After six decades in the art world, Judy Chicago is finally getting her due. Her exhibition “Herstory,” currently on view at the New Museum, is the artist’s first comprehensive survey exhibition in New York.

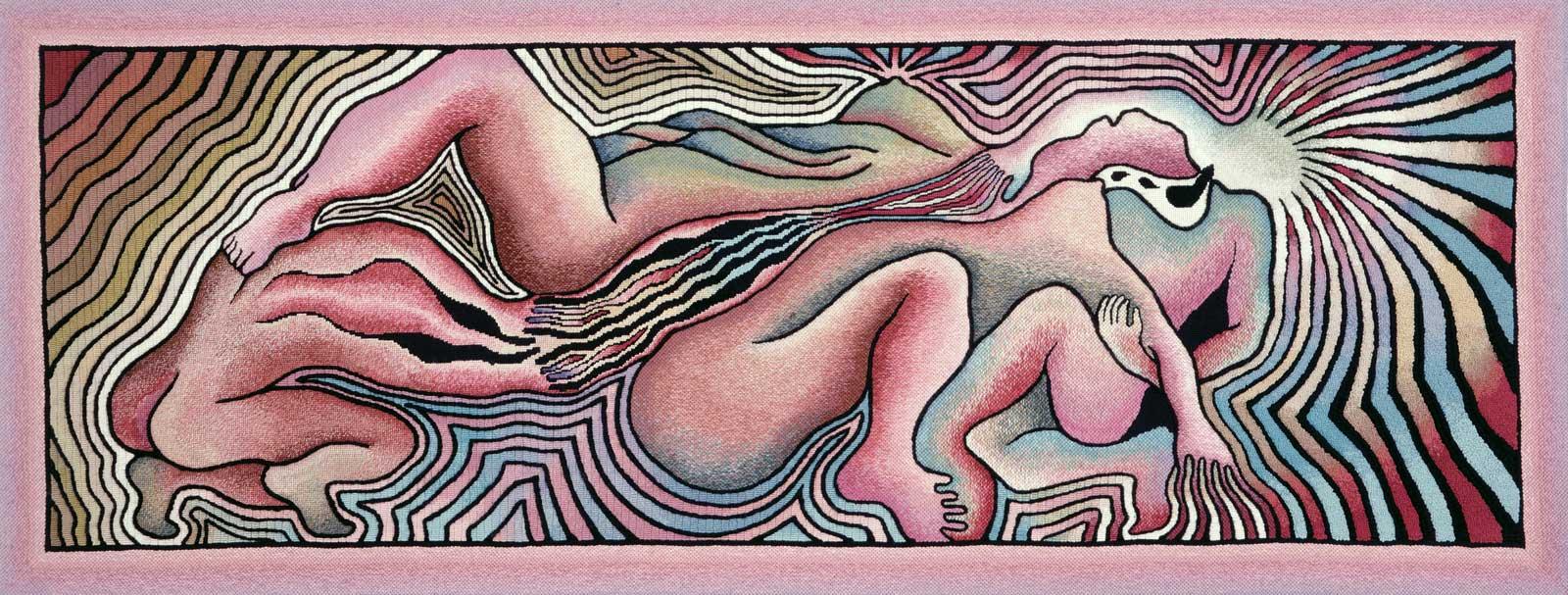

Organized by the New Museum's ambitious curatorial team including Artistic Director Massimiliano Gioni, Gary Carrion-Murayari, Margot Norton (who is also Chief Curator at the Berkeley Art Museum and Pacific Archive in California), and Assistant Curator Madeline Weisburg, the show, which has been extended through March 3, 2024, is a survey of Chicago’s work throughout various stages of her career. Ranging from the 1960s to a present day ongoing conversational project, the show looks at the role of feminism through the eyes of female and gender non-conforming artists who have largely gone under-recognized throughout the years. Intimately exploring Chicago’s oeuvre, the New Museum also houses an exhibition within an exhibition titled, “The City of Ladies” and features eighty artists ranging from the late Renaissance’s Artemisia Gentileschi, to Sojourner Truth, Dora Maar, and Leonora Carrington.

“We came to the idea of the ‘show within the show,’ this temporary ‘personal museum’ which Judy called 'The City of Ladies,'" Gioni told Art & Object. "It was a demonstration of her commitment to women's history and also a demonstration of the work she has done for decades to expand and enrich the art historical canon.”

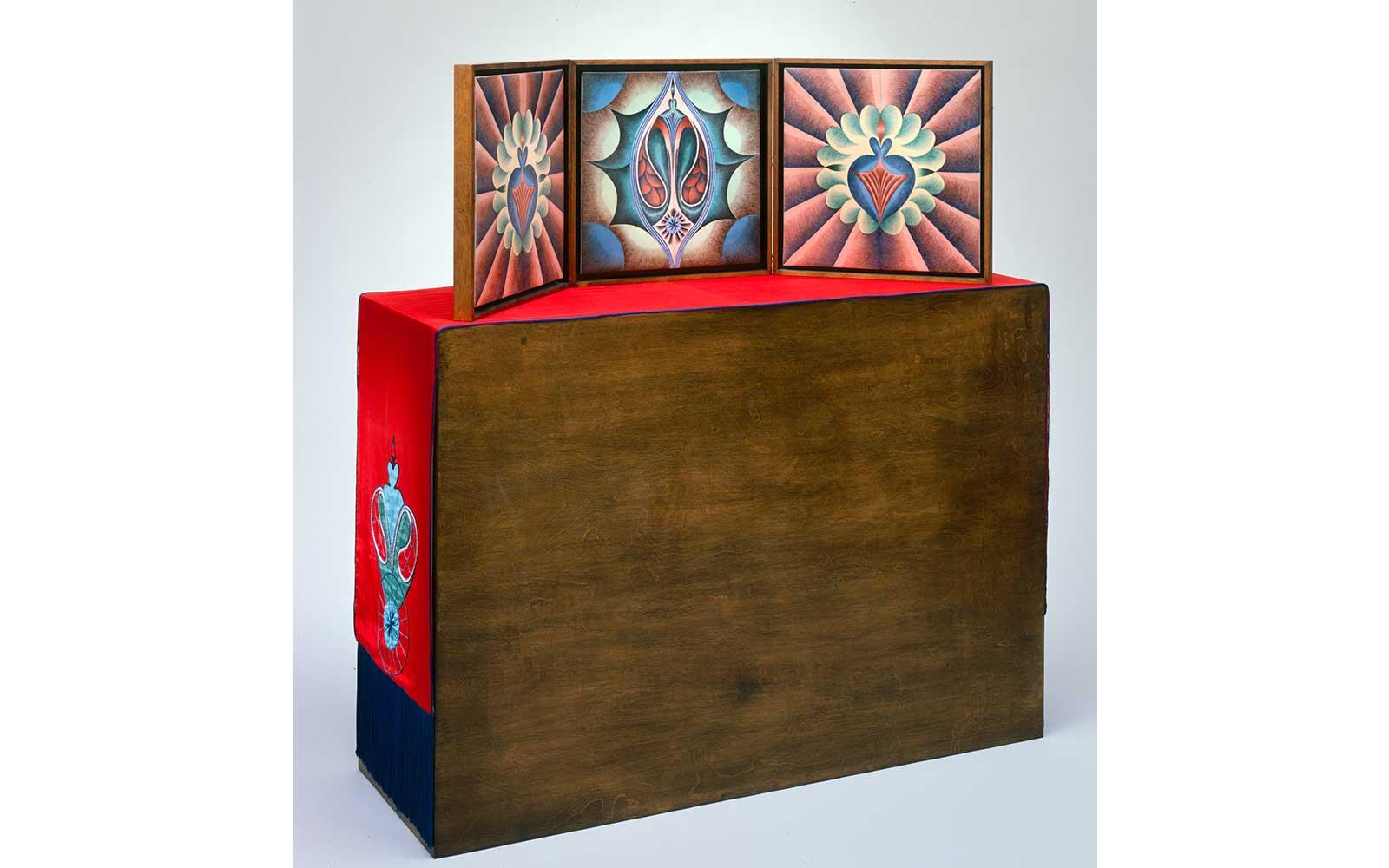

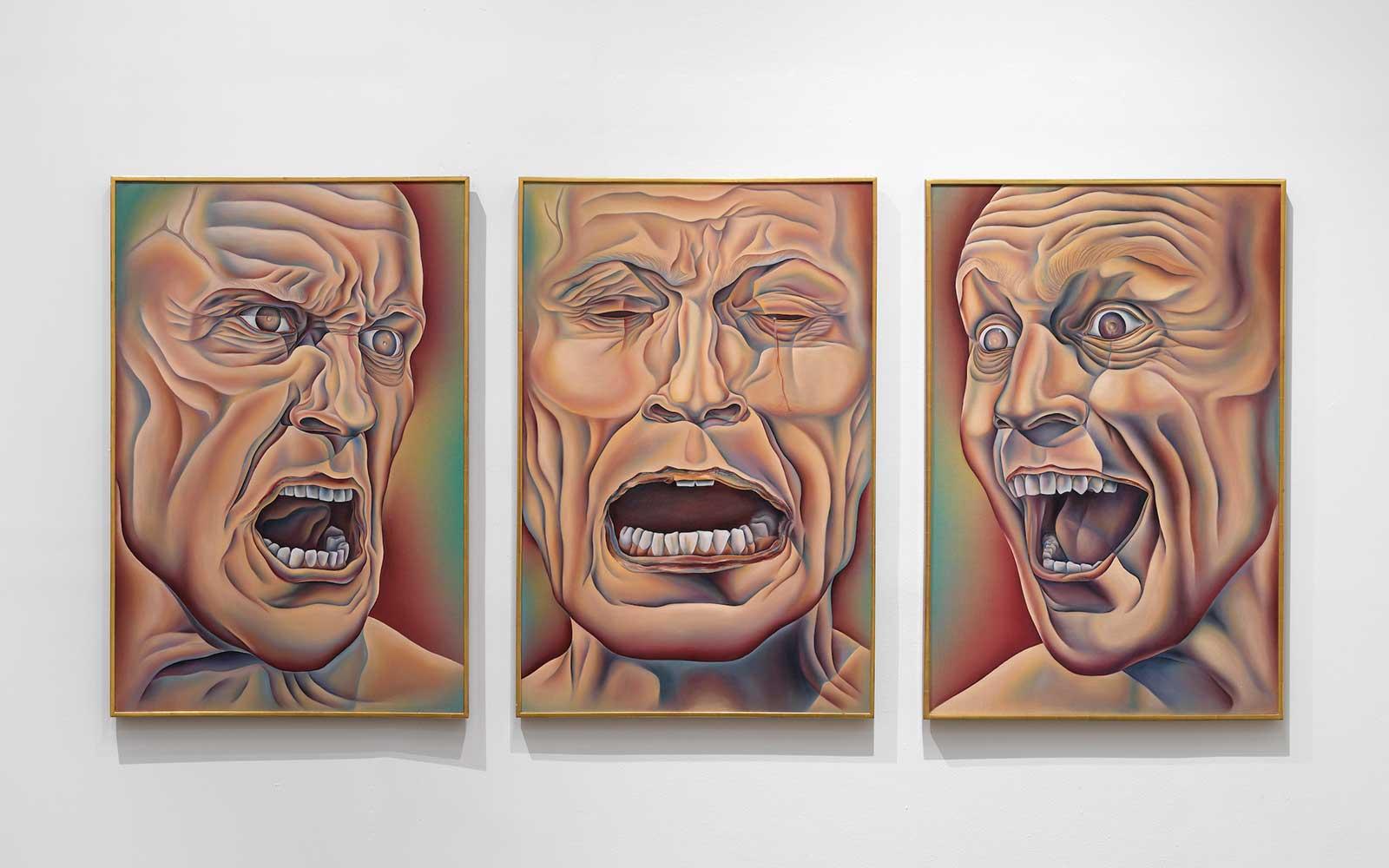

Judy Chicago, “Herstory” vibrantly expands and reignites a much-needed conversation around the artist’s work and her career of six decades. Her permanent installation at the Brooklyn Museum, The Dinner Party (1974-79), has left a qualifying mark on many New Yorkers and tourists alike over the years, and has kept her name fresh on the lips of those who visit. What the New Museum has done is build on that installation, expanding her New York presence by revealing not only the specific process that led to the ceramic ‘portraits’ of The Dinner Party but also shining a light on the elaborate metaphorical movement of her practice.