Just in time for Halloween, the Morgan Library and Museum presents an exhibition to get bibliophiles, art, and movie lovers in the spirit of things. It’s Alive! Frankenstein at 200 explores the history of Mary Shelley's horror masterpiece and its continued cultural influence, examining its origins and its massive impact. Her story and its characters have come off of the page not only in innumerable tv and movie versions, but have become a metaphor, one that is seemingly universal and applicable across cultures and throughout two centuries.

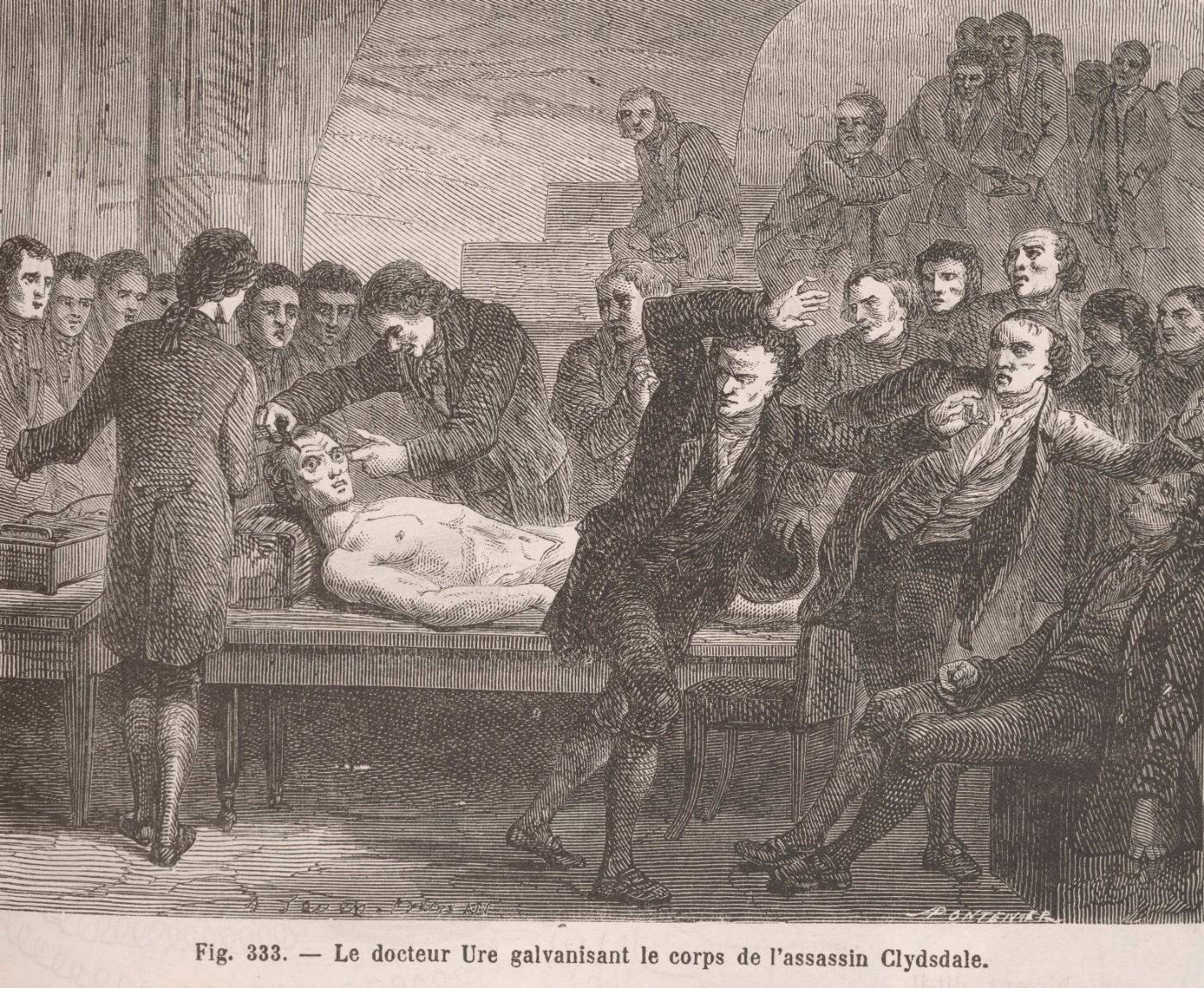

Frankenstein; or, The Modern Prometheus was published in 1818, written by Mary Wollstonecraft Shelley when she was only 18. Considered the first science fiction novel, her tale introduces two now iconic characters: the mad scientist, and his Creature, who is at once his greatest accomplishment and worst enemy. Dr. Victor Frankenstein eschews ethics, and through unorthodox experiments, brings to life an ungodly Creature. Upon its animation, Frankenstein rejects his creature as a hideous monstrosity. The Creature flees, and the doctor realizes his mistake, as the monster wreaks havoc and Frankenstein spends the rest of his days pursuing and trying to regain control of his creation. Though violent, the Creature longs to be understood, and even loved, making him a symbol for misunderstood outsiders everywhere.