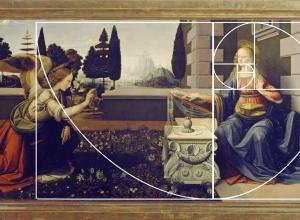

Samuel Scott, Wager's Action off Cartegena, 28 May 1708, oil on canvas, before 1772, National Maritime Museum

The 18th-century cargo vessel, the San José, sank off the coast of Cartegena, Colombia in 1708. But this “Holy Grail of Shipwrecks" might soon breach the surface again. Colombia’s president, Gustavo Petro, has made the recovery of the ship a priority for his administration, according to a Bloomberg interview with Minister of Culture, Juan David Correa, who said, “The president has told us to pick up the pace.” The shipwreck was laden with gold, silver, and emeralds, a treasure believed to be worth up to $20 billion.

The San José was one of three Spanish ships that were attacked by the British during the War of Spanish Succession (1701-1714). The battle, known as Wager’s Action, ended with a British victory over the Spanish fleet. As the British attacked the San José, the ship blew up and sunk. It went to the bottom of the sea with almost its entire crew and its coveted treasure. The ship was believed to hold 200 tons of gold, jewels, and other goods.

For the past few decades, there has been controversy over who has located the shipwreck and who has the right to receive the treasures. In 1981, a group of U.S. investors called Glocca Mora Co. working under the name “Sea Search Armada” (SSA), said that they located the shipwreck and gave the coordinates to the Colombian authorities in a deal in which they would receive half the treasure upon retrieval. In 2007, SSA sued the Colombian government to stop their excavation, and the Colombian Supreme Court upheld a ruling that SSA was entitled to fifty percent of the treasure.

In 2015, the Colombian government instead claimed that they found the ship at different coordinates, independent of the SSA’s search. Now, SSA is suing Colombia for $10 billion, which they believe is equal to half the fortune. In a quote to the New York Times, SSA’s lawyer, Rahim Moloo said, that if Colombia “wants to keep everything on the San José for itself, it can do so, but it has to compensate our clients for having found it in the first place.”

Spain also believes that the treasures belong to them, citing a UNESCO convention – because the ship belonged to the Spanish navy and the remains of Spanish sailors lie in the wreckage. The indigenous Qhara Qhara community in Spain, Colombia, and Bolivia also believe that the ship’s hidden treasures should be theirs, as the Spanish forced their ancestors to mine for the metals that were aboard the ship.

But at the same time, there are others who argue that the shipwreck should be left where it is, citing archeological best practices. Ricardo Borrero, a nautical archaeologist in Bogotá said in a quote to the New York Times, “The shipwreck lies there because it has reached equilibrium with the environment. Materials have been under these conditions for 300 years and there is no better way for them to be resting.” It would also be a feat to get the treasure back above water, given that the shipwreck is so deep and would require underwater submersibles or robotics to retrieve it.