered stove. “I liked the old-fashioned bohemia of it all. The plates with old beans on them from the last night, or even last week, it was like student days, very appealing, very appealing after all those very clean New York lofts. I told him you can’t have a smoke-free bohemia by definition. He let me smoke–‘Don’t tell Kate Moss’ was his request."

The sittings provided a meeting of minds that spanned decades of shared admiration, and for Hockney it was an illuminating experience. He found Freud’s technique fascinating, the older artist’s refusal to pre-mix colors to speed up the process a deliberate ploy to afford him as much time with his sitter as possible. As a result, conversation between the two artists flowed freely: “Lucian’s talk was always fascinating. Sometimes it was just gossip about people we both knew, very amusing, very good put-downs that made me laugh. But we talked about drawing a lot. Rembrandt, Picasso, Ingres, Tiepolo... We talked a lot about Rembrandt drawings and how everything he did is a portrait, no hand or face is generic."

Bella Freud, daughter of Lucian Freud, recalled: “When David Hockney was sitting for this painting it was exciting to see them together, like the two cool older boys at school who were engrossed in each other’s conversation. I liked hearing Hockney say that he enjoyed the slowness of the painting’s progress, so he and Lucian could chat. We all loved chatting with dad, he was so interesting about everything.”

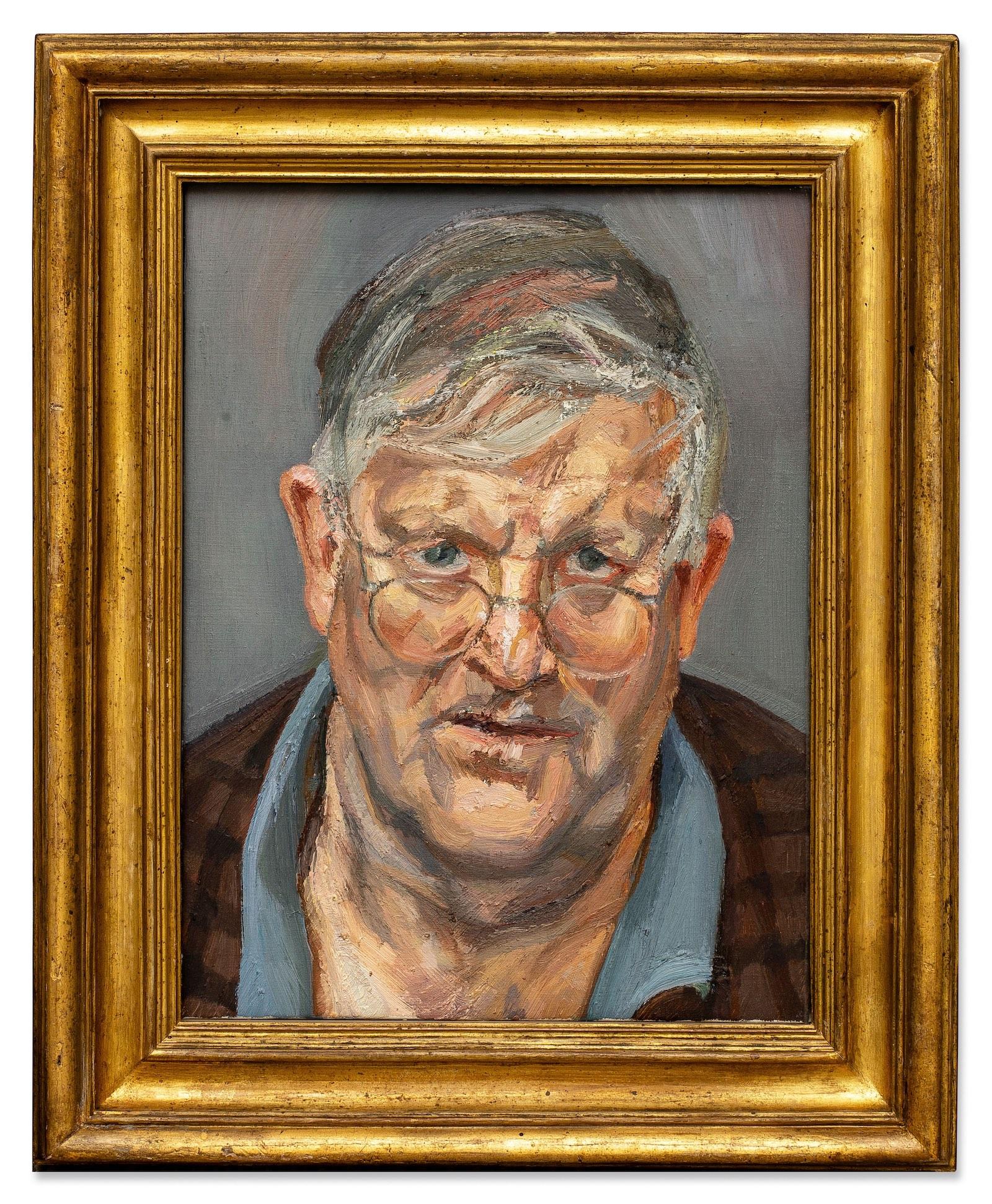

Hockney’s portrait was the latest in a series of illustrious sitters and subjects painted the year prior, from Queen Elizabeth II to Kate Moss. The portrait shows Hockney’s face close up, mid-thought, revealing his warmth and inquisitiveness as he peers over his round spectacles. Freud’s fascination with portraiture was restricted mainly to those closest to him. Whether self-portraits, or portraits of friends, lovers, criminals, members of the aristocracy, and notably, other artists, Freud only painted the significant protagonists in his everyday life. And, within the entirety of his output, only a small percentage of works were given titles identifying their subject by name. It is of no small significance that Freud’s portrait of Hockney names its sitter with such deliberate emphasis.

One of the sittings was brilliantly captured on camera by David Dawson, Freud’s former assistant. In one image (illustrated on page 1), Hockney wears an expression almost identical to the one caught in Freud’s painting, whilst Freud, mid-stride, enters the studio, brushes in hand. In this instance, Dawson anticipated Freud’s apparent surprise on re-entering the studio to find a camera pointed at him while Hockney was waiting, ashtray at his feet, matching the talkative expression of his portrait. Dawson recalled: “I never kept a diary and didn't want to… But because I was so fascinated with what was going on in the studio I would have a little camera and take a picture or two. It started really when I was taking a picture of David Hockney in the studio, who had been sitting for Lucian, and Lucian walked in.”

Though Freud and Hockney might appear to be fundamentally different when considering the body of work they each produced – Freud confining himself day-in day-out to painting within the four walls of his studio; while Hockney constantly changed and challenged his methods and mediums, from more traditional practices of drawing and painting through to photography, video and his current digital work on iPads – at the heart of both their practices is the unwavering fascination with finding ways to paint exactly what they see; observation, perception and the process of creation are the very foundations of their art. Throughout his career, Freud lived and translated his physical circumstances, experiences, and relationships into compositions that communicate the universal truths of human psychology and emotion. Hockney himself concluded: “It’s a duration, not a moment; not many people could look at a face for 120 hours and constantly do something with it."