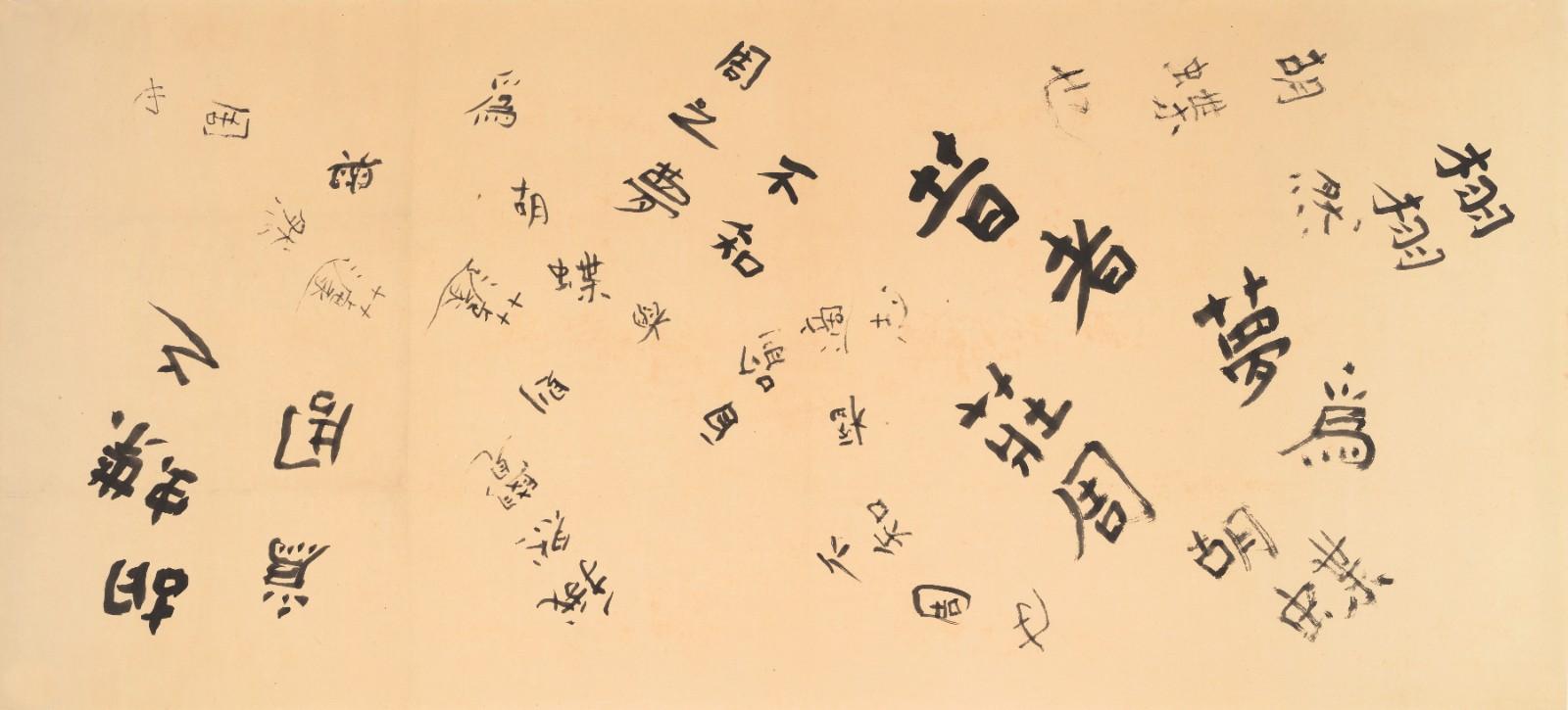

The friendship between the two artists did not only enrich their private lives, but also the development of their art in the post-WWII decades. “They were both concerned with the beauty of tradition and the power of abstraction,” said Dr. Karin G. Oen, one of the curators of the exhibition Changing and Unchanging Things: Noguchi and Hasegawa in Postwar Japan, currently on view at the Asian Art Museum in San Francisco. Their friendship and artistic collaboration was based on the fact that they were both “interested in synthesizing modern art and modern forms with traditional Japanese aesthetics and materials,” noted Dr. Oen.

Isamu Noguchi was born in 1904 in Los Angeles, the son of the Japanese poet Yonejiro Noguchi and American writer Léonie Gilmour. He was a landscape architect, sculptor, and designer (the iconic Noguchi Table is one of his creations). Saburo Hasegawa was born in Japan in 1906, graduated from the Tokyo University of Arts in 1926, studied painting in Paris in the 1930s, and exhibited his works in Europe and the US. During Noguchi’s trip to Japan in 1950, they traveled together around the country visiting temples and cultural sites. For both artists, it was important to explore art and its social value as well as the impact that WWII had in the creation of the new world order. The birth of globalization led Noguchi and Isegawa to wonder about their own cultural identities and the importance of artistic roots in an ever-changing and more globalized world.

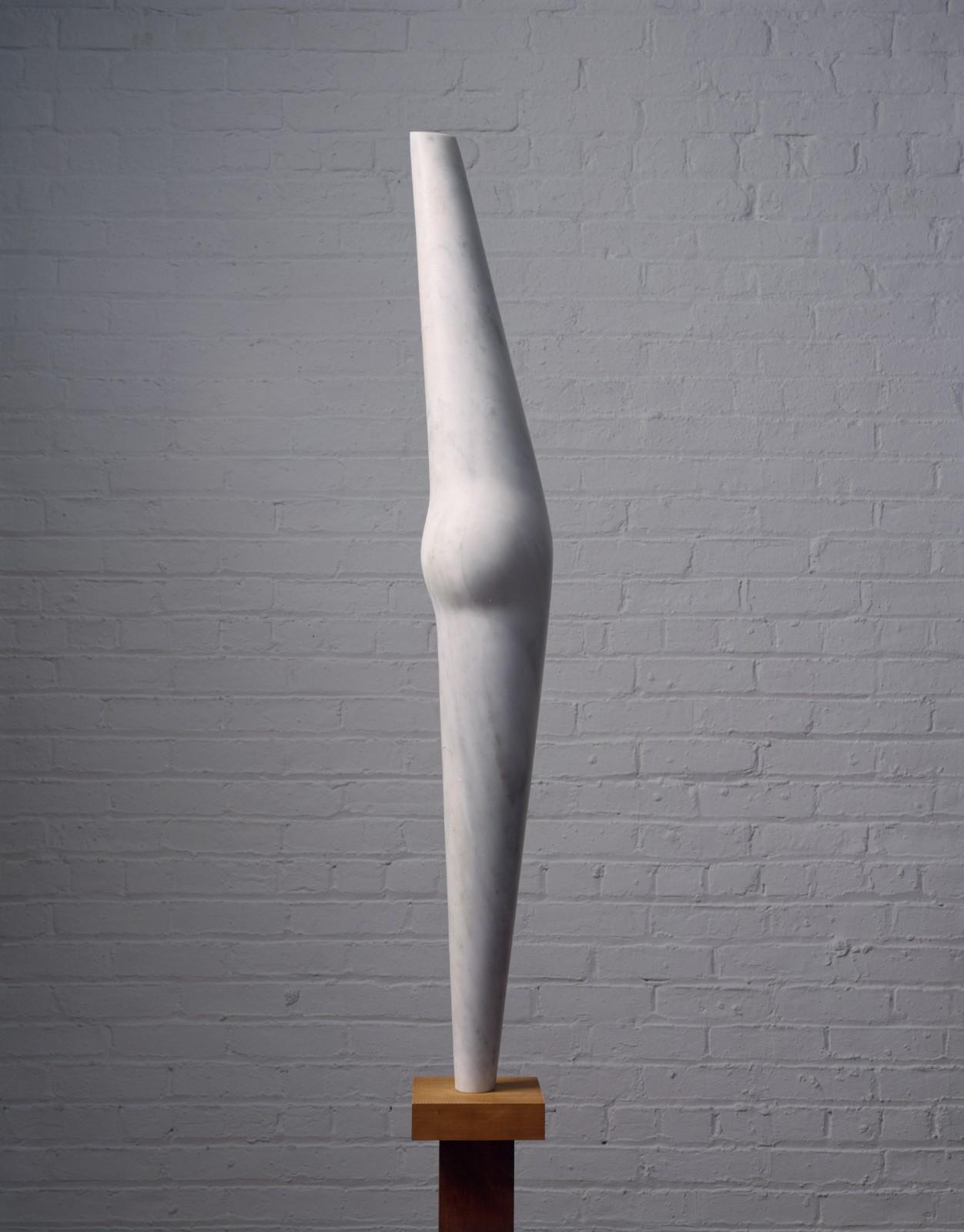

The strength of Noguchi and Hasegawa’s works, and of this exhibition, is simplicity. The essential, visible to the eye, emerges from Noguchi’s sculptures and Hasegawa’s calligraphies and drawings. This simplicity gives space to meaning and abstraction. For instance, Noguchi’s jars Man and Woman (1952) were created according to traditional Japanese craftmanship using Bizen stoneware clay and made by ceramists of the Kaneshige Toyo studio. These jars represent two abstract human forms while maintaining their practical purpose as vessels.