"The Bauhaus is considered one of the birthplaces of Modern Art and design, and on the centenary of its founding we are delighted to celebrate its genesis, the art that was created there and the influence it has had on generations of artists, designers and architects. We are particularly excited to be offering a spectacular Kandinsky painting from the period, alongside an important work by Oskar Schlemmer, which are very rarely seen at auction."

WASSILY KANDINSKY

“Every work of art comes into being in the same way as the cosmos – by means of catastrophes, which ultimately create out of the cacophony of the various instruments that symphony we call the music of spheres. The creation of the work of art is the creation of the world.”

Painted in February 1928 while Kandinsky was teaching at the Bauhaus in Dessau, this meditation on the essential beauty of circles embodies the aesthetic principles that he promoted to his students. Circles dominated Kandinsky’s most meaningful compositions of this intellectually sophisticated period of his career, and he expounded upon their incomparable aesthetic values in his writings. In this composition, the circles appear to be floating in space, like stars eclipsing and colliding with one another in their perpetual motion through the cosmos. When the school moved to Dessau, having been closed by the National Socialists in Weimar, Gropius designed a housing estate for the Bauhaus masters. Once Kandinsky completed this work, he hung it in the exotically colored living room in the Masters’ House that he shared with Klee–set against walls painted gold, pale pink and ivory. The painting’s first owner was businessman and collector Otto Ralfs, who went bankrupt in 1930s and sold it to Salomon Hale, a private collector of Polish origin, based in Mexico City. This was organized with the assistance of Mexican muralist Diego Rivera, who had wanted to purchase it for himself but was sadly unable to afford it.

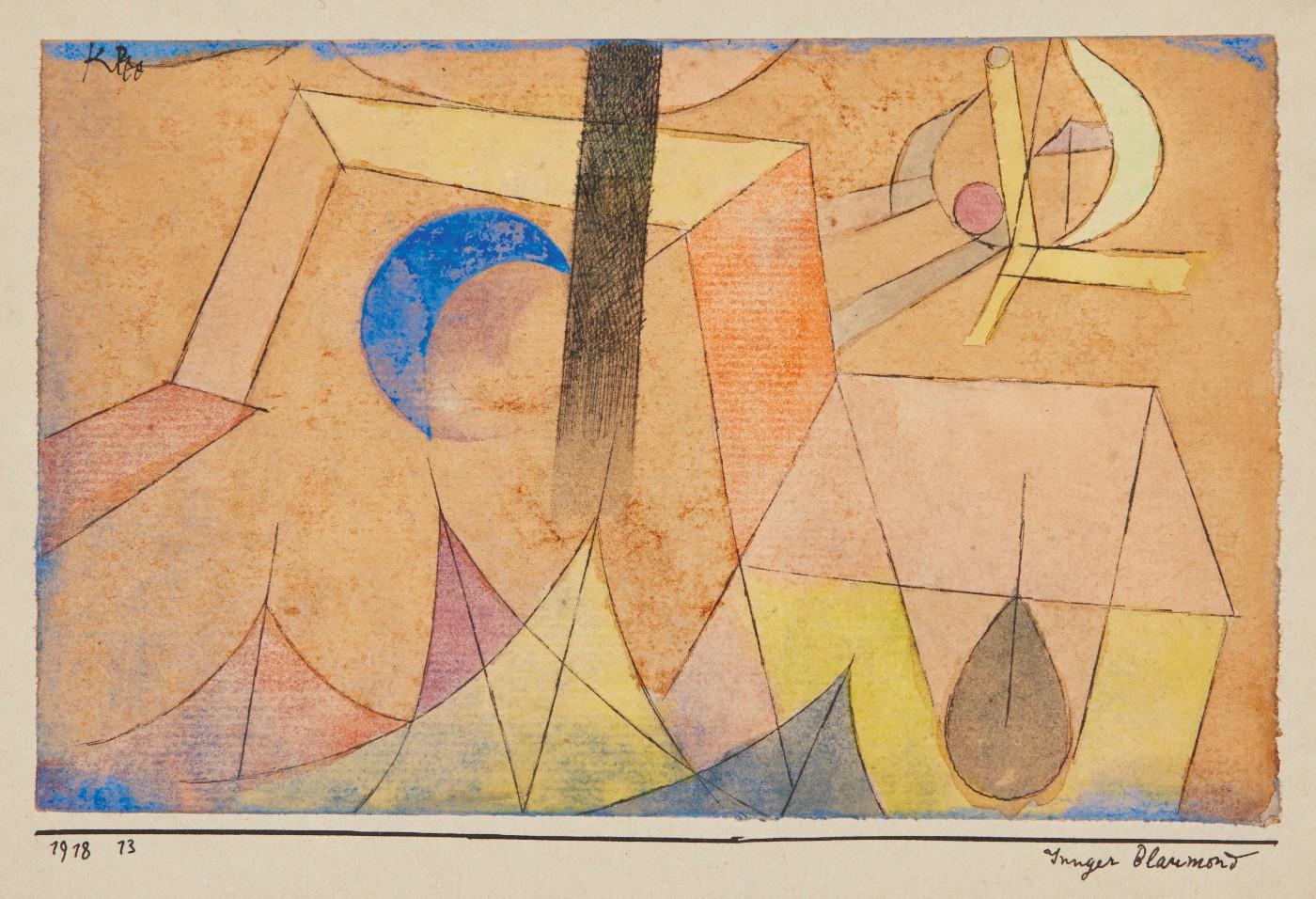

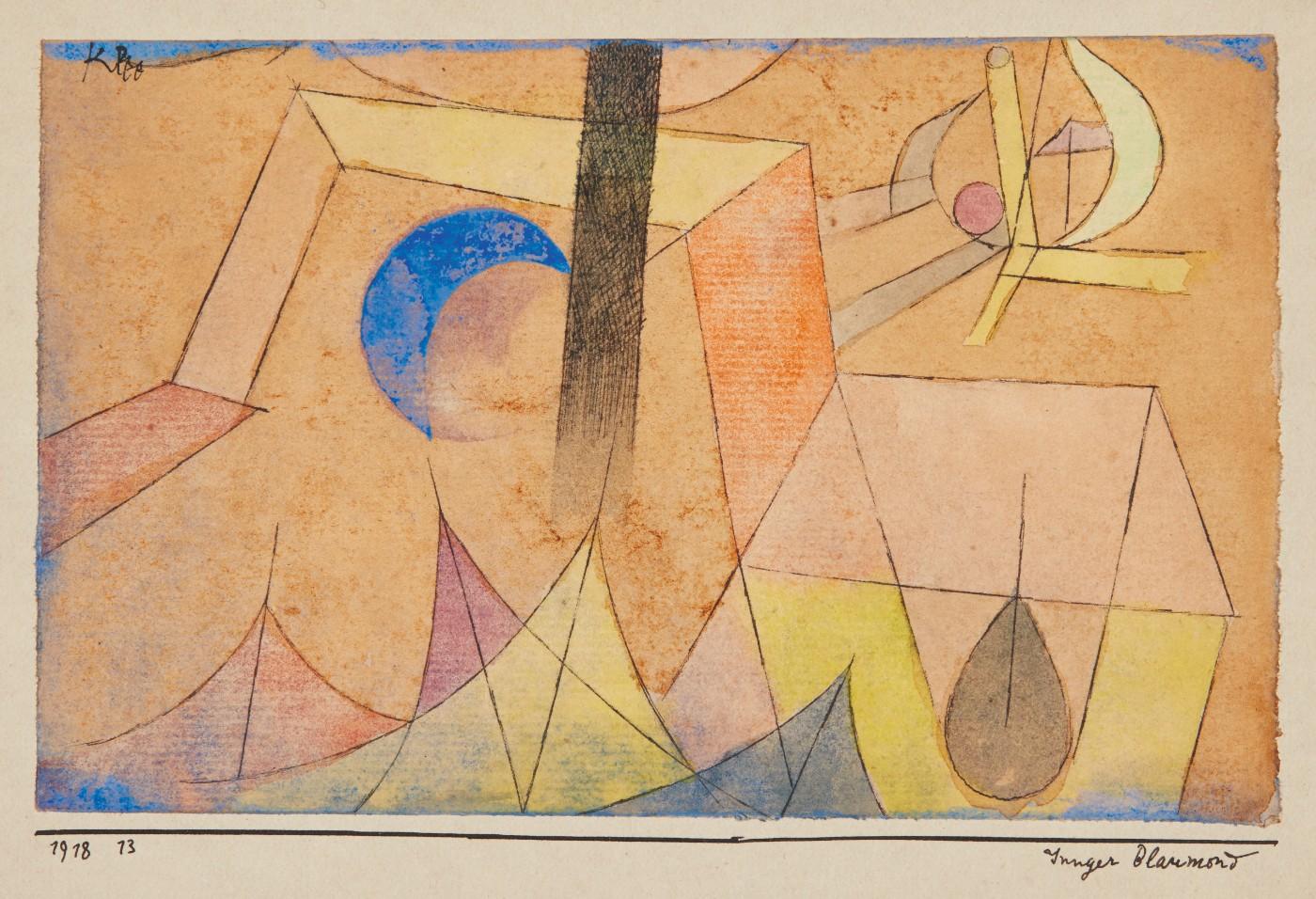

Wassily Kandinsky, Sans titre, watercolor and ink on paper, 1941 (est. £450,000-550,000)

Painted in Paris in 1941, this wonderfully playful and optimistic work on paper belongs to the last great period of abstraction in Kandinsky’s art. Drawing on the severe geometric construction which characterized the works of his final Bauhaus years, in Paris he superimposed a repertoire of stylised and biomorphic shapes that seem to have been borrowed from the realm of molecular biology (first explorations into which were occurring at the same moment). Here, a variety of forms–both geometric and organic–are scattered across the surface of the paper, set against a neutral monochrome background.