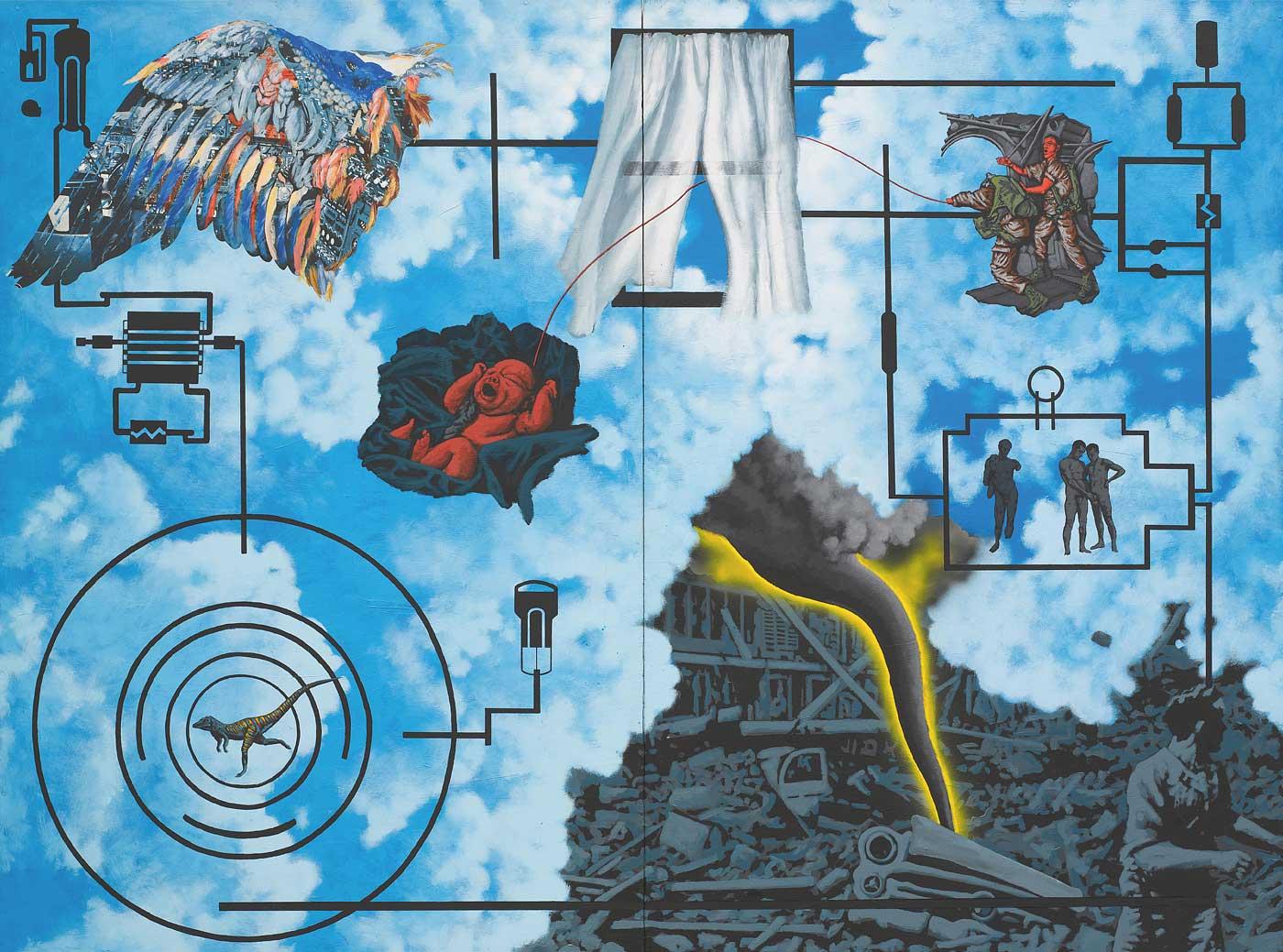

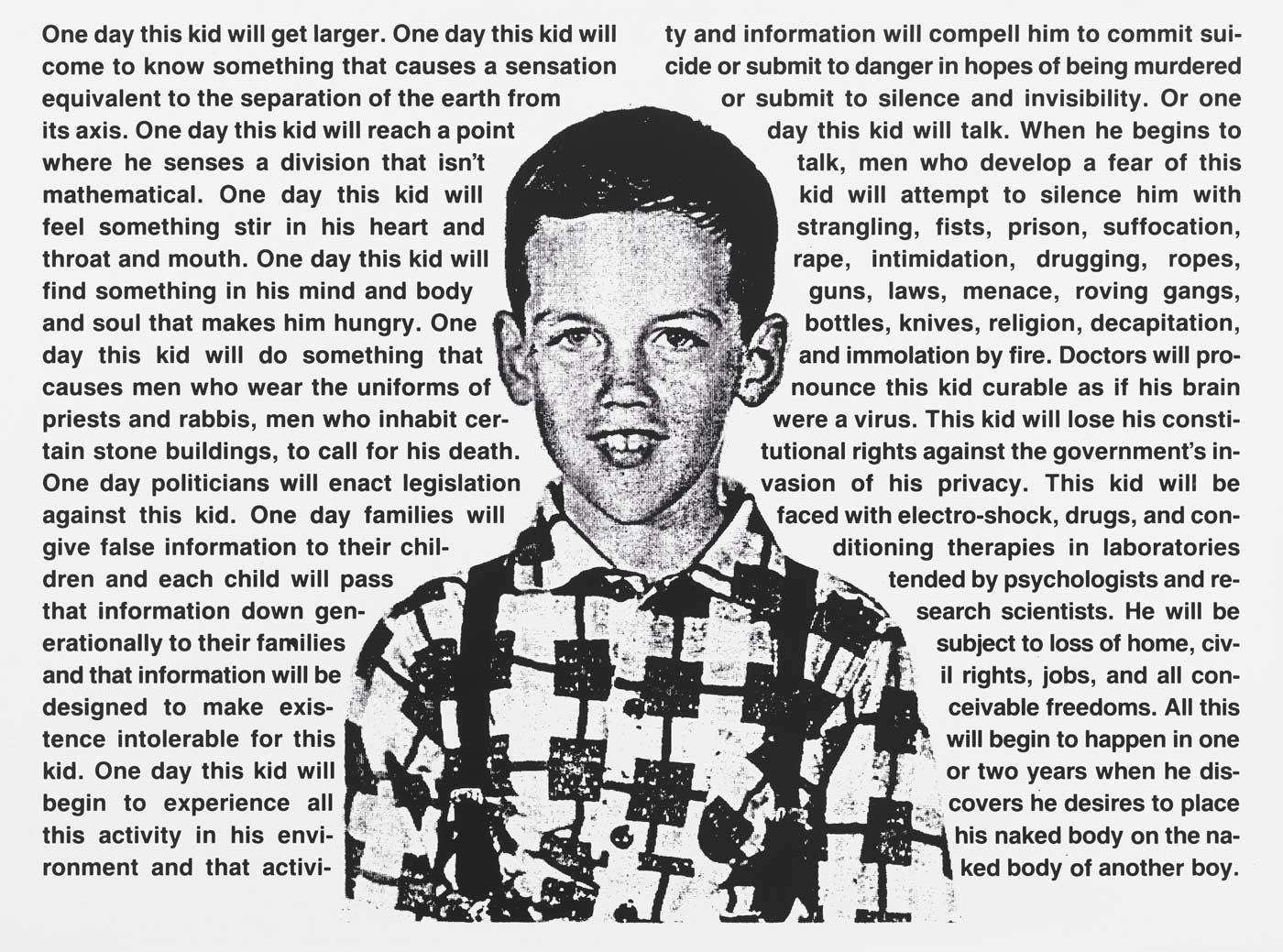

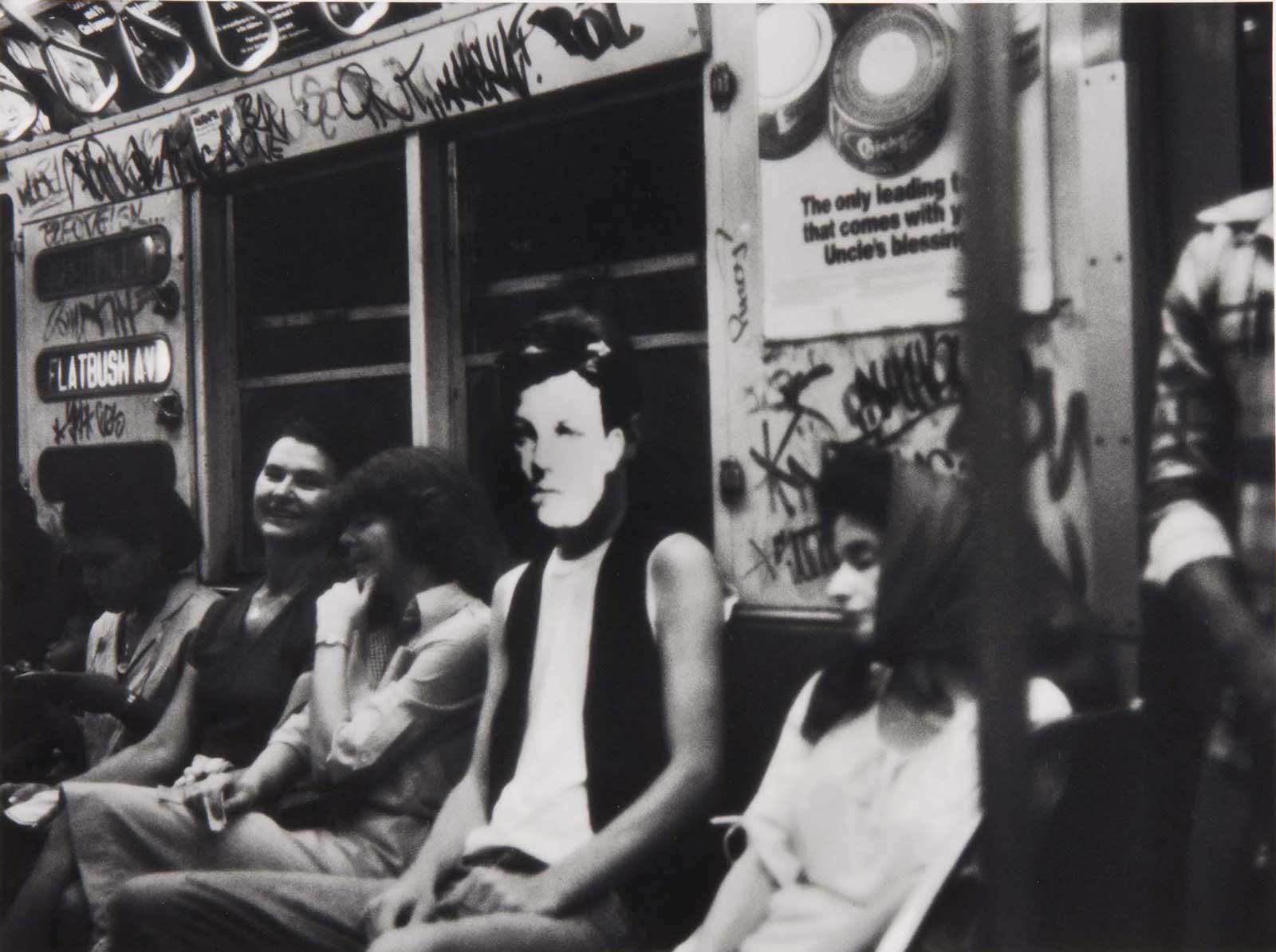

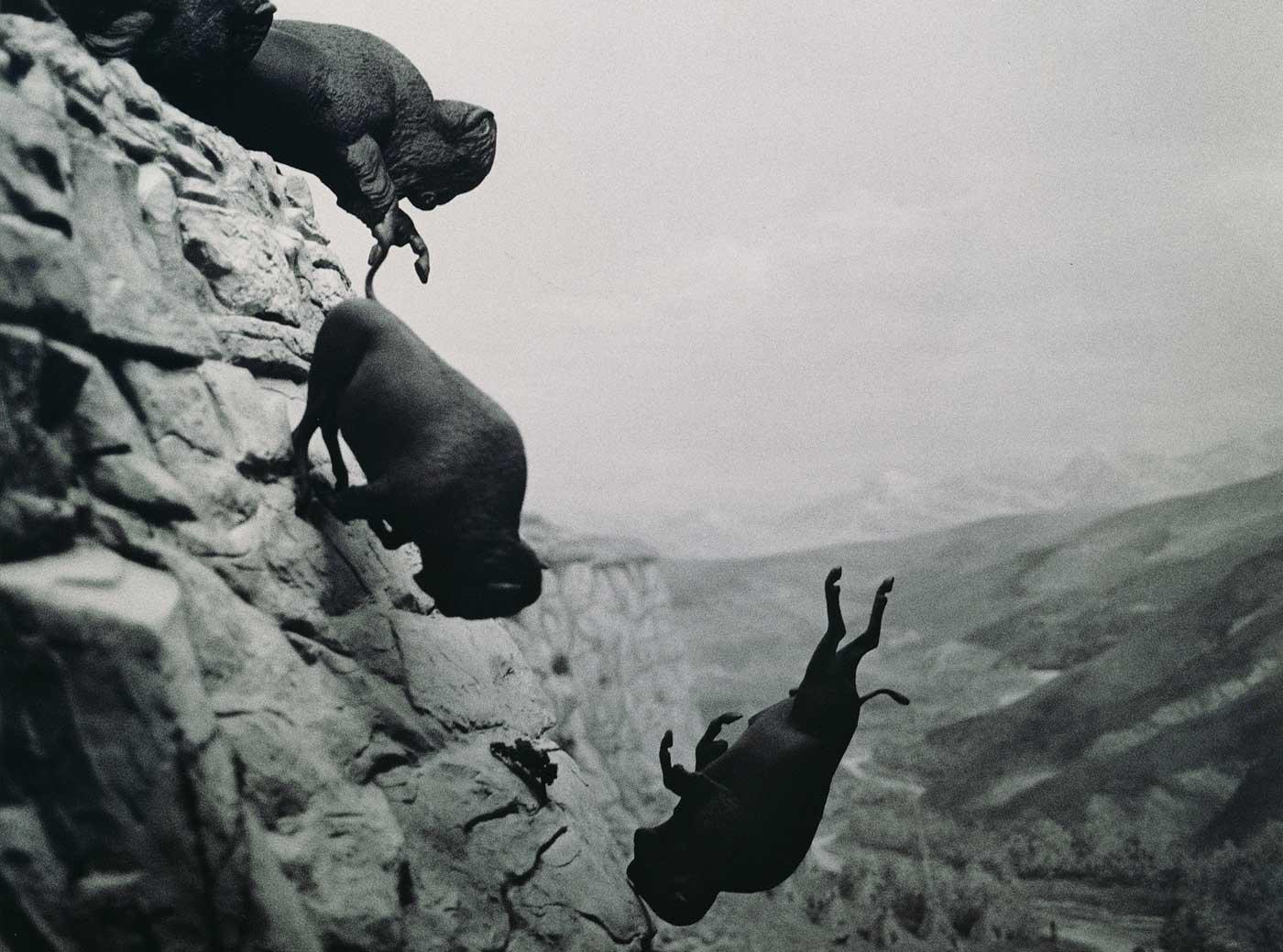

On July 13 the Whitney Museum of American Art opened David Wojnarowicz: History Keeps Me Awake at Night, an expansive retrospective of the prolific artist’s life and career. Adroit across a variety of media including photography, painting, collage, poetry, prose and music, Wojnarowicz is a key figure in two of today’s most important art historical contexts: queer art and the emerging historicization of the 1990s. Wojnarowicz and his practice connect to the defining socio-cultural events of the decade, including queer and AIDS activism, New York City’s essential downtown art scene, and the culture wars. A central figure in the National Endowment for the Arts (NEA) controversies that symbolized the ideological battles against neoconservatism in the last decade of the 21st century, Wojnarowicz sued the agency for censorship after they withdrew support from his exhibitions.

At times, Wojnarowicz’s connections to these contexts have threatened to overwhelm his work itself, particularly his role with the NEA. The exhibition at the Whitney, however, gives Wojnarowicz’s prolific artistic practice its due, weaving in contexts and histories, but always leading with the work itself. One of the primary themes of the Whitney exhibition is the artist’s connections, and disconnections, to the social world. His collaborators, his influences, the scenes he traveled in, as much as his preoccupations with alienation and manipulations of power, permeate the exhibition’s approach. This is fitting as Wojnarowicz’s oeuvre teems with allusions to his outsider status, family tragedy, and a search for an artistic language expressing the lives and terms of outcasts and cultural and environmental refugees, as well as references to icons, idols, peers, and lovers who shaped his life and work.