Unknown, Headdress Ornament, 1st–7th century. Made in Colombia, Calima (Yotoco). Gold. 8 1/2 × 11 1/2 ×1 1/4 in. (21.6 × 29.2 × 3.2 cm). The Met. Gift and Bequest of Alice K. Bache, 1966, 1977. 66.196.24.

With the solar eclipse expected on April 8, 2024, we're feeling the importance of the sun and its impact on our lives. The power and prevalence of the sun as a theme and symbol throughout human and art history is undeniable. From the Virgin Mary’s biblical association with Solar bodies (both sun and moon) to the Incan sun god Inti to an eventual blending of the two that can be seen to this day across South and Central America, the evidence is clear. Though it would be impossible to offer a real survey of sun symbolism across time in one space, here is a quick look at symbolic traditions that this author finds most intriguing.

Unknown, Seated goddess with a child, ca. 14th–13th century B.C. The Hittite Empire, Turkey. Gold. 1 11/16 × 11/16 × 3/4 in. (4.3 × 1.7 × 1.9 cm)

This most likely depicts a major figure of Hittite divinity, the sun goddess Arinna. Symbols are used to communicate this—most notably, a disk-like headdress.

Unknown, Chariot of Triumph, 1717. Silk and wool. 267.3 x 346.7 cm.

In this tapestry, one can easily see King Louis XIV’s (known as the Sun King) most iconic royal heraldic symbol. The ruler used the sun as his personal symbol to emphasize his divine right and position himself as the center of the nation—just as the sun is at the center of our solar system.

Most likely made by Bonaventure Ravoisie (French, Paris, recorded 1678–1709), Partisan Carried by the Bodyguard of Louis XIV (1638–1715, reigned from 1643), ca. 1678–1709. Steel, gold, wood, textile, brass.

This partisan is one of three belonging to Louis XIV that now reside in the Met’s collection. This remarkable artwork exemplifies the prolific use of such iconography under the Sun King’s rule.

Another of these partisans additionally features a reference to the sun in Greek mythology, something Louis XIV held a deep fascination for. On that partisan, the sun god Apollo is shown being crowned with laurel by Fame.

Unknown, Headdress Ornament, 1st–7th century. Made in Colombia, Calima (Yotoco). Gold. 8 1/2 × 11 1/2 ×1 1/4 in. (21.6 × 29.2 × 3.2 cm).

As alluded to in the beginning, the evolution of the sun as a symbol within the Spanish colonies is a testament to the resiliency of communities and the importance of culture. For many of the diverse pre-Columbian societies, the sun held important cultural significance. The Camila peoples of modern-day Colombia, for example, produced shimmering, golden items like this headdress to be worn by their most elite figures. “Dressed in full regalia, Calima elites would have shone brightly, channeling the sun’s divinity and force as a source of life and renewal.”

Unknown, Plaque with the Crucifixion, ca. 1150–75. Made in Meuse Valley, Netherlands. Champlevé and cloisonné enamel, copper alloy, gilt. 4 x 4 x 1/8 in. (10.2 x 10.2 x 0.3 cm).

The sun was also an important symbolic detail in much of Christian European artwork.

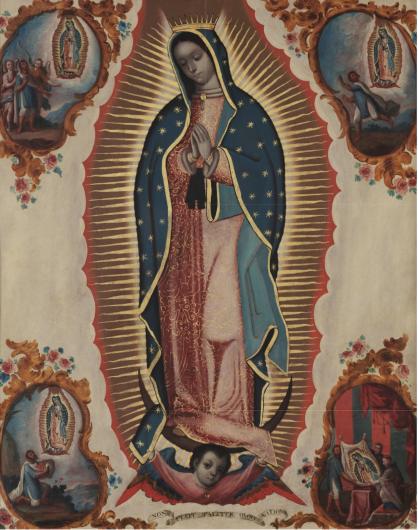

Sebastián Zalcedo, Lady of Guadalupe, ca. 1780. Oil and copper plate. 68.4 x 54.8 cm.

Though its connection to God and his own son is well established, the sun is also frequently connected to the Virgin Mary, especially in visual art. Interestingly, these visual manifestations have root in some biblical text. The recent LACMA publication Archive of the World suggests the classic Virgin of Guadalupe format was, “Inspired by the apocalyptic woman in Saint John’s vision of a ‘woman clothed with the sun, with the moon under her feet, and on her head a crown of twelve stars’ (Revelation 12:1).”

Unknown, Monstrance, 1667 - 1700. Peru.

Within the Spanish colonies, production of the monstrance—a ceremonial and elaborate tool used to hold the eucharist in Catholic worship—became very common. In Peru, one of the most common shapes was called the “sunburst.” The solar design of such objects in this region is undeniable. Even more remarkable, “the central top piece is called the “sol (the sun-shaped section designed to contain the consecrated host) is surrounded by a circle of rays, topped with knobs and finials.”

Anonymous, Defense of the Eucharist with Saint Rose, 1700/1750. Oil on canvas.

Though colonial powers attempted to feature the monstrance in paintings alongside the Spanish King and faithful, indigenous subjects to reinforce the idea of a divinely sanctioned rule, this was likely not always effective. It would be hard for peoples of Incan heritage to ignore associations with Inti, their ancient sun god. Images like this became remarkably popular and, although it is impossible to know for sure, Archive of Our World suggests that “images such as this likely took root precisely because of their potential to signify multiple things concurrently.”

Unknown, Seated goddess with a child, ca. 14th–13th century B.C. The Hittite Empire, Turkey. Gold. 1 11/16 × 11/16 × 3/4 in. (4.3 × 1.7 × 1.9 cm)

This most likely depicts a major figure of Hittite divinity, the sun goddess Arinna. Symbols are used to communicate this—most notably, a disk-like headdress.

Unknown, Chariot of Triumph, 1717. Silk and wool. 267.3 x 346.7 cm.

In this tapestry, one can easily see King Louis XIV’s (known as the Sun King) most iconic royal heraldic symbol. The ruler used the sun as his personal symbol to emphasize his divine right and position himself as the center of the nation—just as the sun is at the center of our solar system.

Ivy Pratt

Ivy Pratt is a regular contributor to Art & Object.